Artificial intelligence sparks ‘Game of Thrones’ in the chip industry

The unstoppable advance of AI is changing the rules, creating new winners and losers in the increasingly important semiconductor sector. Here is a review of the battles being waged in the supply chain and the main players fighting for dominance

For the chip industry, 2024 is the year of bouncing back. The sector is rallying amid the rise of cloud platforms and artificial intelligence. According to the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, global chip sales rose by 16.3% year-on-year last January, to $39.7 billion, and are forecast to end the year 13.1% up from the $526.8 billion recorded in 2023.

These figure show that something is brewing in the industry, which plays a key role in all sectors. Nvidia — which saw its profit rise by 769% in the last quarter of 2023 — has become a symbol of this rise. Nvidia’s market capitalization rose to almost $2.2 trillion and the firm is threatening to overtake Apple to become the second-most valuable technology company in the world. The Dutch company ASML and Taiwan’s TSMC are also seeing record highs in the stock market, with shares surging 48% and 57.6%, respectively, in 2023.

Indeed, a few days ago, the ratio between the semiconductor sector and the S&P 500 soared past the levels seen at the pinnacle of the dot-com bubble. The chip rally has been buoyed by forecasts from firms such as the Wells Fargo Investment Institute, which revealed that in 2025, Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Meta will spend nearly $200 billion a year on building new data centers to manage the rise of AI. Adding to the furor were reports from consulting companies such as Canalys and Gartner, which predicted that AI-enabled smartphones and PCs will account for 45% and 43% of total sales of cell phones by 2027. None of these advances can happen without AI chips that can handle the massive amounts of computing power required for learning and inference in new AI-enabled applications.

Behind the optimistic forecasts lies a power struggle between the companies that make up the supply chain of this powerful and cyclical industry, which now moves at the pace set by AI. And each link in the chain is experiencing its own Game of Thrones, with winners (those who have jumped on the AI bandwagon early) and losers, the laggards who are struggling to make inroads.

Foundries firm up positions

Foundries — companies that manufacture logic chips for third parties — are in battle, with TSMC, Samsung and Intel engaged in the fiercest competition. Currently, the reigning leader is TSMC, which in 2023 recorded total sales of $69.3 billion, compared to Intel’s $54.228 billion and Samsung’s $50.99 billion. Its share of the global foundry market reached 57.9% in the third quarter of last year, a far cry from Samsung’s 12.4%, according to the latest TrendForce data.

The Taiwanese manufacturer — the main supplier of Apple and Nvidia — produces more than 90% of 5-nanometer chips and analysts expect it to maintain its leading position with the upcoming 3-nanometer and 2-nanometer chips, not only because of its advanced technology but also because foundry customers rarely switch suppliers. Moreover, as CEO C.C. Wei recently noted, although TSMC’s competitors may catch up in terms of processes and technology, “our success lies in the pure wafer foundry model and our commitment not to compete with our customers.”

But the battle for AI chips — which require advanced assembly of cutting-edge logic and memory chips — could change the leaderboard. TSMC knows this and has allied with South Korea’s SK Hynix to take on Samsung, the only one of the big three that can act as a one-stop shop in the manufacture of AI chips. In this context, it is important to remember that a new battlefront is also opening up over high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips for AI tasks, where SK Hynix and Samsung, along with U.S.-based Micron, are competing for control of the market. Samsung has said it aims to be the world’s leading producer of memory chips and system semiconductors by 2030.

Trailing behind, Intel and Japan’s Rapidus are also trying to join the 2-nm chip battle. The U.S. company — which undertook an ambitious reorganization three years ago after suffering major commercial and technological setbacks — is building foundries in Arizona, Ohio, New Mexico and Oregon. It will also begin building plants in Germany and Japan. Intel wants to be the second-largest foundry by 2030 and believes the pull of AI will drive demand for its server processors. It unveiled its own next-generation chips in late December.

The foundries business is set to make good returns this year, following a challenging 2023 due to high inventory levels across the supply chain, a weak global economy and a slow recovery in the Chinese market. AI is expected to boost annual revenues in the market by 12% to $125.24 billion. In 2023, it fell by 13.6% to $111.54 billion. Emilio García, an industry analyst, says that “it is possible that revenues will be positively affected by the recent 7.3 intensity earthquake in Taiwan and the drought, which will slightly strain supply chains at a time of high demand and raising prices.”

For Samsung, Intel and Rapidus, the challenge is attracting customers to expand their market share, but it will not be easy as TSMC has a very close relationship with companies such as Nvidia, AMD and Apple. They will have to show they have a competitive edge when it comes to technology and costs, although Intel will also play the Made in America card, which may be starting to pay off. At an Intel event in February, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said that the company would be a customer of Intel’s future foundries in the U.S.

The battle for AI chips

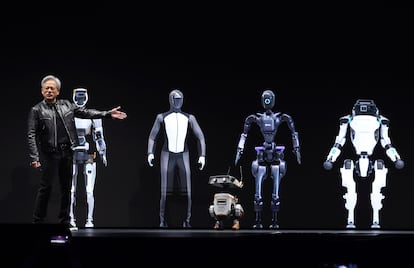

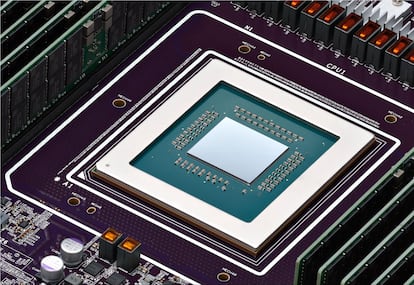

The rise of AI applications has created a strong demand for specific processing units (GPUs, CPUs with accelerators or hybrids). Nvidia, AMD and other companies such as Intel are vying to be the leading suppliers of these components, which are key to the operation of applications such as ChatGPT and Gemini. Tech companies are buying enormous volumes of AI chips: OpenAI acquired 30,000 for the launch of ChatGPT 4.0, Elon Musk bought 10,000 to develop Grok, Meta has reserved more than 350,000 for its AI service... And most of them have been bought from Nvidia, which has become the undisputed queen of the fabless AI chip suppliers.

Nvidia certainly had the upper hand. Its A100 and H100 products dominated the scene as early as 2022, so much so that U.S. trade restrictions on semiconductors were aimed at preventing China from accessing them. Copying or improving on Nvidia’s products and dethroning the company will be no easy task, as many of the AI algorithms rely on CUDA (its established software platform) and the design cost of its products is extremely high: its latest GPU, the GB200, cost $10 billion.

But could Nvidia’s reign come to an end? Its big rivals — AMD and Intel — are counting on a market hungry for competition, which will put a cap on the prices charged by Nvidia, which raised its gross profit margin from 57% to 73% in 2023. For the time being, AMD has launched two GPUs that have reportedly caught up with those of its competitor, and Intel announced on Wednesday Gaudi 3, an AI processor that they claim is more powerful than Nvidia’s H100.

Intel has also joined forces with Qualcomm, Google and other companies to form a coalition that seeks to curtail Nvidia’s dominance by going after its secret weapon: software that keeps developers tied to Nvidia chips. According to Reuters, the consortium, called UXL, plans to build a suite of software and tools to rival CUDA. The open source project relies on a piece of technology from Intel called OneAPI and aims to make computer code run on any machine, regardless of the chip and hardware that drives it.

Big Tech: the new rivals

Nvidia will not only have to face challenges from AMD or Intel. Some analysts like Emilio García are convinced that the biggest threat to its future will come from some of its main customers: Microsoft, Google and Amazon, the three largest cloud service providers. The volumes of components that will be needed in the coming years to drive AI “may make it profitable for them, despite the cost, to design the most suitable AI chips for their applications.”

Nvidia is aware of this, and in its latest product presentation, it unveiled a whole catalog of alliances with the three tech giants and an agreement with Meta to supply one of its latest products, the new B200. But this has not prevented the aforementioned big tech companies from testing chips from other manufacturers, such as Intel and AMD, and manufacturing processors designed by them.

In November, Microsoft unveiled its Maia processor, designed for customers of its AI platform Azure. On Tuesday in Las Vegas, Google — a pioneer in the field that launched its Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) in 2016 — revealed its TPU v5p accelerator chip and Google Axion, a new family of Arm-based processors, with which it intends to end its dependence on Intel and Nvidia. At the end of 2023, Amazon also presented its Trainium 2 chip for AI workloads, while Meta launched its first AI chip (MTIA) last spring. What’s more, OpenAI is looking for investors to launch its own AI chip supply chain.

“They have been developing these chips for years, but the emergence of generative AI has clearly accelerated their projects, because it is not advisable for them to be so dependent on Nvidia,” Emilie Jolivet, director of the semiconductor division of French consultancy Yole Développement, told the French financial newspaper Les Echos. In the same vein, Pat Moorhead, an analyst in the chip sector, told the Financial Times that the cloud giants “want supply options. They’re going to throw some business to AMD and some to Intel. They want a three-horse race.”

What impact these moves may have on Nvidia’s current position is pure speculation, but it appears that it will not take a heavy toll in the short term. The many years of work that have gone into creating tools and frameworks that make it easier to program Nvidia’s chips for specific tasks have led to an inertia that will be difficult to overcome.

And what about the machine manufacturers?

European giant ASML cannot rest easy either, as the battle between the manufacturers of the machines needed to produce the most advanced AI chips also promises to heat up. In this field, ASML has a virtual global monopoly in the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machine space. As a result of this dominance, the company increased its net profit to $7.8 billion in 2023, a rise of almost 40%. Order bookings rose to a record €9.19 billion ($9.98 billion) in the fourth quarter of 2023, up from €2.6 billion ($2.7 billion) in the third.

The company — which counts TSMC, Samsung and Intel among its main customers — is the most valuable tech firm in Europe, with a market capitalization of €302 billion ($321 billion). Nikon and Canon have struggled to make a dent on its wide lead. But Canon is hoping to close the gap with its Dutch rival with nanoimprint lithography (NIL), a new technology capable of producing 5-nm and 2-nm semiconductor chips.

But like the U.S., Japan and the Netherlands have imposed limits on the exports of advanced chip manufacturing equipment to prevent China from becoming a leading power in the chip industry. According to Emilio García, China is keen to develop its own chip-making machines to get around Western sanctions. “China is still far from finding a local replacement for EUV machines, but the fact is that it has already developed its own ecosystem to replace other types of machines required in manufacturing, such as those of Applied Materials,” he says.

Geopolitics also matters

Another important factor in this strategic industry is geopolitics. While the U.S., Europe and Japan inject millions of dollars to help national companies gain a foothold in the industry and attract production to their territories, China is also making big investments as it seeks to get around Washington’s increasingly strict export controls, which are designed to curb its progress in semiconductor technologies. With dozens of factories set to become operational in the next few years, China is gearing up to expand its chip manufacturing capacity, which is set to have a medium- to long-term impact on the global market.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.