A writer's preserve

The family of author Miguel Delibes is working to ensure his literary legend lives on

A year and a half after his death, Miguel Delibes' desk inside his Valladolid apartment remains exactly the way he left it. On it are the trembling first lines of an interrupted letter and the abundant notes he made in cramped handwriting in a notebook labeled simply "La artritis" (Arthritis). For a while, the author of some of the most acclaimed novels in Spanish literature, such as Five Hours with Mario and The Innocent Saints, kept busy working on what was going to be Diario de un enfermo de artritis reumatoide (or, Diary of a rheumatoid arthritis patient).

But beyond those notes, did one of Spain's best contemporary writers leave any unpublished novels behind? "Fundamentally, no," says his daughter Elisa. "We found an article he was writing about [the painter] Antonio López and we sent it to him. It was meant for him."

Elisa Delibes says her father "knew how to look at paintings," and the eighth-floor apartment in which he lived provides good testimony of that. The monk-like bed where he died on March 12, 2010 is presided by an autographed drawing by Gregorio Prieto depicting an old man who looks like Walt Whitman, while behind the table he inherited from his parents there is a famous painting in which García Benito portrayed Ángeles, Delibes' wife, who died in 1974. The writer was never the same after that. Everyone in the house refers to her as "the lady in red," because of the novel Delibes published in 1991, Señora de rojo sobre fondo gris (or, Lady in red against a grey background).

The writer's seven children are planning for his untouched desk and the adjoining room, where he used to read and listen to music, to be transferred exactly the way they are to the future headquarters of the new Miguel Delibes Foundation. The board of trustees met for the first time last week, and the organization was symbolically blessed on Monday in an event presided by Crown Prince Felipe and his wife Letizia. That is the day Delibes would have turned 91 years old.

Alfonso León, the managing director of the foundation, explains that Delibes' written legacy, ceded free of charge by his family, will be slowly taken to the Casa Revilla in Valladolid after it is inventoried. The foundation's architectural neighbors will be the José Zorrilla Museum, the National Museum of Sculpture and San Pablo square, which houses a church and the former royal palace, one of the settings for The Heretic, the novel with which Delibes said goodbye to fiction in 1998. His desk and reading room, however, will be taken to the future library of Castilla y León, which will bear his name and be located near the city's Campo Grande train station. Because of the economic crisis, the new facilities are not expected to open before 2018. When they do, visitors will be able to see the rooms where Delibes spent the last 30 years of his life. After his wife died, he wanted his new home to be "a lonely man's house," his daughter recalls. "Jot down my new address. With this change in homes, I am burying 25 years of my life," he wrote to Josep Vergés, his longtime publisher at Destino, in October 1980.

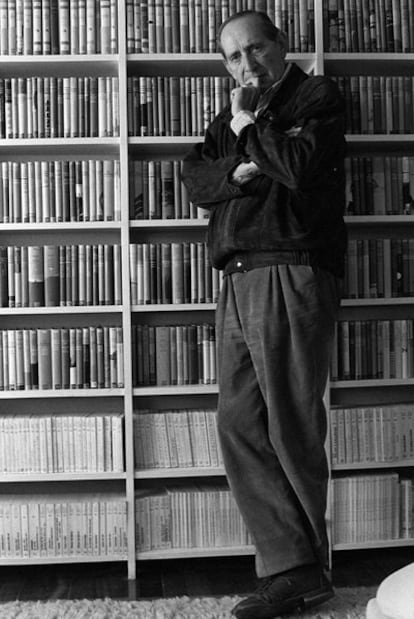

The writer took care of moving his books personally. Elisa Delibes still remembers her father taking boxes from the old place to the new one every day. "He would go out for a walk and bring a few books with him. He wanted to put them in order personally. Toward the end of his life, he hardly moved from here."

While the "most museum-like" items await the day when they will be transported to their new location, the foundation is already working away. León underscores the "plural and balanced" nature of a board of trustees made up of Delibes' children and personal friends such as Emilio de Palacios and Fernando Tejerina, as well as institutions such as the regional government of Castilla y León, the city of Valladolid, the provincial authority and the University of Valladolid. Also sitting on the board are private companies such as construction firm Collosa, the Iberdrola Foundation, the publisher Destino and the newspaper El Norte de Castilla, which Delibes once edited. The 305,000 euro budget for 2012 has been earmarked for the creation of a Delibes website and for its content to be adapted for mobile devices, with the goal of disseminating his work and conserving and digitalizing his legacy. Beyond the literary concerns, there will also be activities that underscore Delibes' personality, chiefly "his Christian humanism and his interest in ecology and popular culture," says León.

Although it doesn't seem it would be too difficult to disseminate the work of one of Spain's most prestigious and popular novelists, León notes the writer always lamented the deficient distribution of his books in Latin America. That is why the Brazilian Academy of Letters will devote this November 23 to Delibes, whose "intellectual biography" will be published by Destino next year. Its author, Ramón Buckley, insists that "if there is no other author as deeply rooted in a landscape and a language, there is also no other who has been able to move beyond them so well; that is why he is an author for the 21st century."

The legacy now in the foundation's custody is formidable, containing around 10,000 books that made up Delibes' personal library, spread between Valladolid, Sedano (Burgos) and Tordesillas. "I think he owned homes in order to have a place for his books," says his daughter ironically. "Except for a couple that he consulted as he was writing The Heretic, he never underlined them. He didn't like for them to get deteriorated. He would rather comment on them than make notes in them."

The writer's home is filled with what his daughter refers to as all-purpose rooms where his National Literature Prize diploma hangs side by side with the Golden Deer awarded by a hunter association or a medal given to him by a society of pediatricians. Once every item is catalogued, it will become part of the Delibes archive together with the two cornerstones of the legacy: the manuscripts and the letters. There are dozens of folders bearing classic titles ? El camino, Las ratas ? and containing thousands of handwritten sheets and filled with corrections. This feast for philologists will never be complete, since Delibes only kept 30 manuscripts of his 50 or so books. "The rest he possibly gave away. Sometimes he talks about that in some of his diaries," explains Elisa Delibes. She says she does not recall eating sandwiches wrapped in original manuscripts, as some have alleged.

Delibes' correspondence is a chapter unto itself. No one yet knows how many items it contains. "Letters were his obsession, not hunting or fishing," says his daughter, thinking how excited her father would have been to see his face on a new 80-cent stamp released by the Spanish postal service. "He classified his stamps and forms, and he knew the mail pick-up times off by heart. He did not envy [Camilo José Cela] for winning the Nobel, but for being made honorary mailman."

Delibes kept most of the mail he received. Elisa remembers some that were especially meaningful to him, such as the one written by author Ignacio Agustí saying that "no matter what happened," his favorite to win the Nadal Prize in 1947 was La sombra del ciprés es alargada (The shadow of the cypress is long): "It's been said that without that prize, he would not have kept on writing, but he told me that this letter would have been enough encouragement."

In 2002, Miguel Delibes grudgingly consented to the publication of his correspondence with Vergés, his publisher. It is the story of four decades of Spanish literature and publishing, including the book-by-book inside story of one of its greatest figures. It bears imagining the estimated value of his long correspondence with other major writers such as Ana María Matute, Carmen Laforet, Carmen Martín Gaite, Francisco Umbral and Manuel Leguineche. To walk around his house is to confirm that the "Delibes Galaxy" is full of planets we have barely begun to view through a telescope.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.