Jessa Crispin: ‘Michael Douglas’s films perfectly represent the new masculinity’

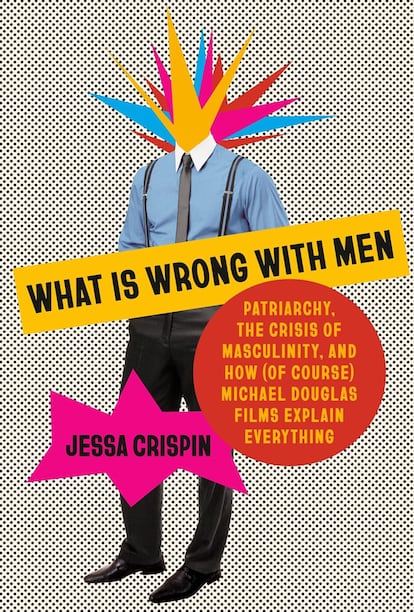

The American writer has published the book ‘What’s Wrong with Men?’ in which she asserts that the actor’s filmography explains the crisis of masculinity

Jessa Crispin (Lincoln Center, Kansas, 47) became known in Spain for her controversial feminist manifesto Por qué no soy feminista (Why I am not a feminist, Lince, 2017), based on the idea that the feminism of the time was useless. “I think the current feminism is even worse than when I wrote that book,” she says. Always willing to upset people or at least generate debate, she upset tarot haters — and there are quite a few — with The Creative Tarot: A Modern Guide to an Inspired Life (Alpha Decay, 2019), a book with which she sought to distance herself from “all that mystical, new age, crystal ball-and-cat stuff” to launch a blunt message: “You don’t have to believe in any God; it’s just a deck of cards.”

To talk about the crisis of masculinity, the author, far from pointing to Andrew Tate, focuses on Michael Douglas. Now, in What Is Wrong with Men: Patriarchy, the Crisis of Masculinity, and How (Of Course) Michael Douglas Films Explain Everything (Pantheon, 2025), she explains how the actor’s films from the 1980s and 1990s perfectly reflected the confusion and panic that men felt in the face of the social changes surrounding them.

Speaking about Wall Street, for example, she asserts that the film serves to explain how financial deregulation changed the way people build their careers, enrich themselves, and ultimately, even define themselves. Crispin posits that the corporate masculinity that destroys, not builds, and the figure of the breadwinner present in the feature film are part of contemporary masculinity. “He was a superstar and a symbol of the so-called ‘new masculinity.’” And yet, in most films, he’s clearly not having a good time. “He waves his arms, stares blankly, yells about how unfair everyone is to him,” she explains to EL PAÍS. “I decided to take seriously the idea that Michael Douglas represents a new masculinity and reflect on its meaning.”

When did you realize that Douglas’s roles might be somehow related?

During the pandemic, I started watching Michael Douglas films. I started with Basic Instinct, and meanwhile, social media was buzzing about MeToo, toxic masculinity, and cancel culture. Instead of being an escape route, Michael Douglas’s films started to help me think differently. What was on screen was clearly a clear example of toxic masculinity. However, there’s a context around this behavior that’s often omitted from social media conversations. So I started analyzing how the films influenced each other.

You assert that people tend to confuse patriarchy with men. What are the consequences, and how does it harm not just men, but everyone?

This is the danger zone of identity politics. At its best, it allows us to openly discuss how certain demographic groups are burdened by expectations, oppressions, and obstacles, and how they might need special consideration to integrate into our culture. At its worst, each individual represents their broader identity. Every white person becomes a representative of white supremacy and deserves to be held accountable for those larger sins, and so on.

If we approach politics only with a sense of entitlement and not obligation, nothing moves forward. You can’t build an agreement or a community if you just stand there yelling about what you’re owed for past mistakes. And that’s a real problem, especially on social media.

You say that men haven’t seen these changes as a sign of liberation, but rather as a loss of power. Should we help them?

We need to embrace the idea of solidarity: we’re here together, working for a common good, and I don’t need to agree with everything we believe or do as long as we treat each other with due respect.

The same structures that oppress men also oppress women. The financialization of every aspect of human life, the disappearance of the common good, the open-air exploitation of every inch of the earth for profit — this is screwing us all over. We have common goals, so it makes sense for us to work together to solve the problems.

Scott Galloway says that “the most dangerous person in the world is a broke and alone young male.” What do you think about that? Because it seems like helping men is fundamental, almost a matter of survival.

I’m not really keen on Galloway’s rhetoric about masculinity. I know he has very strong opinions, but I’m not sure I agree with many of his conclusions. I don’t think the most dangerous person in the world is a broke, lonely man. That’s the kind of incel hysteria we had a few years ago. I think the most dangerous person in the world is a drug-addicted billionaire with no sense of responsibility: Elon Musk.

Why is it so difficult to talk about masculinity?

Because femininity has been conceptualized, theorized, written about, and debated for over a century. Masculinity, not so much. At least not rigorously. If something hasn’t been satisfactorily defined, it’s difficult to fully understand.

What are the consequences of masculinity being more individualistic than ever?

If everyone only cares about themselves, pursues individual goals, and sees those around them as competitors rather than collaborators, look what happens. This is present in every aspect of today’s life. It’s the hustle culture, the political polarization, the social media frenzy... It’s Andrew Tate. How do you build a coalition when everyone approaches everyone else with suspicion and a domineering attitude?

What does feminism have to do with Michael Douglas?

Feminism has everything to do with Michael Douglas. In the three films I highlighted in the section on Michael Douglas and women, the reason he feels so bewildered and confused is because women have radically changed their expectations about their careers, their lives, their money, their power, and their very identity. If you’re going to be in a relationship with someone, what happens to them changes you, forces you to adapt. But Michael Douglas (the character) doesn’t believe he has to adapt; rather, the world should adapt to him.

On the Alec Baldwin podcast, Michael Douglas mentioned that he’s always been amazed at how many men approach him on the street and tell him that Gordon Gekko inspired them to go into finance. How is it possible that so many men find a villain inspiring?

Well, look at him. He’s got a great car, cool suits, prostitutes on call, a huge house with expensive artwork on the walls… He’s winning. In this new financialized world, morals and ethics are for the naive. Whoever dies with the most toys wins. Gordon Gekko has the most toys, and people saw him as someone to emulate. And not just men.

I think this was part of the problem with a lot of movies that tried to portray antiheroes as someone to be understood but despised. Look at all of Scorsese’s films. Those guys are cool, even when they’re stomping on someone’s face. ‘How could they not be cool, they’re on TV!’ There’s something inherently glamorous about filming someone, regardless of whether you’re doing it to show what an idiot or moron they are. People quoted serial killer Hannibal Lecter for years, and they still do. ‘Oh, look at him, he’s great, he’s on TV.’

How does Fatal Attraction capture the disorder of masculinized women?

I think it’s important to say that, in the nightmare vision of men, Alex represents the unhinged, masculinized woman. There was a lot of concern in the 1980s, when the film was released, about how professional women would end up crazy and alone, ruined by their empty wombs. It’s nonsense. The professional woman Alex represents (even with a man’s name) has an empty apartment, no hope of marriage or family, and is driven mad by her need for Michael Douglas’s love.

Why is the problem with white men a problem of national identity?

I don’t know if this is just a white male problem, but the appeal of populism and authoritarianism intensifies in times of economic hardship and social turmoil. When you feel your social standing or material resources are threatened, it’s easy to fall into paranoia, something populist leaders and movements exploit: “Germany for Germans only” or “America first.”

Why do you think the construction of the midlife crisis in men marks the moment when the male imagination became separated from reality, and how did it help them save their dignity from the truth?

This male midlife crisis fantasy rose to prominence in the 1980s. The man who leaves his wife for a much younger secretary and a sports car was something that was plastered all over the media. Michael Douglas plays a couple of versions, perhaps most obviously in Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, where he can’t even take his son to school because he only has a motorcycle. But if you look at the statistics, what was happening in the 1980s, a time of rising divorce rates, was that women were leaving their marriages, not men. Men were rejected and kicked out of their homes, and it was wives who were throwing their husbands’ belongings out the window. It’s the idea of “you can’t fire me, I’m quitting.” To protect yourself from intolerable information (your wife has rejected you), you construct a fantasy in which you are still in control. This fantasy was reinforced by countless movies, TV shows, men’s magazines, and so on. All to protect men from the intolerable information that they were disappointing their wives and considered unnecessary in the domestic sphere.

In fact, last year you asked why women can’t just admit they’re going through a midlife crisis. Why do you think that is?

I think because women bought into the midlife crisis fantasy, they can’t admit that they, too, might act selfishly. Let’s be clear: the midlife crisis is real! Gail Sheehy first documented it as a phenomenon among women who, once their children are less dependent on them or once their lives stabilize after the chaos of youth, begin to wonder if anything more might be possible. I think men experience midlife crises too: “Is this it? Is this forever? Is anything more possible? How have I compromised instead of going after what I really want?” But the fantasy is the idea that men experienced this as an empowering moment, leaving behind stagnant marriages and an unsatisfactory car. That’s the narrative a person builds about themselves to avoid realizing that, in reality, they’re just being irritating, selfish, and erratic. I think with writings like Miranda July’s All Fours and Lyz Lenz’s This American Ex-Wife, women began to construct their own midlife crisis fantasy. “I’m becoming sexually fulfilled! I’m on a spiritual journey! I’m exploring my true self!” That may be true, but it sounds like you’re just cheating on your husband and being a jerk.

As women have expanded their reach, how have men tried to protect their masculinity?

There’s a real paranoia about male behavior among a certain segment of men. They can’t wear pink because that’s gay, and holding hands with a woman is also gay. This kind of discourse is very common in Andrew Tate’s world, where everything you do, say, or experience could express a shameful, hidden femininity. So you have to be constantly on guard to make sure everyone knows you’re a real man.

It’s funny, I wrote an essay about this about 10 years ago. I noticed that all the socialist men who claimed to be left-wing, progressive, and woman-loving dressed scruffily, and in a very intentional way. They sported baggy T-shirts, hideous shorts, and scruffy beards. And to me, that signaled hostility or fear of femininity; they had to prove that, while they weren’t “toxic” men, they weren’t feminized either. Anyway, I wrote an essay about this and received so many hateful emails from men who claimed to be socialists that I thought it was funny.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.