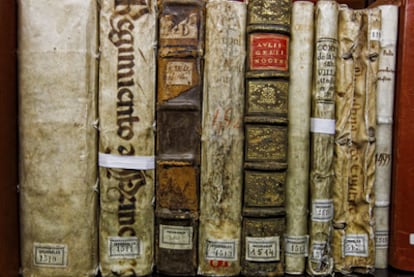

Three centuries on the shelves

Spain's National Library faces uncertain future and the gigantic challenge of digitalizing its collection

Three centuries lie between the 6,000 volumes that King Philip V brought from France in 1711 - decreeing they would be maintained by taxes on "tobacco and gambling" in the kingdom - and the 110,000 people currently listed as friends on the National Library of Spain's Facebook page. They have been three centuries of adapting to changing times for an institution that, to this day, aspires to house all the knowledge in the world, despite the implosion of the "Gutenberg Galaxy," or perhaps, because of it. Exhibits of Leonardo's codices, book shows, musical recitals, commemorative stamps, Hispanist conferences and Cervantes Award winners meetings will fill 12 months of tricentennial celebrations (at a cost of some 1.65 million euros) for a mammoth institution that is now at a virtual crossroads.

Though a commemoration is a celebration of the past, it also invites questions about the future. In the case of the National Library, the main question is if in 50 years (let alone another three centuries), there will be anyone who cares about preserving the 22 million documents currently housed between the old dinosaur on Recoletos Boulevard and the far more modern facility in Alcalá de Henares, (where 65 percent of the budget is destined). What's more, which documents are worth saving? Only the incunables? Or also the ancient books, the just plain old ones and the recently published ones? And what about the albums and DVDs?

At a meeting of the commemoration committee, scientist Margarita Salas, president of the Library board, said that preservation is now more important than ever. There is, of course, one word that answers all questions - digitalization. Over the last decade, it has become essential for this institution, which receives 20 tons of paper each month and nearly 900,000 new documents each year.

So far, the National Library has scanned roughly 53,000 documents, beginning with the most valuable ones. They can now be accessed through the Hispanic Digital Library program on the Library's website. Though it may seem insignificant given the dizzying amount of data archived on shelves that cover some 500,000 meters of floor space, Library Director Glòria Pérez-Salmerón believes "it is a good start." Not all documents "deserve to be digitalized," she adds, using the word document to cover everything from a work by Beatus of Liébana to one of Benito Pérez Galdós' National Episodes to a VHS recording of a production by Spanish theater company Animalario.

"We are on the path to becoming a hybrid library, in which two realities co-exist. The new ways do not necessarily mean the death of the more traditional ones," says Darío Villanueva, a Library board member and director of the Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library's scientific council. "In a future where physical libraries will tend to disappear, a large library that houses public documents makes more sense than ever."

As coordinator for the special commemorative book, Villanueva submerged himself in the past three centuries of transformation for the library. This historical look back is made somewhat more digestible in a shorter "reader's version" by Andrés Trapiellor, who says it is "a celebration of books during paper's swan song."

It is an action-packed tale full of changes like that in 1836 when the Royal Library became the National Library, and as such, the selfless guardian of Spanish cultural heritage (even today, a copy of all published books ends up here). And of wars, of course, such as that of 1936, which caused the closure of the center, and left physical scars. That year, the head of the Lope de Vega statue tumbled off after a bombing, funds were moved to the basement and 99 boxes with the most valuable treasures were evacuated to Valencia.

Today, the Library, destined like Atlas to keep walking despite carrying the weight of the world on its shoulders, is facing the future on a yearly budget of 42.7 million euros, a sum four times smaller than that of the Library of Congress in Washington. Added to this stubborn reality is the recent decision to lower the Library's classification for economic reasons - from directorate under the Culture Ministry to sub-directorate. In May of 2010, this caused the irate resignation of former director Milagros del Corral, who lamented seeing the National Library "on the list of the 32 most useless directorates." Not the most auspicious omen for such a big birthday.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.