Mario Vargas Llosa’s great loves: His aunt Julia, his cousin Patricia, and socialite Isabel Preysler

The Nobel Prize winner had a romantic life worthy of a novel. He married a relative 12 years his senior, then left her for another one. In 2015, he began a high-profile relationship with a star of gossip magazines

The brief and stormy marriage of Ernesto Vargas and Dora Llosa left a lasting mark on their only son, Mario Vargas Llosa. The writer’s parents separated five and a half months after their marriage, before the child was even born. Little Mario grew up with his maternal family, believing his father was dead. Much later, when he already had gray hair, the Nobel Prize winner understood the reason for his parents’ failed marriage: resentment and social complex. “Because Ernesto Vargas, despite his white skin, his light eyes, and his handsome figure, belonged — or felt that he belonged, which is the same thing — to a family socially inferior to that of his wife,” he revealed in his memoirs, A Fish in the Water, published in 1993.

Given this background, it’s no surprise that Vargas Llosa sought love within his own family. In 1955, at the age of 19, he met Julia Urquidi, the sister of his aunt Olga, whom he had known since childhood. “Aunt” Julia, as he called her, was 12 years older than him, had recently divorced, and was visiting Lima to spend a few weeks on vacation with her family. The writer, who was in his third year of university, fell in love with this mature woman with a tall, graceful figure, a husky voice, and a hearty laugh.

The couple kept their affair a secret for several months. When the family found out, Ernesto Vargas threatened to shoot his son and urged him to resolve the situation. Young Mario, who had just published some stories in literary magazines, concluded that he had to legalize his relationship with Urquidi. Aunt and nephew eloped and married in secret in the town of Grocio Prado, on the Peruvian coast. The mayor of Grocio, a fisherman, and a local resident served as impromptu witnesses. The newlyweds, without money or support from their relatives, celebrated the wedding with a toast of Coca-Colas.

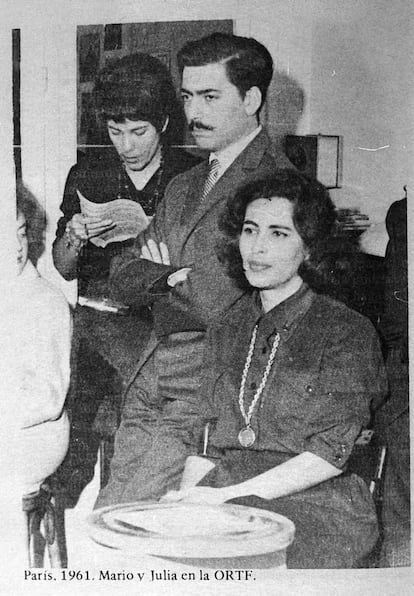

Back in Lima, the Vargas and Llosa families tried to separate them. The couple moved to Paris, where he continued studying and writing. He then began to wonder if his marriage had been hasty. “Not because Julia and I didn’t get along well, for we had no more disputes than any ordinary married couple, and the truth is that Julia helped me with my work and, instead of hindering it, encouraged my literary vocation. But because that initial passion had faded and had been replaced by a domestic routine and an obligation that, at times, I began to feel like slavery,” the writer would recall in his memoirs. “Time, instead of narrowing the age gap, would dramatize it until our relationship became artificial.”

His predictions ended up coming true. The romantic union ended up falling apart in 1961 when Vargas Llosa met his cousin, Patricia Llosa Urquidi, daughter of his aunt and uncle, Lucho and Olga, in Paris. He was 25 and finishing his first novel, The Time of the Hero, and she was just 16 and taking French culture courses at the Sorbonne. Patricia and her sister, Wanda spent a year at the home of Vargas Llosa and Julia Urquidi in the area of the Military School, on the Champ de Mars.

Less than three years later, the writer separated from “Aunt” Julia to marry his cousin Patricia. The story of this affair has two literary versions. In 1977, Vargas Llosa published Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, a novel inspired by his own love story. In 1983, “Aunt” Julia responded with What Varguitas Didn’t Say, a confessional story that portrayed the misfortunes of life together with an incorrigible womanizer.

“These stories happen every day, all over the world. I have not been the only one, the first, nor will I be the last woman who has lived between heaven and hell in an attempt to save a love that existed only for her,” Urquidi stated about her book.

Vargas Llosa explained: “Of course, in both stories there are more inventions, misrepresentations, and exaggerations than memories, and when writing them, I never intended to be anecdotally faithful to events and people that occurred before and were unrelated to the novel.”

He added: “In both cases, as with everything I have written, I started from experiences that are still vivid in my memory and stimulating to my imagination, and I fantasized about something that reflects those working materials in a very unfaithful way. Novels are not written to tell the story of life, but to transform it, adding something to it.”

Mario Vargas and Patricia Llosa ended up marrying and spent their first years in Paris, where they befriended Chilean writer and diplomat Jorge Edwards, Lima-born narrator Julio Ramón Ribeyro, guerrilla fighter Pablo Escobar, and members of the Latin American Gauche Divine of the time. They had three children: Álvaro, born in 1966; Gonzalo, in 1967; and Morgana, in 1974. The marriage had its ups and downs. Two years after Morgana’s birth, Vargas Llosa had a heated argument with his friend Gabriel García Márquez. Neither of them explained the reason, but those close to the Nobel Prize winner suggest that Patricia could have been the reason.

At the Nobel Prize ceremony in 2010, Vargas Llosa wept with emotion when he mentioned his cousin and wife. “Peru is Patricia, the cousin with the pert little nose and indomitable character whom I was fortunate enough to marry 45 years ago,” he said, his voice breaking. “Without her, my life would have dissolved long ago into a chaotic whirlwind, and Álvaro, Gonzalo, Morgana, and my six grandchildren would never have been born,” he added. “She does everything, and she does everything well. She solves problems, manages the family economy, brings order to chaos, keeps journalists and intruders at bay, defends my time, decides appointments and trips, packs and unpacks my suitcases, and is so generous that, when she thinks she’s scolding me, she is paying me the highest compliment.”

In May 2015, they gathered their entire family in New York to toast their golden anniversary. A few days later, ¡Hola! magazine published photos of the Nobel Prize winner with Isabel Preysler, a Spanish socialite and old friend he had met in 1986 when she interviewed him for the gossip magazine. [In the 1970s, Preysler was married to the popular Spanish crooner Julio Iglesias, whom she had also interviewed while working as a reporter for ¡Hola!. They are the parents of the singer Enrique Iglesias.]

“Photographed together at a lunch for two in Madrid,” the gossip magazine headlined. The report stated that the Vargas Llosa couple had separated. Patricia issued a statement saying: “My children and I are surprised and deeply saddened by the photos that appeared in a gossip magazine. Just a week ago, we were with the entire family in New York, celebrating our 50th wedding anniversary and the awarding of the doctorate from Princeton University. We ask that you respect our privacy.”

Days later, ¡Hola! published new photos of Vargas Llosa and Preysler that confirmed their relationship. “This is a relationship born of infidelity,” declared Gonzalo Vargas Llosa, the writer’s son. The novelist’s relationship with the socialite distanced him from his family and brought him closer to the world of glossy magazines, a world he had strongly criticized in his essay, The Civilization of the Spectacle, published in 2012.

Vargas Llosa, who had denounced the trivialization of the arts and literature and the triumph of sensationalist and frivolous journalism, was now one of its leading figures. “Do you know how many copies ¡Hola! sells in Spain each week? A million,” he said during the press conference for his novel The Neighborhood. “What wouldn’t a novelist give for a million magazine readers... ¡Hola! is a cultural phenomenon of our time. It offers a pink slice of life. In it, everyone is rich, everyone is happy, everyone participates in activities that bring pleasure. There are millions of people who want that material that makes them dream. Before, it was novels that offered that.”

His high-profile relationship with Preysler, punctuated by appearances at photocalls, parties hosted by the ceramic tiles company Porcelanosa, and even on a local reality show, threatened to tarnish his literary prestige. But what began as a scandal ended the same way. After eight years of dating, ¡Hola! announced their separation. The magazine reported that the socialite had left him due to jealousy. His entourage claimed that they were “incompatible.” “He’s interested in culture, and she’s interested in show business,” they noted. Preysler said the breakup didn’t hurt her at all. Vargas Llosa told EL PAÍS at the time that he didn’t regret anything, but acknowledged that they were from two different worlds.

Vargas Llosa once again found support and companionship in his cousin Patricia, “the cousin with the upturned nose and indomitable character” with whom he had fallen in love more than half a century earlier. He dedicated his latest novel to her, Le dedico mi silencio, published in 2023. “It’s a beautiful and well-deserved gesture,” the writer’s entourage told EL PAÍS, declining to label the relationship. “It’s not for us to say whether this relationship is romantic, but the important thing is that the family, which had been estranged for seven years, is united again,” they added. Vargas Llosa died at his home in Lima, accompanied by his cousin Patricia and their children.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.