Garth Ennis, co-creator of ‘The Boys’: ‘In most superhero comics, violence has no consequences’

The comic writer reflects on his book series, which was adapted into a hit show on Amazon Prime, watched by more than 55 million people

“What would happen if superheroes existed in the real world?” That was the question asked of Garth Ennis, 55, at the recent 30th edition of the Avilés International Comic Book Festival. His answer was simple: “A nightmare.”

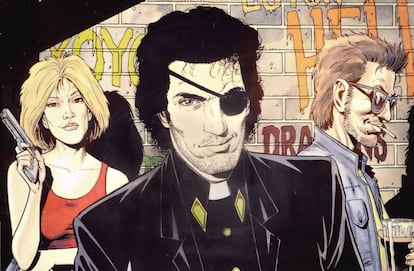

Ennis is one of the greatest comic book writers in the history of the medium. He created his own influential series that defined the 1990s and 2000s, such as Preacher, Hitman, and Crossed, and he has also written iconic runs on characters that marked an era, like John Constantine in Hellblazer or The Punisher, Marvel’s most violent superhero.

Like Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, and Warren Ellis, Ennis was one of the most illustrious writers to move from Britain to work in U.S. comics after making his name in a wildly popular weekly magazine of dark, fantastic stories: 2000 A.D., home to legendary characters like Judge Dredd. Ennis himself recalled in one of his talks in Avilés that, at the height of the publication, “250,000 copies were sold each week” — that is, a million a month.

But it was with the television adaptation of The Boys, his savage satire of the superhero genre for streaming giant Amazon Prime Video, that the popularity of his work reached an extraordinary peak. In its fourth season, The Boys drew 55 million viewers worldwide in just 39 days, according to figures released by Amazon Prime Video; the fifth and final season is expected in 2026. Why did Ennis, in a genre he isn’t particularly fond of, create his own major superhero saga — a comic spanning over 1,700 pages across 72 issues? The reason was to answer another question: what would happen if beings with near-divine powers walked among us?

“Watchmen [Alan Moore’s masterpiece, included by Time on its list of the best novels of the 20th century] already answered that question,” the Irish author tells EL PAÍS from a sidewalk café in Avilés. “And the answer was: things are not going to go well. Watchmen’s answer was: you terrify society with an external threat to force it to unite. Miracleman [also Alan Moore’s version], which I like even more than Watchmen, offered another possible answer: if you make everyone a superhero, no one can feel jealous of them, because they all have those powers."

"The Boys answers in a different way," he says. “My superheroes have the ego of a young pop star — but they also act as active members of society, perhaps saving the world or preventing disasters. That puts them somewhere between a pop star and a politician. Finally, they would be owned by major corporations — probably the most destructive force in human history. If superheroes could be real, Amazon and the others would have their own.”

Ennis takes the most terrifying implications of this hypothesis to its extreme in chapter 21 of The Boys, which he co-created with illustrator Darick Robertson. Inspired by the 9/11 attacks, the episode follows one of the planes hijacked by terrorists, which, in the world of The Boys, the superhero squad attempts to save. The carnage that unfolds — culminating in Homelander, The Boys’s version of Superman, abandoning the plane as it plummets onto a New York bridge — is unforgettable. The shocking and horrifying sequence stems from a rarely explored premise in the superhero genre: what if the person meant to be the savior is utterly useless and incompetent?

“They have no idea. They’re amateurs. They don’t have a plan. How does a plane work? Its aerodynamics? What happens if the tail falls off? [Homelander makes the insane decision to rip the tail off the plane, mid-flight, to try to save the day]. What happens, no matter how strong you are, if you don’t have any leverage? The thing is, these guys aren’t trained in combat. When the people on the plane rush at Homelander, the way he tries to get them off is like the squeals of a panicked child: ‘Get away from me, get away from me!’ But of course, with super strength, every time he pushes someone, he decapitates them. So it’s a massacre.”

One of the most distinctive traits of Ennis’s work is precisely that: raw, shocking, and visceral violence. His scripts insist that torn guts, broken bones protruding through shredded flesh, and copious blood be depicted in all their brutal detail. Unlike a movie or video game, the comic freezes a moment in time in each panel, which means that in works like his post-apocalyptic dystopia Crossed, scenes of extreme violence don’t just happen — they are fixed on the page, displayed in their full horrific glory. Unforgettable.

“Sometimes, I do it for satire. But in works like Crossed or The Boys, it’s for honesty," says Ennis. “I try to be as honest as possible about the effects of violence. I think it’s something that needs to be weighed very carefully. In most superhero comics, violence has no consequences. People kick each other, punch each other, explode each other… And nothing happens. Death doesn’t mean anything in those comics, because every time someone gets killed, you know they’re coming back."

“I prefer to show, sometimes, that the truth is that the consequences of those acts are terrible,” he continues. “That extremely horrendous things would happen. That’s why, generally, in my stories, when someone dies, they stay dead. And I think I’d like to encourage other writers to do this: to explore the consequences of violence.”

Ennis admits that his life is “sorted” thanks to the success of The Boys. But, unlike some of his contemporaries, his love for comics has made him resist Hollywood’s siren call: he does not want to see his vision “watered down.” Ennis is continuing the enormous, almost unmanageable task of researching war history and translating it into comics, and he is excited to write his first novel sooner rather than later.

Ennis, however, views the future with deep pessimism. He has even claimed that horror has become “obsolete” since someone like Donald Trump reached the White House. From Avilés, where he received a standing ovation, he warned: “I think idealism is dying. More and more, all over the world, I think all we are left with is pure survival.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.