The last stand of General Franco

A final statue of the dictator was mothballed after the assassination of Admiral Carrero Blanco on the day he was due to inspect the artist's work

The snowy peak of Peñalara is reflected on a blue lake at the far end of the gardens of the Royal Palace of San Ildefonso, in La Granja de Segovia. Right on the northern tip of this placid body of water, there is an old building with wooden window frames and coffered ceilings known as Casa de la Góndola. In it, there is a ship built under Carlos II in the late 17th century, which the royals used to fight mock battles known as naumachies.

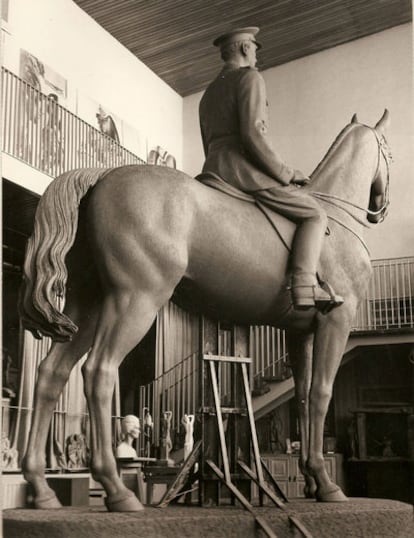

Next to this vessel, another relic from the more recent past languishes quietly: the last bronze equestrian statue of Francisco Franco ever made, and which the dictator did not live to see unveiled.

The sculpture was made in 1973 after Luis Carrero Blanco, then the prime minister, commissioned it from the Mérida-based artist Juan de Ávalos. It was meant to go up in Valle de los Caídos, the giant monument to the Civil War built by Franco and where the dictator's remains are buried, but an unexpected event cut the project short and ended this final ride to statuary glory.

"I saw him go white as he heard that the prime minister had been blown up"

The model was sold to a landowner; his granddaughters keep it as an heirloom

Early in the morning of December 20, 1973 the center of Madrid was teeming with activity. People in the know exchanged wary glances as police cars zoomed by and a large group of students and blue-collar workers lined up at the Justice Palace to witness a historical trial against leaders of the underground union Comisiones Obreras (CCOO), today one of Spain's two big labor organizations.

Meanwhile, in the elegant Salamanca neighborhood, inside the Jesuit church on Calle Serrano - across from the US Embassy, where Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had just been on a visit - Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco was attending mass. After the service, the prime minister was planning to visit Juan de Ávalos' workshop in northern Madrid and grant his final approval to the statue of the Generalísimo.

The mayor of Madrid and the architect Miguel Ángel García Lomas were already there by nine in the morning. The statue, which was meant to first go on display at the Royal Palace before its final installation at Valle de los Caídos, was a massive affair weighing nearly 10 tons. The pedestal featured the dictator's favorite emblems.

Everyone was waiting for Carrero Blanco's arrival to see what corrections and instructions he would issue, when Mayor García Lomas received an unexpected phone call.

"I watched him go white quite clearly: he had just been informed that the prime minister had been blown up along with his bodyguards inside his vehicle," remembers 61-year-old Luis Ávalos, the artist's son, who was then just 25.

"[My father] had chiseled two small scale models, one with a gold pedestal, worth around 800,000 pesetas (approximately 4,800 euros) at the time, that was to go to Franco, and another worth half a million pesetas (3,000 euros) that Carrero Blanco would keep as a memento," he recalls.

Following Carrero Blanco's assassination by ETA, the model that was to be his was sold to Enrique Coronado, a landowner whose granddaughters still keep it as a family heirloom. After Franco's own death, the statue embarked on an erratic journey that ended inside a corner of Casa de la Góndola.

Yet there is one more stop in store: the Historical Memory Law stipulates that such expressions of admiration for Franco will be kept in a museum in Salamanca now that they can no longer be displayed in public places such as squares and army barracks.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.