‘It’s like they killed my little brother’: How children experienced and drew the assassination of John F. Kennedy

A new exhibit at the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, which is dedicated to the assassination, remembers the public’s reaction to the killing of the US president more than 60 years later

The window through which Lee Harvey Oswald shot President John F. Kennedy remains ajar on the sixth floor of an orange building in Dealey Plaza, Dallas. It’s a metaphor for how the memory of that assassination remains embedded, like a bullet, in the minds of those who were children at the time.

No child was prepared to experience the shock — televised on repeat and narrated by the broken voice of Walter Cronkite — of that three-act drama: Kennedy’s assassination before an applauding crowd, the assassin’s death at the hands of Jack Ruby in the basement of a police station two days later, and concluded by the president’s mournful burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

It all happened over the course of four violent days in the fall of 1963. In just 75 hours, America was plunged into disarray. And now, six decades later — when those children are in their seventies and Charlie Kirk’s assassination has rekindled passions with political bloodshed, cascading images, and a televised funeral — we can see the impact that Kennedy’s assassination had on the generation of baby boomers, who were born in the years after World War II.

For the first time we can see, in such graphic form, how some children, with chilling drawings and anguished voices, expressed the shock that the tragedy meant for them. And it’s all possible thanks to the reflexes and childlike sensitivity of an independent filmmaker named Richard Snodgrass. It was he who knocked on the doors of a school at the time and asked the students to draw and describe what they had felt.

That Friday in the fall, John was nine years old. He still remembers the silence that fell over everything around him. Ken was taking a 10-word spelling test when, suddenly, the classroom door opened: a teacher announced that the president had been shot. Everyone was taken down to the gym to watch television together.

Peter had never seen a teacher cry before. Kathi was ashamed of crying and buried her head under her desk… until she saw other classmates shedding tears as well. Harry was taken to church to pray with many other people. Gage spent hours crying at home with his mother and grandmother.

Ted was five years old and riding in his mother’s car when the radio broadcast the news. His mom said that something bad always happens to those who seek good. Victoria turned nine that very day and she — who didn’t know what “assassination” meant — was left without a birthday party. Every subsequent year of her childhood was marked by those three eternal letters: JFK.

Many children were scared. They were gripped by fear, by a strange sense of danger and by a profound sadness.

A few days after that shock, Richard Snodgrass became interested in how children reacted to the tragic events that were spewing from screens in every home across the country. Influenced by the cinema of the New Wave, he had already shot a film titled Legacy (1963), which captured the perspectives of children in Arizona on issues such as racism, divorce and nuclear apocalypse, just one year after the Cuban Missile Crisis. On December 9, the filmmaker began an experimental project at Sacred Heart School in Prescott, Arizona.

For a week, he locked himself in with 41 first-graders and talked with them about JFK’s assassination. They were aged five and six. He listened to each one, collecting their observations and feelings, both through art and the spoken word. The project produced some 400 drawings and three hours of audio interviews. The goal was to document how they were perceiving and processing that historic event.

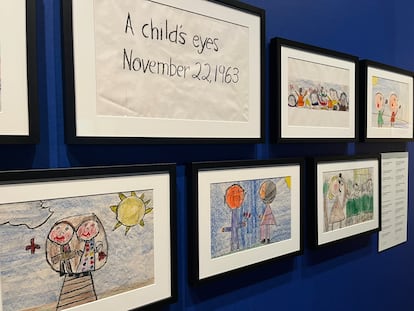

The children could only draw and describe from memory what they remembered seeing and hearing in the days before the killing. And now, for the first time in many decades, the drawings have come to light. They’re on display in the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, in Dallas. The museum, which examines the Kennedy assassination, is located in the same building from which Lee Harvey Oswald fired three shots at the presidential motorcade. He mortally wounded 46-year-old John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the second-youngest resident in White House history.

At times, the gallery of drawings borders on the gloomy: a rifle scope focuses on the open-top Lincoln Continental limousine in which the Kennedys were traveling, both surrounded by sinister black stripes. The president collapses in his wife’s arms after being shot. A family screams in fear upon receiving the news of the assassination. The coffin is draped in an American flag, while anonymous, mournful citizens pass through the Capitol. A police officer is about to fire his pistol outside the building. The first lady is praying at the hospital gates. The last rites are administered by a priest.

The short film that Snodgrass put together with all the material he collected has rarely been screened. But today, in the museum space, with old wooden desks for spectators, amid a 1960s setting, those children’s voices from Prescott’s Sacred Heart School resonate with the power of time capsules. The voices of those shocked children mingle with the drawings they made. They talk about how it was a very sunny day, with a little bird singing in the air and smiles on people’s faces. They talk about flags waving in the midday wind, touted by children perched on their parents’ shoulders (their schools had given them the day off to see the president). But suddenly, those voices, frozen in time, say that gunshots rang out. There was chaos. Sadness gripped the people.

The children emphasize that, above all else, there is sadness. One says: “I feel like my little brother was killed.” Another says: “It was like when my cat was run over, but she didn’t die. She’s all right now.”

The coffin holds a special preeminence in children’s memories. That mahogany coffin, weighing 400 pounds, dominated the cameras’ focus in the funeral procession to Arlington Cemetery. Kennedy’s youngest son, who turned three that same day, saluted the coffin. This became an iconic image of the turbulent 1960s.

The coffin also captured the memory of Deborah Sosin. Today, she’s a writer and editor. On that fateful day, November 22, 1963, she was nine years old. She remembers herself at the foot of her parents’ bed, glued to the 12-inch TV, which had a green plastic casing. Three years earlier, she had shaken hands with then-candidate Kennedy at a campaign rally. She remembers him as being handsome and tanned. But the memory that never fades is that of the coffin, draped with the American flag in an open carriage: the riderless horse, the rhythmic cadence of the snare drum. Nor can she forget the image of Oswald’s assassination in the basement of the Dallas police station. “I watched it a million times. His twisted face, the tall sheriff in the cowboy hat lunging after [Jack] Ruby, the confusion, the screaming. Suddenly, nothing made sense. Terrifying things were happening… we had to figure them out as best we could,” Sosin recalls.

It wasn’t just the children who suffered the consequences. Many people paid a high emotional toll from being exposed to a violent national tragedy that was repeated by the media, especially the three commercial broadcast television networks: CBS, ABC and NBC. A study of the adverse consequences of collective stress on pregnant women yielded startling findings after analyzing more than 30,000 cases. Women who were in their first trimester of pregnancy when Kennedy was assassinated had a 17% higher risk of premature birth when compared to those who had given birth before the crime. And, after comparing siblings born to the same mother, babies who were in the womb during the assassination were 22% more likely to be born prematurely than their siblings born beforehand.

Another study, authored by psychologist James Pennebaker, who analyzed the psychosocial stress generated by the killing, showed that, in the four years following, deaths from heart disease increased by 4% in Dallas, while murder and suicide rates also increased significantly in the city, which some began to call “City of Hate.”

There’s also research on the grief reactions to Kennedy’s death, expressed by kids who were admitted to the Children’s Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Michigan Medical Center. This study detected a wide range of emotions — anxiety, fear, sadness, confusion — that even extended to reenacting the event: one child used toy figures to recreate a funeral, while another organized a trial to convict the assassin.

That intense experience — concentrated between a Friday afternoon and a Monday afternoon — made it a traumatic and indelible event for many children. It’s a milestone in so-called “flashbulb memory,” those highly-detailed, autobiographical memories of circumstances in which a person learned of an event of great public impact (such as 9/11, or the Moon landing).

Stephen Fagin, curator of the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, has spent years collecting experiences that are linked to the Kennedy assassination. He has conducted more than 2,600 interviews for the center’s Oral History Collection. Most are with baby boomers, who experienced the trauma of November 22, 1963 when they were children. “Through these conversations,” he explains to EL PAÍS, “I’ve discovered that a common factor is the feeling of profound personal loss they experienced, regardless of their age, location, or political affiliation. For many, the loss was as profound as if a family member had died. Another common factor is the lack of professional help young people had, especially in schools. Without a real outlet for expression, most of the children kept their feelings bottled up.”

“That’s why, decades later,” he points out, “when they visit our museum as adults, some are confronted with repressed traumas that they were never able to resolve. Visiting the site of the shooting is, for many, a cathartic experience.”

Fagin says that the drawings in the exhibition, titled Colorful Memories, November 22 Through a Child’s Eyes, confirm that “no one is too young to be affected by violence, even from a distance. The trauma of that tragic weekend changed world history. But, on a deeply personal level, it also helped shape the mindsets of the young people who lived through it.”

After the farewells, the museum elevator opens. There are two more visitors. One is wearing a cowboy hat. The other, fair-skinned and in his twenties, is wearing a beige cap with the slogan: “I am Charlie.” In the plaza, a Black man, wearing an old Kansas City Chiefs jersey, is selling tourist newspapers about the Kennedy assassination.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.