Engineers wanted: Mexico looks to join the global semiconductor race

The country is taking steps to make room for the next generation of professionals — but needs investment and stability in its relationship with the United States to capitalize on opportunity

In Guadalajara, the Mexican Silicon Valley — where 80% of the country’s semiconductor industry is concentrated — the most sought-after raw material isn’t silicon: it’s human talent. Mexico is betting on its proximity to the United States and its manufacturing tradition to become a key link in the integrated circuit value chain, currently dominated by Asia.

But this ambitious plan requires aligning the private and public sectors to modernize educational programs, create incentives, update legal frameworks, and attract investment to scale up the project. It also calls for close coordination with both diplomacy and industry on the other side of the northern border, at a time of high trade uncertainty.

“Mexico has all the necessary conditions when it comes to the quality of talent required for a highly competitive industry. What we are missing — and we are working on this — is the quantity of that talent. We have to be aggressively generating the largest number of specialists every year to be able to capitalize on this opportunity,” explains Rodrigo Jaramillo, CEO and co-founder of Circufy, a Mexican start-up that specializes in the advanced design of integrated circuits, speaking from the company’s Guadalajara offices.

Circufy has started to recruit engineers directly from universities, offering them “last mile” training at its facilities. “Some of them work with technologies that probably only exist in the hundreds, worldwide,” adds Jaramillo.

Even amid concerns over the Trump administration’s harsh criticism of the CHIPS Act, which was enacted by the president’s predecessor Joe Biden to drive manufacturing in the United States with help from the country’s allies such as Mexico, Panama and Costa Rica, Mexico has faith that its semiconductors “master plan” will be shielded from the vagaries of its primary trading partner. Recently, Intel and Qorvo announced the imminent closure of their plants in Costa Rica, in part due to Trump’s reluctance to move forward with Biden’s plan.

“We are looking for signs and incentives to the industry, like consistent dialogue with the United States which, despite the high-level disruptions that could take place, remains focused at the technical level,” says Diego Flores, head of the Mexican Ministry of the Economy’s semiconductor plan.

“Mexico has decided to get into the ATP segment of semiconductors [assembly, testing, and packaging] because of its integration with the United States, the development already present in the automotive and aerospace industries, and because it’s something U.S. fabs [semiconductor factories] will need. Given how advanced they are, they will stop doing certain processes, which will then have to be carried out here,” he adds.

The Mexican government began conversations in 2022 with the Semiconductor Industry Association — the coalition of 99% of the sector’s major companies, such as Samsung and Nvidia — and with the U.S. embassy in the hopes of developing and connecting the two counties through four large supply routes: from California to Oregon; from Arizona to Idaho, where Micron is expanding operations; from Ciudad Juárez to throughout the Midwest up to Ohio, where part of Intel’s production will be located; and lastly, from Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas to the Silicon Valley of Texas.

“We are identifying our potentialities based on where these factories are located, or where they will be located,” says Flores.

However, the official did not announce any new investments for 2025, emphasizing that they are maintaining ongoing talks with key companies in the sector. In October, Taiwan’s Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics assembler, said it is building a second factory in Guadalajara to manufacture Nvidia’s next-generation super-chips.

Joining the race

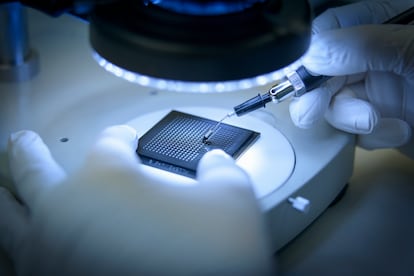

The manufacturing of semiconductors is divided into stages, beginning with research and development. Then comes design and manufacturing and finally, the process known as ATP, in which silicon semiconductors are assembled, tested and prepared for use in electronic devices. This last stage is precisely where Mexico wishes to insert itself.

There is further segmentation in the sector according to the size of transistors, which is measured in nanometers. One chip contains millions, or even billions, of diminutive transistors. Smaller and smaller transistors are needed to produce smaller but efficient chips, key to developing compact but powerful devices like those that can process artificial intelligence in a smartphone — a process dominated by industry leaders.

Mexico has identified an opportunity in manufacturing chips from older generations, meaning those greater than 30 nanometers that are typically found in switches, lighting and Mexico City subway doors.

For context, the Circufy design center, which is principally employed by businesses located in the San Francisco Bay Area as well as in Texas and Arizona, is focused on advanced technology below five nanometers, a highly specialized area that requires large injections of capital for research and training.

Like many countries, Mexico is facing a growing dearth of trained technicians, especially in areas like computing, robotics, nanotechnology and AI. According to a 2024 survey carried out by ManpowerGroup, a multinational that specializes in human resources, staff deficits among computing technology businesses in Mexico have reached a surprising 79%.

The Mexican Ministry of the Economy acknowledges that updating academic programs is a priority. They have invited industrial associations — from auto mechanics to mining, as well as aerospace and electronics — to their headquarters to gather suggestions and needs, which will be incorporated into the new curriculum.

“Four priorities have been identified with a focus on secondary and higher education: AI, electromobility, cybersecurity and semiconductors,” says Flores.

Need for invention (and patience)

In parallel, Claudia Sheinbaum’s government is promoting the Kutsari semiconductor research and design center—its name, of Purépecha origin, means “sand,” a reference to silicon, the abundant material that is essential both to the human body and to digital progress. Kutsari is focused on integrated circuit design, a complex process that typically takes about a decade of research and testing before it can enter production.

And precisely because this is an industry with long-term returns on investment, entrepreneurs say it is difficult to secure capital. Ernesto Conde, co-founder of Circufy, welcomes Mexico’s plans to grow its innovation ecosystem, though he stresses the need for tangible actions. He also calls on venture capital investors to take a closer look at the sector.

For instance, he points to initiatives like those in Malaysia, which in March announced a $250 million investment over 10 years to acquire intellectual property from British firm Arm Holdings, whose semiconductor designs power much of the world’s smartphones — part of a strategy to become a titan in a market that consulting firm McKinsey estimates could reach $1 trillion by 2030.

“In this industry, we need capital, but we also need patience and time for things to incubate,” says Conde. “Like I always say, we are in Jalisco, where to make tequila one must wait for at least five years for one’s plants to mature. There are successful examples in this industry. We just need that kind of mindset.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.