Stillz: ‘I’ve sacrificed my life for my work and I want to be valued’

The most sought-after music video director of the moment, the mind behind Bad Bunny and Rosalía clips, presents his first film ‘Barrio Triste’ at the New York Film Festival

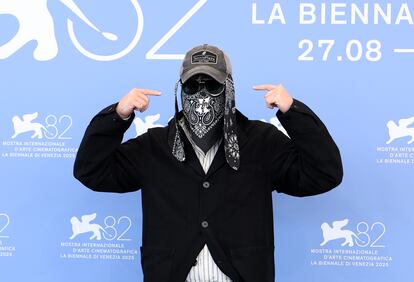

Excitement is building around Stillz (Miami, 26), one of the highest-regarded talents of his generation, not to mention among the most sought-after music video directors of the moment. He has brought to life more than 13 visuals for Bad Bunny, as well as the Puerto Rican mega-star’s photo book, which was sold exclusively at his residency in his homeland. Stillz has also directed Rosalía and J Balvin, and his acclaimed Polaroids serve as the best documentation of the contemporary music scene out there. Such a celestial profile is only augmented by the fact that he doesn’t show his face, nor share his real name, which might lead one to believe that he’s extravagant, unapproachable. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, what most stands out about this Colombian American is his humility and warm, friendly voice, which offers unhurried, smiling responses that indicate feet firmly planted on the ground. “I’ve been working in photography and video since I was 15 years old. I’ve been there at the start of a lot of peoples’ careers and have seen how their egos change when they get famous, that really scares me. At one point, I felt like I was headed that way, and I decided to hide myself,” he admits on a phone interview, his first with EL PAÍS. “With the arrival of fame, you also start to battle with yourself. I asked what is more important in my career, how I look or what I am creating? For me, what I’m creating is always more important. I have sacrificed my youth and my life for my work and I want to be valued for what I do,” he says.

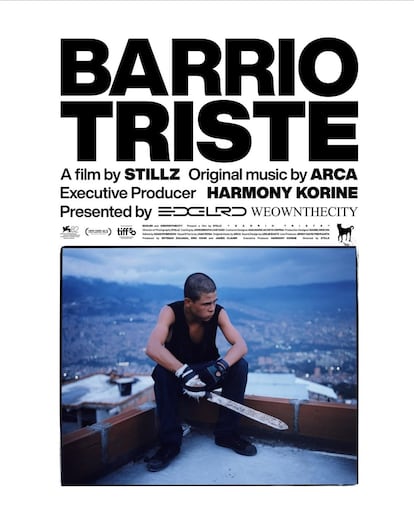

And now, part of that work is in the world of film. His first movie, Barrio Triste (2025) screened at the Venice Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival, and will show at the New York Film Festival on October 4, 5 and 12. It was produced by EDGLRD, the company founded by director and actor Harmony Korine, who invited Stillz to do a film with complete artistic freedom.

So was born the idea for Barrio Triste, its title the name of a real place in the area considered the Bronx of Medellín — a dangerous neighborhood featuring high levels of poverty and drug trafficking. Stillz ran across it while traveling with a food assistance organization, and while there, he realized how many of its residents came from elsewhere, from Venezuela and Los Angeles. “That was part of the inspiration to make the movie,” he says, adding that the film was shot in another area in order to show more of the mountains and villas so characteristic of Medellín, whose altitude allows for views of the entire city.

It was a risky shoot, but the crew hired a local person to track down places to film, and who also spoke with the individuals who oversaw the neighborhood, emphasizing that the production crew wanted the community to be part of the film. “We had a few scares, but there’s no problem when you work with respect and honesty,” explains Stillz, whose modus operandi leans towards cooperation and the organic rather than imposing upon communities.

The director says the film’s casting was the most interesting part of its process. They spent three or four months looking for young men in skateparks throughout all of Medellín, who they would interview in order to understand their energy and personality. Ultimately, they selected 10 of them and brought them together so they could get to know each other before the filming (a few originally hailed from the same group). Stillz says that he’s still in contact with them through Instagram and Facebook. “I grew up in the world of skateboarding in Miami and New York, skating in the streets, doing graffiti, robbing things from supermarkets,” he shares. “All those experiences form part of my youth and I’ve always felt very connected with that side of the world.”

“I think that skaters have something special; they’re people who don’t have a lot to do and every day, they invent something to do. They move around a lot, but I like to stay in touch,” Stillz says. He admits that he fell out of contact with some of the boys from Medellín when they lost their phone, but says that he’s trying to find them so that he can give them a new one. “They’re crazy about going to a theater to see the movie, but they don’t have passports. As soon as we get confirmed at a festival in Colombia, we’re bringing all of them.”

Music marks the tone and character of the film, via a soundtrack overseen by Arca, a Barcelona-based Venezuelan singer and producer. Stillz knew from the start that it had to be her. “I am training myself to hear music as I film and throughout the process of the movie, I got hooked on Arca’s first album. Later on, I couldn’t imagine the project without her.”

Stillz tells the story of contacting the artist, who initially said she was too busy. Even so, he went to Barcelona to meet her and work on one of her music videos. But it was difficult to find time to work on the soundtrack, and Arca had to leave for a show in Japan. So as not to let her get away, Stillz decide to accompany her, and they wound up doing another music video together. “Then a moment came and she told me that she was ready to see the movie. She started crying when she imagined the lyrics from her first album being laid over the images. The trip got extended, and we spent seven days in a hotel room putting together the soundtrack.”

In the film, there is a being that could be conceived of as an alien, zombie, or demon, but who, according to Stillz, is just a symbolic character. “It represents the monster, the nightmare of a child who listens to stories about kidnappings and deaths without understanding, without knowing what they mean,” he says. The creature isn’t represented using any special effects, but rather, played by a human being with a congenital anomaly who agreed to step into the role.

“I had heard people talk about him, I’d seen a childhood photo of him and his father, and I wanted to invite him to participate. It was difficult to get in touch, we didn’t know if he was still alive, but we found him,” says Stillz, who says that the 30-year-old actor was selling candy in the streets of the Colombian city. “I was happy. He was one of the most-sought after people on set. For me, he’s a superhero,” he says.

For Stillz, the best part is that the movie speaks for itself. He confesses that he doesn’t watch trailers, because he loves the feeling of being surprised, and that his only desire is to make people feel something, good or bad, when they watch his project. “Neutrality is the worst,” he says. He knows that his experimental film will be more difficult to understand, that it departs from traditional movies, but he wants to bet on the new. “I feel like I don’t have to follow everyone else’s lead.”

The director is a restless creator — in addition to photography and music video direction, he loves to paint. But right now, he’s feeling fulfilled by working on movies. “I don’t like repeating myself, so I don’t know what my next film will be like, but it will always have some Latino touch,” he says. That’s a key affirmation in the United States’ current, critical political moment, in which Latino stories are being rendered invisible.

Not even Stillz’s level of success can erase the identity crisis currently facing Latinos who were born or grew up in the country, nor familial trauma. “For me, it’s always been strange. I spent half of my life speaking in Spanish and then at 10 or 11, I began to speak more English because of school and then you become gringo and you don’t know who you are or where you’re from,” he says. “I’m not American, or Colombian, or anything. That’s why I’ve chosen to travel a lot to Colombia and other parts of the world to find myself, and I felt something very special in Medellín, because my family from there is full of stories. Sad stories, about kidnappings and deaths.”

Those are the tales he still has to tell, and the ones he mentions when asked if having achieved so much at such a young age, he still has dreams. “I also want to be an architect,” he adds. And he’ll probably do that, too.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.