Starlink satellites: Elon Musk’s other destabilizing power in Africa

SpaceX’s internet service offers faster connectivity and plays a positive role in developing underserved regions by providing coverage to rural areas that previously lacked access. However, it employs few locals and faces regulatory issues

The arrival of Starlink in Africa has shaken up the continent’s telecommunications market in less than two years. Developed by SpaceX, the company owned by South African tycoon Elon Musk, this satellite internet service not only offers significantly faster connection speeds than its competitors but also provides connectivity to rural areas far from terrestrial cable infrastructures or Wi-Fi repeater towers, thanks to its network of more than 6,000 satellites. Applications like telemedicine and digital education resources are some of its most valuable contributions in the 17 African countries where it is currently available.

However, Starlink’s business model — characterized by few African employees, limited investment in infrastructure, and aggressive practices like sudden price hikes —overshadows the positive impact of its expansion. The company also faces challenges in complying with national communications laws and resistance from state monopolies in some countries. A recent example is Namibia, which ordered Starlink to cease operations last week, accusing the company of operating illegally because it does not have a license in the country.

“Starlink has two major competitive advantages,” explains Nate Allen, a cybersecurity expert at the African Center for Strategic Studies. “The first is that it provides service via low Earth orbit satellites, which allow for internet speeds much faster than those offered by terrestrial providers.” The second, Allen argues, is its potential for rapid expansion. “What could really change the rules of the game is if Starlink is able to launch even more satellites in the coming years, because it could enter into direct competition with terrestrial providers based on costs, which could dramatically shake up the telecommunications market across the continent,” he says.

The upheaval Allen refers to is one of the major concerns surrounding Starlink. “If it becomes a monopoly, it will eventually control prices,” he warns. “In some niche markets, especially among those who need fast internet, Starlink is already bordering on monopoly status.”

The case of Okaka, a rural town in Nigeria’s Oyo State, exemplifies both the benefits and the risks associated with Starlink’s growth. For more than a year, Okaka’s students have had access to high-quality open-source educational materials through a scholarship program facilitated by the consultancy Space in Africa, which brought high-speed internet to the area via Starlink. “The goal was to provide these students and teachers with affordable access to high-quality online resources,” explains Temidayo Oniosun, director of Space in Africa and an expert in the continent’s satellite industry.

However, without Space in Africa’s support, Okaka’s educational community may struggle to afford the expected price increases for a service that has revolutionized the area’s educational landscape — one that, according to UNICEF, is crucial for ensuring equity in global education. On September 30, Starlink unexpectedly and unilaterally announced that it would double rates for Nigerian subscribers within a month. Following pressure from the Nigerian Communications Commission, the company “temporarily” reversed the decision. However, Starlink indicated in a statement that it would implement the price hike once it resolves these “regulatory challenges.”

This price increase is possible because of Starlink’s policy, which does not offer contracts. “Starlink does not require a contract. Service is billed on a month-to-month basis and you can cancel at any time if you decide the service is not a good fit for you,” the company states. This flexibility, however, also allows Starlink to alter its terms of service at will.

Local competition

“Their initial business model was to use global pricing in Africa, with products costing around $100 a month [95 euros], but then they understood that they had to adopt a different strategy and compete with the prices of local technology companies,” Oniosun explains via video conference. That is why, he continues, “in some countries it costs $20 a month and in others $30 compared to the $100 it costs in the United States.” The result, according to the Nigerian expert, is that “Starlink has disrupted the African market and caused many telecommunications companies to lose subscribers.”

There is great potential for Starlink to expand its business in Africa. “From a continental perspective, the average internet connectivity in Africa is 47%, which is lower than the world average, which is 66%,” explains Michael Markovitz, director of the Media Leadership Think Tank at the Gordon Institute of Business Science at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

However, despite the seemingly low prices, Markovitz questions how many people will actually be able to afford the service. “It will be difficult for most of those who cannot afford to buy a cell phone, although it will be very competitive for people who can afford it in rural areas, such as farmers or companies in small towns, where the connectivity offered by mobile operators is expensive” and slow.

The key question when assessing Starlink’s impact, according to Markovitz, is: how many subscribers does the service really have? In Nigeria, where Starlink ranks as the third or fourth-largest internet provider, there are fewer than 30,000 users, compared to South Africa’s MTN, which has nearly 77 million users in the country, Markovitz explains.

While high-speed internet expansion could benefit the African economy, experts point out that Starlink’s business model “does not leave a significant footprint on the continent” because it requires little terrestrial infrastructure.

“The big concern for many countries is what Starlink could mean for the future of telecom companies, many of which are African-owned or state-owned and which employ many Africans who pay a lot of taxes in Africa,” Allen reflects.

For example, in Kenya, Safaricom “according to its own data, supports up to 1.2 million jobs and directly employs about 6,000 people, making it a business that generates substantial tax revenue for the government,” notes the analyst from the African Center for Strategic Studies. Oniosun shares this concern: “Starlink does not have a large number of employees in Africa, and the few it has are foreigners who come to the continent.”

Despite this, Allen believes that Starlink “will continue to expand, especially among sectors that need fast connectivity.” “It is quite difficult to beat Elon Musk’s company at the moment, although its future will also depend on cost and how it competes directly with other providers in the future,” he adds.

Another challenge, according to Markovitz, will be how Starlink adapts to the regulations of each country. Namibia recently forced the company to cease operations due to its lack of a license, a measure Cameroon took earlier this year, even ordering the seizure of Starlink equipment at its ports.

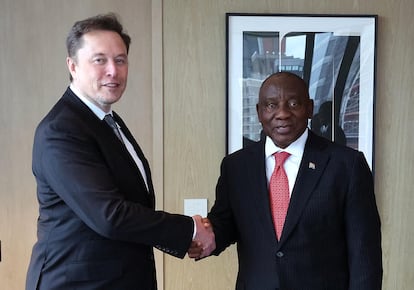

“In South Africa, Starlink still doesn’t have an operator’s license because it doesn’t comply with legislation,” which requires 30% Black ownership of a company, Markovitz explains. In South Africa, where 75% of the population has internet access, competition is much greater, he adds. “Musk has met with [South African President Cyril] Ramaphosa, and there are reports that the government will make an exception, but it’s very difficult for this to happen in a democracy because the law is very clear,” he concludes. However, he warns: “Elon Musk is in no hurry. He’s the richest man in the world. He has a strategy to continue launching satellites, and that is what he will continue to do.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.