The Chinese economy is losing steam: Why that should worry us

The Asian giant’s National Congress convenes in the midst of a slowdown caused by a deflated real estate sector and strict anti-Covid measures

It’s remarkable how real estate bubbles always seem to burst in the same places: big city suburbs, abandoned farmlands and empty lots where rows of empty concrete shells rise above roads closed to traffic and cheerful billboards touting middle-class dreams. “Central Mansion,” announces one such billboard in a residential development about 30 miles (50 kilometers) from downtown Beijing. Unfinished projects stretch in every direction, including a cluster of apartment buildings owned by Evergrande, a Chinese developer that has the distinction of being the most indebted real estate company in the world, and that has now become the poster child for China’s deflated real estate sector. At the entrance to Evergrande’s Royal Peak apartment complex is a gatehouse where visitors have to scan a QR code to confirm that they are Covid-free. The empty buildings and the ubiquitous Covid checks, a product of China’s ambitious zero-Covid strategy, have come to symbolize the challenges facing the world’s second-largest economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned in mid-October that the Asian giant’s economic slowdown is one of three major threats to the global economy; the other two are Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and persistent inflationary pressure. The international lending agency based in Washington, DC cut China’s projected real GDP growth forecasts to 3.2% in 2022 and 2.7% in 2023 (down from 8.1% in 2021), according to the World Economic Outlook report released on October 11. This is well below Beijing’s target of 5.5% GDP growth for 2022 – when China stumbles, the rest of the world takes notice.

The IMF is not alone in its gloomy forecasts for China. The World Bank is predicting that the country will fall from its 30-year reign as Asia’s top economic locomotive due to global uncertainty, shrinking domestic consumption and declining exports. It is forecasting meager 2.8% GDP growth in 2022, which means that China will grow less than all the other countries in the East Asia and Pacific region for the first time since 1990. The World Bank’s economic forecast blames the same factors for China’s slowdown: anti-Covid measures that disrupt supply chains, industrial and service production, and domestic sales and exports; and a real estate sector hobbled by pre-existing difficulties aggravated by unsustainable debt accumulation by developers. On a somewhat positive note, the World Bank reported that the country’s “systemically important banks have limited, direct exposure to real estate sector lending.”

Declining exports

Other warning signs have been cropping up as the year goes on. Exports of Chinese goods have been on a downward trend. According to data compiled by Caixin, a Beijing-based business and financial news outlet, export growth dropped from 23.9% year-over-year in the third quarter of 2021, to 12.3% in July and August of this year. After three straight months of growth, service sector activity contracted in September, reported Caixin, as did the manufacturing activity index, which has now fallen for two straight months.

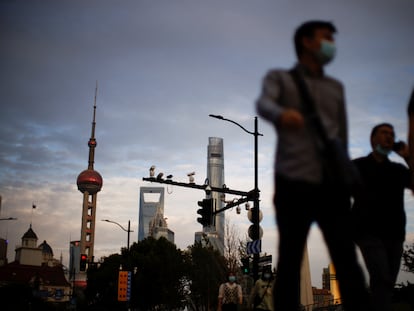

The world watched anxiously as the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party kicked off on October 16. Every five years, delegates representing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 96.7 million members convene to elect its leaders, and it’s widely believed that Xi Jinping will be reelected as the CCP general secretary for a third term, unprecedented since the days of Mao Zedong. In his opening speech, Xi defended China’s zero-Covid approach to the coronavirus pandemic and emphasized continuity rather than change. The anti-Covid strategy is a controversial topic for a pandemic-weary populace, and even sparked a rare political protest at Beijing’s Sitong Bridge on the eve of the National Congress.

China is one of the few countries that still maintains a strict zero-Covid strategy, which involves massive testing and total or partial lockdowns when cases are detected. In the spring, as most of the world removed their face masks and decided to coexist with the virus, Chinese authorities locked down Shanghai for more than two months. In September, more than 30 cities were under partial or total isolation affecting more than 65 million people. China has also strangled inbound foreign travel by requiring quarantines of up to 10 days to enter the country, restricting visas, pushing ticket prices into the stratosphere and causing frequent flight cancellations.

It does not appear that the Covid containment policy will change any time soon. The CCP-owned People’s Daily news outlet recently published an article defending the “dynamic zero-Covid” strategy, praising its results. Chinese leaders maintain that containing each outbreak before it spreads and overwhelms the country’s health system, is more profitable than trying to live with the virus, as the United States and European Union are doing.

A recent report from the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China states, “China’s isolation from the rest of the world resulting from its adherence to an inflexible Covid-19 policy, indicates that, for the time being, ideology trumps economics… While China once shaped globalization, the country is now seen as less predictable, reliable and efficient,” causing a “loss of business confidence” and opening the door for “other emerging markets” in the region.

Zhang Jun, director of the China Center for Economic Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, does not expect the announcement of any initiatives at the National Congress aimed at restoring the battered real estate sector. In a phone interview with EL PAÍS, Zhang said, “I think China’s leaders hope that the economy will find new sources of growth,” and will choose to promote high-tech and curtail traditional industries. “Having the real estate [sector] remerge as a primary economic engine is not consistent with the objectives of the [CCP’s] leadership.” But he is confident that Beijing won’t make any major economic moves until the new government takes over in March 2023.

Evergrande’s looming shadow

Beijing has been taking a few measures to prevent the complete collapse of the real estate market. Chinese property developer Evergrande is the most indebted real estate company in the world, and first defaulted on dollar-denominated debt obligations in December 2021. But these timid government measures have had little effect so far. New housing prices fell for the 12th consecutive month in August, residential sales plummeted 30% in the first eight months of 2002, and investment fell 7%, according to data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics compiled by Bloomberg.

With an eye on stalled development projects all over China, the CCP Politburo, the country’s top decision-making body, urged “stabilization of the property market” and said local governments would be responsible for ensuring the delivery of pre-paid housing currently under construction. The announcement was made after home buyers initiated a mortgage boycott to protest all the unfinished housing projects in the months leading up to the National Congress. In September, the People’s Bank of China announced that it would allow some local governments to relax mortgage loan requirements for first-time homebuyers in an effort to stimulate the housing market

Zhang Jun compares Xi’s decade in power to “the progressive era in the United States” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries when popular movements and associations were formed to tackle the problems of rapid industrialization and urbanization that followed the US Civil War. “Xi has tried to deal with these problems at the cost of a slowdown in growth,” said Zhang. In his view, China’s growth rate emerging from the pandemic will be in the neighborhood of 5%, a far cry from the heyday of the early 21st century.

A Sputnik moment

Regarding Chinese innovation, multinational financial giant Citigroup believes that we could be facing another “Sputnik moment,” a reference to the late 1950s when the Soviet Union shocked the world by launching the first satellite into orbit. Citigroup experts stated, “Heavy public spending on research and development, a large domestic market and highly skilled talent pool put China in an increasingly competitive position with industrialized economies.” They also believe the China’s cheap manufacturing model will shift to other countries.

Scott Kennedy, an expert on Chinese economics and business with the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, recently went into quarantine to enter China for his first in-country field work since the pandemic started. After flight cancellations and other misadventures, Kennedy finally arrived in Beijing to find a country where “control has been ratcheted up” in several areas. “If you look at the level of intervention in the economy, I think it has increased,” he told foreign correspondents.

Kennedy says that during his first few years in power, President Xi was waiting to see if market mechanisms would solve some challenges, such as housing. But after the turbulence of 2015 and 2016, the devaluation of the yuan, and China’s stock market turmoil, he says the government “got nervous. Since then, we’ve seen more and more intervention in the economy.”

Over the past decade, the Asian giant has taken a few steps forward and a few steps backward, says Kennedy, calling it “a mixed record.” He cites the country’s progress in electric vehicle manufacturing, which is heavily subsidized by the government. China is also making progress toward the government’s goal of “moving up value-added chains, and strengthening basic science research and [its] applications.” But in today’s interconnected world, no country can successfully innovate on its own, he says. “It doesn’t matter if you’re at the front, in the middle, or at the back of the pack – you always have to depend on everyone else.” China and the United States would face “monumental problems in their ability to innovate and increase productivity” if the world becomes more isolationist.

The China-US relationship is at its lowest ebb in decades, and suffered yet another setback when the US struck a new blow against China’s technology sector. The new semiconductor chip export restrictions are aimed at curbing Beijing’s access to cutting-edge technology that it can use for technological or military development.

Scott Kennedy calls China a “fat technology dragon that is capable of innovation, but wastes an incredible number of resources in the process.” He doesn’t believe they will ever achieve absolute self-sufficiency – that’s “like waiting for Godot.” In that story, Godot never arrives.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Sinaloa Cartel war is taking its toll on Los Chapitos

- Oona Chaplin: ‘I told James Cameron that I was living in a treehouse and starting a permaculture project with a friend’

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Why the price of coffee has skyrocketed: from Brazilian plantations to specialty coffee houses

- Silver prices are going crazy: This is what’s fueling the rally