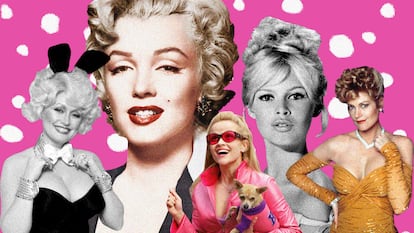

From Marilyn to Barbie: The rise and fall of Hollywood’s ‘dumb’ blonde

Andrew Dominik’s ‘Blonde’ is the definitive dismantling of the myth surrounding Monroe, who was pigeonholed – along with countless others – as an unintelligent, sexually available woman

For decades, the film industry has been perpetuating the misogynist cliché of the dumb blonde, a trope that emerged during conservative times. The post-#MeToo world seems uninclined to return to those days, except from a critical perspective that matches contemporary sensibilities. Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, which stars actress Ana de Armas, does just that. The film premieres on Netflix this week following its screening at the Venice Film Festival.

Blonde focuses on the complex relationship between the real person Norma Jeane Mortenson and the character she was required to play both on- and off-screen, the icon Marilyn Monroe. Ana de Armas received the best reviews of her career for her turn as Marylin Monroe in the film. Blonde is an adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’s novel of the same title, which fictionalized the talented, intelligent and sentimental woman behind the supposedly dumb blonde. The clash of her dual identities combined with other traumas, including an unhappy childhood and continuous episodes of abuse. But none of that was apparent to the outside world. Hollywood sought to project a perfect image of Marilyn Monroe, one that would satisfy the male gaze above all else. As essayist Laura Mulvey argued in her famous 1973 text Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, that was a basic requirement of the patriarchal order.

University of Oviedo researcher Socorro Suárez Lafuente, the author of the article “Marilyn Monroe: Masks and Looks,” agrees with Mulvey. “Hollywood exploited Norma Jeane’s desire to succeed, so she changed herself physically through operations and cosmetic changes to fit the time’s beauty standards. That ideal resulted from a patriarchal society; it served to make men feel strong and allowed them to exert their gaze on women.”

Monroe’s rise to stardom coincided with a period in which Hollywood – and the society it reflected – took a reactionary turn. That shift strongly impacted the female ideal. The era of strong and not particularly sexy women – actresses like Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Crawford – had ended. Even yesteryear’s blonde stars – the witty and bubbly Carole Lombard and the aggressively sexy Jean Harlow, for example – were out of fashion. The new blonde ideal had an hourglass figure and not much between her ears.

In Blonde, Norma Jeane says, “Marilyn Monroe doesn’t exist. Marilyn Monroe only exists on the screen.” Indeed, she was a fantasy come to life in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), director Howard Hawks’s memorable adaptation of Anita Loos’s book. Loos, a woman who stood out precisely because of her strength and independence, published the novel in 1925: in it, her protagonist, Lorelei Lee, was a frivolous and materialistic blonde girl, but she was by no means a fool. The character changed between the carefree and morally loose 1920s and the conservative 1950s.

The film version based its plot and humor on the interplay of contrasts. For instance, the disinterested and shrewd brunette (Jane Russell) contrasted with the materialistic and giddy blonde (Marilyn Monroe). But the most important contrast was the one between the blonde character’s apparent simplicity – she was unable to understand how to correctly use a tiara – and the wisdom about the human race behind some of her utterances. For example: “A rich man is like a pretty girl. You wouldn’t marry a girl just because she’s pretty, but doesn’t it help?” Or: “I can be smart when it’s important, but most men don’t like it.” The audience had to decide whether such lines were candid or cynical. That’s why Lorelei Lee fascinated viewers so much, her body aside.

Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955) dispensed with that ambiguity. In the film, Monroe played her role as the male protagonist’s forbidden object of desire. Gone were the days of Mae West and her active, overpowering sexuality: the 1950s blonde was expected to be the object of desire but never one who had her own desires. Reinforcing her archetypical nature, the film’s credits listed Monroe’s character as “The Girl.” The character did not exhibit the same sexual drive that she aroused with her mere presence. The screenwriters showed her habit of putting her underwear in the fridge to cool off. In the film’s most famous scene, she naïvely stood on a subway grate which blew her skirt up to reveal her legs. The heterosexual male viewer/consumer could derive comfort from her lack of guile. As Socorro Suárez points out: “The archetype was clearly fixed in the [popular] imaginary… It represented the predominance of the male gaze…and…made men believe that all girls could be for them.”

Marilyn’s childish voice in those films, which Ana de Armas’s portrayal of Monroe highlights, functioned similarly. The dumb blonde was understood to have the mind of a child and the voluptuous body of a young adult. That concept demanded a voice similar to a minor’s to make her seem both fragile and sexual at once. For that reason, Marilyn used her characteristic high-pitched, whispering diction, as if she articulated her words in sighs that left her breathless in the middle of a sentence. That’s the voice with which she is usually associated, but Monroe gradually shed it as she played more mature and complex roles, as in Bus Stop (1956) and The Misfits (1961).

Monroe was not an exception. In 1950, Judy Holliday won an Oscar for her role in George Cukor’s Born Yesterday. In that film, Holliday played a blonde woman who had a shrill voice and seemed unintelligent, though the character proved she was smarter than she seemed. In 1959, Monroe herself returned to the role of a crazy blonde in Some Like It Hot. In that movie, as Kathleen Rowe Karlyn points out in her book The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter, the role of the rebellious woman was supplanted by heterosexual men who cross-dressed for reasons of survival.

Meanwhile, American actresses Jayne Mansfield and Mamie van Doren and British actress Diana Dors were seen as sex symbols who could replace Marilyn Monroe. They were cut from the same cloth and could play similar roles, even if they had strong personalities in real life.

In France, Brigitte Bardot escaped the cliché of the dumb blonde to embody another kind of hypersexualized woman-child, while Mylène Demongeot of Good Morning, Sadness (1958) adhered somewhat closer to the original trope. Director Jacques Demy paid homage to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967), in which he cleverly reversed the roles: the blonde Catherine Deneuve played the spiritual character in search of romantic love, while the brunette Françoise Dorléac was more daring and found her better half in a mature and well-positioned man. But Demy’s partner, Agnès Varda, made the truly revolutionary gesture with her masterpiece Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), the story of a presumably dumb blonde who becomes aware of the emptiness of her existence when she is diagnosed with cancer and decides to take control of her life. In a key scene, the main character removes her wig and steps out of the narrow box in which society has confined her. In so doing, she stops being a doll handled by others and becomes a woman on her way to emancipation.

Federico Fellini, also in Europe, frequently resorted to a similar trope. Starting with Giulietta Massina in Nights of Cabiria (1957), he explored the theme of the good-hearted prostitute, which combined archetypes. He continued those efforts in La Dolce Vita (1960), 8 ½ (1963) and Giulietta dei Spiriti (1965).

However, in the second half of the 1960s, with the rise of countercultural movements, the dumb blonde ideal lost some of its relevance. Nevertheless, the decidedly un-countercultural Dolly Parton found success in 1967 with her hit song “Dumb Blonde,” which included the following lyrics: “Just ‘cause I’m blonde / don’t think I’m dumb / ‘cause this dumb blonde ain’t nobody’s dumb.” Parton would later quip, “I’m not offended by dumb blonde jokes because I know I’m not dumb. And I also know I’m not blonde.”

Around that time, Goldie Hawn’s irresistible talent and personality burst onto the scene. She began to demonstrate that being a hippie and a blonde ditz could coexist (There’s a Girl in My Soup, 1970). She continued that phenomenon through the 1980s, when she starred in Private Benjamin (1980) as a former hippie who enlisted in the army. Hawn’s dorky blonde character was an unintentional metaphor for the West’s political shift to the right. The new conservatism embraced sexist clichés and materialistic greed. Madonna’s 1985 hit “Material Girl” demonstrated that point: the music video for the song was based on the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Now, the blonde woman’s aspirations focused on the material, as evidenced by Daryl Hannah in Wall Street (1985) as well as Melanie Griffith in two of her best performances: an aggressive executive candidate in Working Girl (1988) and the unreliable southern belle in Bonfire of the Vanities (1990). In 1993, she also starred in a remake of Born Yesterday, the failure of which showed that some old notions no longer hold true.

In the 1990s, blondes shed their materialism, reprising the classic naivete and expressing vulnerability instead. Heather Graham’s roller-skating porn actress in Boogie Nights (1997) and Cameron Diaz’s role in My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997) are two such examples. Woody Allen’s filmography belongs to its own category. The humor of Mira Sorvino’s Oscar-winning character in Mighty Aphrodite (1995) stemmed from dialogues that portrayed her as uncouth and brainless. Characters played by Mia Farrow in Radio Days (1987), Jennifer Tilly (a brunette) in Bullets Over Broadway (1994), Evan Rachel Wood in Whatever Works (2009) and Lucy Punch in You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger 2010), among others, gave the impression that Allen took Monroe and Judy Holliday as points of reference, but stripped them of their complexity and retained only their most superficial aspects. For his part, Pedro Almodóvar has taken Anita Loos’s Lorelei Lee as a source of inspiration since his Patty Diphusa stories; the director allowed her hedonistic and multifaceted spirit to inhabit the characters of María Barranco in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), Verónica Forqué in What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984) and Kika (1993) and Miriam Díaz Aroca in High Heels ( 1991).

The turn of the century saw the release of Legally Blonde (2001). The movie’s main character, Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon), was a young Californian who overcame her image as a frivolous, emptyheaded woman to become a renowned lawyer. In the denouement, Elle delivered a speech extolling the virtues of believing in oneself and pursuing one’s dreams, thus serving as a vehicle for one of contemporary capitalism’s great mottos. In her own peculiar way, by the end of the movie Elle had become an empowered woman. She didn’t even need to change her hair color to do so, blazing a trail for blonde women to potentially be “re-signified” as feminist icons.

One might say that, because of her perseverance and determination the fictional blonde has tended to overcome the obstacles against her and achieve her goals. In the process, she defeated her enemies, who were almost always macho, self-serving men, and it became clear that what we had initially taken for stupidity was just an unconventional type of intelligence. But Suárez Lafuente is skeptical about that idea: “The archetype has changed little by little; it waxes and wanes depending on the era. But [it] persists because the patriarchy that created it remains.”

In recent years, the myth of the dumb blonde has lost momentum, which is a function of the political climate. One wonders how relevant the stereotype is now that feminism has become a widely accepted paradigm (or at least seems to be heading in that direction), and certain forms of degrading humor are no longer acceptable. But nothing can be taken for granted. A TikTok video showed Giorgia Meloni – the far-right Italian politician and the recent victor in Italy’s elections – asking for votes while holding a pair of melons, a joke of questionable taste that played on her last name, the fruit and her breasts.

Perhaps as an antidote to that, we can look to Barbie, the Greta Gerwig-directed film, which she co-wrote with Noah Baumbach. The movie focuses on the doll that was created in 1959 and represents the dumb blonde par excellence. But the title character, played by actress Margot Robbie, is not as striking as Ryan Gosling’s bleached blonde Ken. We already knew that a dumb blonde is often not blonde and almost never dumb, but thanks to Gosling, the archetype has taken a quantum leap: in the 21st century, the new dumb blonde might well be a cisgender man.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.