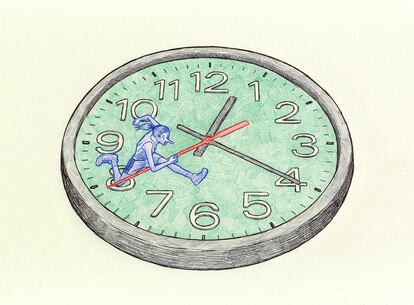

Why are we time poor?

Reflections on the addiction to productivity and tips to recover the best hours of our lives, as well as our peace of mind

As we get older, time management becomes a more pressing matter. Perhaps scarcity does create value, as they say in marketing. Why, then, are so many unhappy with how they use their days, hours and minutes? In the podcast How to Build a Happy Life, Arthur C. Brooks refers to our tendency to constantly increase the amount of work that we take into our free time; he argues that there is an alarming contrast between how we spend our time and what we really want to do with it.

An obsession with productivity drives many to cut back on their hours of rest—weekends included—for tasks that should be limited to working hours. This is particularly serious among entrepreneurs and freelancers, whose duties extend their tentacles to all corners of their calendar.

However, work is just one of the ways we have to keep ourselves permanently busy.

The most common answers to the question “What would you do if you had more time?” usually go along the lines of: “I would devote myself to what I’m passionate about,” “I would do more things with my family or my friends,” “I would talk more with my children.” However, these aspirations rarely become a reality because we never think we have the time. But that is an illusion.

Psychologist Xavier Guix says: “We are time.” Only the dead lack time. The question is how we use it. Ashley Whillans, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of the book Time Smart: How to Reclaim Your Time and Live a Happier Life, points out that 80% of professionals who participated in a survey defined themselves as “time poor.” However, just like making money without being able to spend it makes no sense, having success without time will not do much good. But how do we counter the not-enough-hours-in-the-day epidemic?

Professor Whillans talks about the “time traps” that make us devote most of it to being “productive.” One of them is prioritizing our career to the point of equating being always busy with being important. A gap in our schedule can make us feel lazy or like we are wasting time. In the U.S., according to Whillans, a female CEO at a party can boast of working 80 hours a week.

If productivity becomes a habit, spare time can only exist when we are bedridden due to a disease. Is that healthy? The key is deciding if we want more money or more time.

The problem is that we don’t know how to perceive spare time as the asset that it is; maybe money cannot buy it all, but you do require time for anything you want to do. Prioritizing this currency will fundamentally change your way of life. Let’s look at three practical measures.

Audit your calendar

We should take a look at what we do with our time outside of work. How much do we spend working after hours, in commitments that we are not interested in or in scheduled activities?

Look for truly “free” time

If we devote our time to too many activities and social commitments, then it is no longer free time. Whillans cites a study that showed that people who schedule too many things in their spare time end up seeing them as work and not enjoying them. We need to relax and improvise.

Learn to do nothing

Psychologist Martin Seligman states that Homo sapiens should actually be called Homo prospectus, because even when we believe we are doing nothing, we are planning the future: thinking about what comes next, what we have to do tomorrow, or in a more domestic setting, what we will cook for dinner. To enjoy true disconnection, avoid projecting and truly rest in the now. As Ovid said: “Take rest; a field that has rested gives a bountiful crop.”

The worst thing about stress

Being always busy is a recipe for stress: no matter how much we do, we will always feel like we have more boxes to tick, like we need more time. Andrés Martín Asuero, PhD in psychology and expert in mindfulness, explains that the worst thing about stress is not what happens from a biochemical point of view, when cortisol, among other hormones, is triggered; the worst thing is what we do about it. A stressful day is often dealt with by drinking alcohol, taking drugs or shopping compulsively, which adds an even bigger problem to our poor time management and stress.

Francesc Miralles is a writer and journalist who is an expert in psychology.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.