Philip Kitcher, philosopher: ‘Life is a human project, not God’s’

The British thinker is an advocate of collective progress and laments our contemporary individualism. In an interview with EL PAÍS, he says that there is value in idealism, even when it is absurd

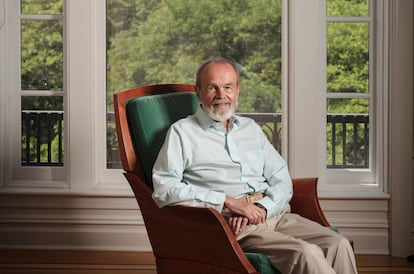

Philip Kitcher’s apartment overlooks Riverside Park in New York City. Through the large living room window, there isn’t only a flood of light, but also a wealth of greenery.

The 78-year-old British philosopher has lived in this noble building on the Upper West Side since he began working at Columbia University 25 years ago. For the past five years, Kitcher’s been the John Dewey Professor Emeritus of Philosophy. He says that he retired “to make room for others.” However, he assures EL PAÍS that he will continue researching and writing. This is good news, considering that his work is key to rethinking human nature and collective progress.

The London-born academic defines himself as “a horizontal thinker who connects the dots.” This ability to unite seemingly unrelated scientific and humanistic disciplines is one of the reasons he was awarded the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Humanities. It’s easy to detect his talent by reviewing the diverse themes that run through his 19 books: from mathematical knowledge to the ethics of the Human Genome Project, from the environmental crisis to education and moral development, passing through philosophical interpretations of Death in Venice (1912), or his analysis of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Unlike many intellectuals, Kitcher is a genuine humanist. He speaks little about himself and listens closely. He’s deeply concerned about the state of the planet and contemporary morality. It’s easy to feel comfortable in his presence; his serenity is infectious. His wallpapered apartment is lined with books, while photographs of his children and grandchildren fill the corners.

Question. Is it really possible to live a full, ethical and purposeful life in today’s world, which is so corrupted by war and injustice?

Answer. I think it’s more important than ever to try to be an ethical person. With the arrival of Trump, we’re living in a terrible time, but it all started long before that. We’re reaping the fruits of what happened economically 50 years ago, when we abandoned the idea of basic [public policies] that would be good for people. Instead, decisions began to prioritize efficiency and making as much money as possible over what was ethically correct.

I was fortunate to be born in a particular place and at a particular time. I benefited from social programs that opened doors and provided opportunities. But those doors are closed to those who come from families that aren’t wealthy. This troubles me terribly.

Q. You’re a clear advocate of secular humanism. How do you accept the meaninglessness of existence without anything to hold on to?

A. The essence of religion is to convince people that there is something greater than themselves and that they can contribute to the plan. But we can do exactly the same thing without needing a God: by doing our part to contribute to making life better. Life is a human project, not a project for God.

Q. That helps people live with purpose, but many people turn to religion out of fear of death, or in the hope that they’ll somehow be compensated for all that they have suffered.

A. I understand the fear of the pain that death can cause. Fortunately, palliative care is available. What I can’t imagine is clinging to the idea of an afterlife. It would be wonderful to live in a perpetual state of fulfillment, but I’m not interested in that. What I love about life are the relationships we create with other people, and I don’t think that can be transferred to another dimension. I’m not in favor of fostering false hopes. What we need to do is help people live the best lives possible, here and now, in this life.

Q. The new generations are taught that the important thing is to achieve power. Respect for culture and education has been lost. The world is no longer governed by moral principles, but by mere survival. Is there still hope for the children?

A. We’ve come to think of students as bits and pieces of machinery that can be fed into an industrial — or post-industrial — machine to generate productivity for a nation. [That’s why] we encourage all our students to go into certain subjects, because that’s the way that a country succeeds in the global marketplace. But if what we value in someone is their productive capacity, we have a very skewed idea of what a human being is. We forget that the essence of education is to teach people how to live, to create good citizens who live in communities, and learn how to distinguish what makes them unique.

Q. In one of your most recent books — The Main Enterprise of the World (2021) — you propose a profound reform of education based on philosophical thought.

A. I believe that each person should find what interests them and educate themselves in what matters to them. I also think of education as something that goes on throughout your life: I think people should have opportunities to go back to school and find out more about themselves and about what they can do.

We have to exert enormous resistance against our reality; there’s a huge misunderstanding about what education should be. Is it ultimately about what assets we possess? Surely what we want to do is produce happy and flourishing people who can work together cooperatively.

Q. Does the tendency toward individualism and competition affect other spheres, such as the environment?

A. Climate change is an ethical problem. In 1989, [British prime minister Margaret] Thatcher predicted that the only way to solve the crisis would be through a vast effort of international cooperation. The current political landscape discourages collaboration. At climate conferences, inadequate goals are set and the needs of the countries requesting aid aren’t met; nothing is achieved due to the politicians’ lack of ethical commitment. There are those — like Trump — who take advantage of this resistance.

The loss of ethics in politics isn’t only bad: it’s also catastrophically stupid. We’re facing global problems, but we’ve set up a socio-economic environment in which the cooperation that we require to solve these problems has become impossible to achieve. We are divided on how to approach the situation, and it is as if we are trying to analyze a war in the midst of a war.

Q. You decided to retire in 2020, but you’ve continued with your research. What are you working on now?

A. I’ve been asked to write a detailed commentary on Ulysses (1922). I used to teach a class on [James] Joyce at Columbia and I had a wonderful time. I also want to write about how imagination can help morality. I think of Dickens, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Cervantes’s Don Quixote! There’s value in idealism, even when it’s absurd. The Bible is considered a moral book and has ethically atrocious passages.

Q. Speaking of ethics, what do you think of the decision made by the university where you taught for so many years — Columbia — to bow down to government pressure, so as to retain its federal funding?

A. I would have loved for Columbia to have positioned itself like Harvard. But there’s a certain something about being the first victim of the firing line. It didn’t know how to do it. It was a terrible mistake.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.