‘Sextette’: The story of Mae West’s final madcap movie

The 1978 production remains one of the worst films in cinematic history. But 45 years after the star’s death, it is also seen as her final, daring attempt to assert herself

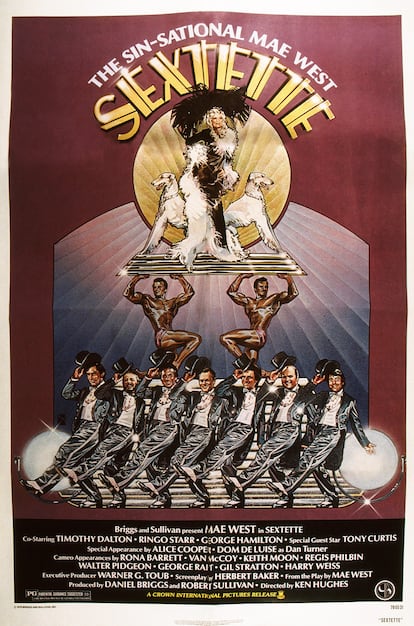

Mae West made her exit in grand style, starring at age 85 in a major Hollywood production, flanked by an intergenerational quartet of leading men — Tony Curtis, Timothy Dalton, George Hamilton, and Dom DeLuise— and surrounded by rock stars like Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, and Alice Cooper, all under the direction of a prestigious filmmaker. At this point, it matters little that Sextette, the 1978 film that became the swan song of a legendary actress, was a cinematic abomination and a financial disaster —a movie that cost between $5 and $8 million and grossed less than $50,000. As EL PAÍS put it at the time: “A laughable comedy, an absurd relic perpetrated with the collaboration of top pop figures. More to cry over than to laugh at.”

What is Sextette about? In short, it’s about how the actress and sex symbol Marlo Thomas get married for the sixth time, and just as she arrives at the hotel where she plans to spend her wedding night, an international summit of politicians is underway to decide the fate of the world. Seeing Mae West at 85 dressed as a bride, lounging on a bed, or receiving constant flattery and propositions from much younger men might be funny or bizarre, depending on who’s watching and with what attitude. Given the film’s failure, audiences didn’t exactly view it kindly.

What matters is that West — who had returned to film after nearly 30 years of absence to take a supporting role in the likewise reviled Myra Breckinridge (1970) — chose, near the end of her life, to grant herself one last indulgence. She left for a few days the 300-square-meter penthouse in The Ravenswood residential complex, where she had lived since the late 1930s, and moved with her entourage, by then much diminished, onto a film set to make a movie.

For Ken Hughes, the man tasked with directing her in this final venture, the experience was traumatic. Twenty years later, he still hadn’t recovered from it. In a genuinely funny but somewhat plaintive article published in the Los Angeles Times, the British director defended his track record (“I directed Cromwell, Casino Royale, and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang”) and lamented that his good name would forever be tied to a calamity like Sextette.

His argument before the court of good taste was that he did what he could, but the project was impossible from the start, burdened with constraints so severe that not even Steven Spielberg could have salvaged it with any degree of competence or decorum. It was supposed to be a musical comedy starring an actress who could barely sing anymore, let alone dance or move around the stage with any ease. Almost everyone involved was there out of friendship, loyalty, or unconditional devotion to Mae West — starting with the two producers, a pair of die-hard fans barely in their twenties. The project began with a script written by West herself in 1959, and it had aged quite poorly, but the screenwriter, Herbert Baker, adapted it with excessive caution and reverence, unwilling to take liberties that might offend its author.

In short, when Hughes joined the project he found an entire dysfunctional constellation of planets orbiting a faded star, all determined to make “a Mae West movie” long after West had stopped being West. But the worst part, he argues, was dealing with Mae West herself — her frailty, her rigidity, and her complete detachment from reality.

Necessary accomplices

Their first meeting was, despite everything, promising. The producers flew to London to recruit Hughes and set him up in a luxury hotel just a stone’s throw from West’s Los Angeles home. They had already reached an agreement with him, but made it clear that the actress had the final say on whether he would direct Sextette. As soon as they were introduced, West took Hughes by the arm and led him off to lunch at her favorite restaurant. They spent a couple of “delightful” hours talking about everything under the sun, without the slightest mention of the film, and when they returned to the producers’ office, Mae said they would work with Hughes: “The guy is gentleman.”

The filmmaker began to grow uneasy as soon as rehearsals started. West made it clear that everyone else would be rehearsing — not her. She boasted that she had “never” done so and didn’t need to in the slightest, though she was willing to be present so the team would have the opportunity to meet her.

Once shooting began, a progressively more anxious Hughes realized that West — despite her apparent lucidity and overall excellent health, which allowed her to get around without a cane or wheelchair — struggled to recognize people she had just been introduced to and would not be able to learn her lines. Anything longer than four words was an insurmountable barrier for her. She even had trouble delivering, for the first time on film, the most iconic line she had written for the stage years earlier and repeated countless times: “Is that a gun in your pocket, or are you just happy to see me?”

The problem became evident in the first scene Mae shared with one of the supporting actors, an exchange of four very short lines. The actress needed 74 takes — a world record, in Hughes’s opinion — for a scene performed by a couple of professionals, not children or pets. West would walk right when she was supposed to go left, trip over a rug or her co-star’s foot, miss her cue, or was silent when it was her turn to speak. She, however, was delighted: “We made a lot of progress today, didn’t we, Mr. Hughes? How many scenes have we done already? If you want another take, I’m ready.”

From that point on, the director chose to lock himself in the studio’s ultramodern sound booth and give continuous instructions from there to Mae West, who listened — more or less — through a microphone hidden in her wig. But that wasn’t all. Mae, backed by her entourage, refused to grasp that the character of an irresistible seductress (Marlo Manners, one of those larger-than-life women) capable of bringing any man to his knees and even resolving an international crisis by investing just a fraction of her immense erotic capital, required a certain dose of irony when being played by an 85-year-old woman.

Hughes tried to explain this to her, but she chose to ignore his direction. Although Hughes tried to keep the dailies (unedited footage) from her, she managed to have her assistants show them to her, and she did not like what she saw. In particular, she couldn’t understand why the close-ups made her look like “an old woman”: “I guess you’re not using the right filters,” she protested.

She also insisted, quite forcefully, that cutaway shots be used of the male actors (especially Timothy Dalton, for whom she had a particular fondness) laughing uproariously every time his character made a witty remark. Hughes told her that this was typical of a stale, outdated comedy — nothing like the kind of films being made in the late 1970s —but West was inflexible: “The movie is supposed to be funny, isn’t it? If we want the audience to laugh, we should start by laughing ourselves.”

What’s more, the actress suffered frequent lapses during which she wandered off into the most unexpected corners of the studio. The whole crew would start searching for her and eventually find her sitting in front of the coffee machine or peering into the broom closet with a vacant expression. The shoot was so chaotic that Hughes, by his own account, eventually gave up any pretense of imposing order. He couldn’t wait to pack his things and return to London. So he let West do as she pleased and allowed her and her entourage to stew contentedly in their own juices.

A pity? It depends on how you look at it. West was able to give herself one last film. She barely understood what was happening, but according to most accounts, she had a wonderful time. She bid farewell to Hughes with a gracious remark: “Thank you so much for understanding me so well.”

Rise to fame

According to Barcelona-based psychologist Xavier Guix, the secret to happiness lies in not having great expectations. Cultivating friendships, taking care of your health, and resigning yourself to a certain mediocrity that suits your preferences and inclinations is enough to be at least moderately happy. Mary Jean West, better known as Mae West, tried for years to follow Guix’s formula for life. Raised in Brooklyn, the daughter of a lingerie model recently arrived from Germany and a terrible Irish boxer who ended up working as a private detective, West seemed genetically predisposed to settle for very little. But she had drive, talent, and charisma, and life ultimately pushed her toward ambition and excellence.

At 14, she was already dressing as a man, singing and dancing, and was the most precocious of New York’s vaudeville stars. At 18, she debuted on Broadway, and The New York Times hailed her as the new queen of the grotesque and subtly obscene. At 30, she began writing, directing, and producing her own shows and achieved unexpected success with Sex, the most libertine and provocative of her plays. A Manhattan court convicted her of obscenity and gave her the choice between a $100 fine and 10 days in jail at Welfare Island. True to her instincts, she chose prison, convinced it would be the best marketing campaign for her play. The 10 days behind bars were eventually reduced to eight for good behavior. She spent them signing autographs for the other inmates, giving interviews, and having dinner with the warden and his wife.

At 35, she defied censorship again with Diamond Lil, another cleverly risqué piece in her signature style, which she toured along the East Coast of the United States and was performed 323 times. And finally, at 39, in 1932, after resisting Hollywood’s siren call for five years, she made her film debut, thus beginning a late and atypical movie career that may not have made her entirely happy — but did make her one of the most famous women on the planet.

Final years

West recounts in her memoirs that she traveled to California in economy class with a return ticket in her pocket. Someone at Paramount insisted on recruiting the star of Diamond Lil, so the studio, then struggling financially, offered her a six-month contract with a monthly salary of $5,000; not a fortune, but enough to buy herself “a modest pearl necklace and an ermine fur coat.”

She was set to play a supporting role in a social melodrama starring George Raft, another smart kid raised in New York’s rough neighborhoods. Once she arrived, she discovered that her character was bland and utterly lackluster, and the director, Archie Mayo, had no interest in her. “The problem,” she told the producers, “is that you wanted to bring in a blonde with big boobs from New York, but I’m much more than that. I’m an excellent actress, a grand lady of the theater, so if you don’t want me to go home right now, give me at least a couple of good lines to work with.” They suggested she write them herself, and that’s exactly what she did.

The film, Night After Night (1932), was a success thanks largely to West, who injected a caustic dose of erotic comedy into what was meant to be a story of hardship and moral corruption. Mae stayed in Hollywood, recruited a very young Cary Grant for her next project — a loose adaptation of Diamond Lil — and continued steadily raising her ambitions.

By 1935, she had already become the highest-paid professional in the United States after the press magnate William Randolph Hearst. But the Hays Code — Hollywood’s exhaustive corporate self-censorship manual that went into effect in 1934 — ended up sabotaging her dazzling career. Suddenly, the actress who had been Marilyn before Marilyn, the muse of obsessive erotomaniacs like Salvador Dalí, the only American capable of competing in erotic capital with Marlene Dietrich, and the author of such memorable lines as “I only like two kinds of men, domestic and imported” or “Good sex is like good bridge. If you don’t have a good partner, you’d better have a good hand,” became, in the eyes of the moralizing press, an attack on good morals and “box office poison.”

West grew tired of playing cat and mouse with the censors. In 1943, after barely a decade of countercultural successes, she ended her film career. She devoted herself to her usual pursuits: living life, cultivating her public image, and doing some theater. She even turned down starring roles in Sunset Boulevard and an opportunity to work in Italy with one of her most illustrious admirers, Federico Fellini.

She didn’t need cinema, no matter how much cinema seemed to need her. And she never would have returned to it if not for a capricious whim in her old age that led her to make another couple of films —each worse than the last — in the final stretch of her life. No one went to see them, and perhaps not even she (it is said she fell asleep in her seat during the premiere of Sexette), but there they are, because a true legend of the silver screen chose to pour the last drops of her talent into them.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.