Your surgery is expensive, but we still do it for free

The financial crisis is driving the popularity of informative invoices. But does such information make the public appreciate public services any more?

T oday you've been discharged after your health problem has been treated in this center. We hope that you've received a high-quality healthcare service and have felt comfortable during your stay."

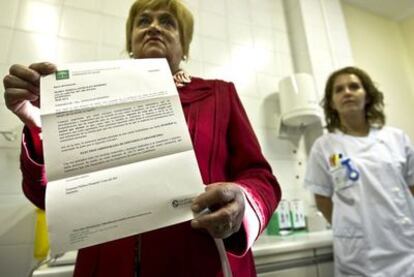

This, give or take a few words, depending on the hospital, is the opening of the letter that patients from most Andalusian hospitals have been receiving in the last year after undergoing surgery for anything from cataracts, to hernias or gall bladder problems.

But the true objective of the letter can be found in the next paragraph: "We think it's important for you to know, for informative purposes only, that the procedures and treatments that you have received at this facility, as well as the hospitalization time required for your recovery, entail a cost that you shall not, under any circumstance, have to pay since, as you know, healthcare in Andalusia is financed by all of our taxes." After that, the amount that the care provided actually cost is given.

This is the so-called "informative invoice," a practice which, fueled by the crisis, has spread in recent months to public health services in various regions (in Spain, each region administers its own healthcare).

There is no study that shows that these invoices do any good, so why is there such an interest in using them? According to those in charge of this initiative, the answer is that the cost is "almost zero." And, if nothing else, it helps improve the image of public services.

Based on this argument, the Andalusian government, which has been giving its patients informative invoices for different healthcare procedures since October 2010, has just passed a measure to roll them out to 16 other public services, from legal counsel and school transportation, to home help. The goal, according to the regional politician Mar Moreno, who has coordinated the project, is to "inform and raise awareness."

"The best way to defend public policies is for citizens to value them. And in order for that to happen, it's essential for them to know how much they cost; to know where their taxes are going," says Moreno.

The perception that people are not fully aware of the price of services is not shared by everyone approached for this report, but one thing is for sure: on November 29, the same day that the Andalusian government passed its informative invoice program, the Center for Sociological Research (CIS) released its latest survey on public opinion and fiscal policy. The findings support the theory that public services need an image makeover. According to the study, 54.5 percent of all Spaniards think that they pay a lot of tax, while 59.1 percent think that they get less from the regional governments than they give.

In the first phase of the Andalusian program, which has been dubbed FIJATE (an acronym for "Informative Invoice from the Region of Andalusia. Effective transparency" - fíjate also means "pay attention" in Spanish), 16 services have been added. The Andalusian government estimates that it will send out a total of 4,000 such letters a year for a total of five billion euros in services rendered.

Moreno insists that the objectives of the measure do not include saving money by dissuading people from going to the doctor or requesting home help, but to make them aware that such services are expensive and, as such, they should be used responsibly.

When she presented the measure for public hospitals, the Andalusian healthcare chief, María Jesús Montero, referred to the need to promote a rational use of services. "Just because they're free doesn't mean they can be used indiscriminately without realizing that they are a valuable asset," she said. But a year after the implementation of these invoices, there is still no study that shows that, if people do in fact go to the doctor more than necessary, they think twice when made aware of the cost of these visits.

This is one of the main criticisms leveled by detractors of these informative bills. "The problem is that their effectiveness hasn't been assessed. As a citizen, I'm fine with knowing where my taxes go. But I imagine that they also intend to make people use resources better, and that has never been evaluated," says Juan Oliva, president of the Association for the Economy of Health (AES) and a board member of the Spanish Society for Public Health and Health Administration (SESPAS).

Oliva is among those who think that these programs reek of propaganda. And he's not the only one: "It's one of those things that become popular and can't be stopped, even though we get the feeling that they're worthless," says Marciano Sánchez Bayle, a doctor and spokesperson for the Federation of Associations for the Defense of Public Healthcare. For him, these bills aren't even worth it for the information that they might give people. "The vast majority of people in this country are aware that healthcare is financed with taxes, and they know what taxes they pay. If the goal is to inform about their cost, they could put them online, or on a bulletin board in the clinic," says Sánchez Bayle, who thinks it's a mistake to spend money on such measures. As food for thought, he cites the following data: in the United States, where bills are given out for everything, administration and management take up approximately 30 percent of all healthcare costs. In Spain, it only represents just seven percent of the budget. "If you use up resources on one thing, you don't have them for another. We've got to make sure that the measure doesn't have more costs than benefits," says Sánchez Bayle.

But the public leaders behind these invoices insist that the cost of issuing them is "minimal." The Andalusian program FIJATE doesn't have its own budget, and the various departments must find a way to pay for it. Between October 2010 and September 31 of this year, 19,189 invoices were issued, totaling 19.5 million euros. But for the Andalusian healthcare service, the cost of issuing these bills is "almost zero" says Celia Gómez, director of healthcare planning and innovation for the region of Andalusia. "Paper, ink and lots of enthusiasm from the professionals. When it was implemented, the fact that it wouldn't cost much was valued a great deal, because money is scarce," she says.

Gómez insists that the first goal of the bill is to "inform citizens of the cost of services and emphasize their value," although as a secondary goal, he admits that this knowledge "helps people use services better." But how can it help citizens? Because one thing is clear: in the case of healthcare, the only decision the user makes is whether or not to go to the doctor. Apart from that, it's the healthcare professional who decides if the patient needs a certain operation, test or treatment. "Maybe we doctors are the ones who should know what the tests we order cost, but I don't think it makes much sense for the patient to be told. Is your attitude going to change because you know that an x-ray costs a certain amount? Not one bit," says Bayle.

The region of Andalusia is currently assessing the effects of the measure in two of the first hospitals where the invoices were handed out: in Marbella (Málaga province) and Pozoblanco (Córdoba). The study is not finished yet, but according to the director of planning and innovation, the indicators are "good" and there is no sign that patients reject it in any way.

The Andalusian government has made a point of not sending the invoices by post or email, but rather handing them out in person, in order to humanize the process and be able to gauge people's reactions. "Most of them express satisfaction. It's very important not to interpret it as if the patient were being blamed, as if we were saying, 'Look how much you've cost us'," says Gómez.

José Martín, chair of the economics department at the University of Granada and an associate professor at the Andalusian School of Public Health, thinks that patients' reaction is likely to be: "And what exactly are you trying to tell me here?" "But that in itself shows that we've got a problem," he says. "People have got to know how much things cost." Martín is a staunch supporter of the measure because he thinks that it does, in fact, fulfill the objective of raising awareness about the cost of services. "The informative invoice is not a miracle that solves the problem of healthcare management, but I think it's headed in the right direction."

Luis Ángel Hierro, a professor of public economics and president of the Economic and Social Council of Seville, is also more in favor than against the measure. He often reminds his students that they pay just 15 percent of the real cost of a year of university. "Taxes such as VAT and income tax are more visible. What is not visible is the cost of services. Everyone knows how much their water or electricity bill is, but not public lighting, schools or the police. From that standpoint, it's useful." But Hierro is skeptical that these invoices promote a more rational use of services. "I just don't believe it. It's not going to have that effect," he says.

The future recipients of the invoices that the Andalusian government is going to issue are generally receptive to the measure, although some are more wary than others. Francisco Mora Sánchez, president of CODAPA, the Andalusian confederation of parents in favor of public education, says that he will gladly accept any information he receives as a user of these services. As for education, the regional government plans to give the details of the cost of school transportation and the laptop computers that are given out in some classrooms. "I think that it may help families value the services they receive more," he says. Manuel Gómez, who represents CADUS (the University of Seville's Student Council) doesn't have a problem with being told how much his schooling costs, but he is somewhat afraid that putting a price on his education will be used "to justify a progressive rise in taxes," especially on second- and third-time university enrollments. "The message that we students are irresponsible, and that taxes have got to be raised, has already taken root. I hope that this isn't used to justify it."

The dean of the University of Cordoba, Antonio Cubero, also thinks that it is "interesting" for people to know the prices of services. "The way that this expense is expressed, and according to what parameters, is an entirely different story. We still don't know how it's going to be quantified," he says. This lack of information is also the main criticism from the consumers' federation FACUA. "We would have liked it if we users could have a say as to when we are informed and the content of the message that is conveyed to people. Other than that, we think it's positive," says Olga Ruiz, president of FACUA's Andalusian division.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.