When Mario Vargas Llosa punched Gabriel García Márquez

The writer Jaime Bayly novels the blow that broke the friendship between the Nobel Prize winners

“That book will be a bunch of lies,” Mario Vargas Llosa told EL PAÍS a few weeks ago, when asked about the imminent publication of Los genios (“The Geniuses”), by Peruvian writer Jaime Bayly.

This past Wednesday, March 22, in the aristocratic Wellington Hotel in Madrid, Bayly corroborated this remark.

“Yes, it’s full of lies – like every novel – but [there are] no capricious or whimsical lies… only credible ones.”

The geniuses are Vargas Llosa and García Márquez – and the book is the novel about the end of their friendship. But the book’s prologue starts with a warning from Bayly:

“This book is not a historical text or a journalistic investigation. It is a novel, a work of fiction, which mixes real, historical events with fictitious events that come from the author’s inventiveness.”

Bayly tells this newspaper that “it’s not a historical text, but it is a historical novel; and it’s not a journalistic chronicle, but it’s a novel that I have investigated from a place of journalistic curiosity… let’s say, from my [position] as a journalist.”

At the start of the novel, Bayly legitimizes this kind of genre by quoting a line from the novel Historia de Mayta (“The real life of Alejandro Mayta”), published by Vargas Llosa in 1984: “Something that is learned trying to reconstruct an event based on testimonies is precisely that all the stories are tales… [and] that they are made up of truths and lies.”

This is followed by the first line of the book – the words that Vargas Llosa allegedly shouted at Gabriel García Márquez before punching him at a Mexico City movie theater in 1976: “This is because of what you did to Patricia!”

“He said ‘because of what you did to her’ – not ‘because of what you told her,’ as some have said,” says Bayly, who claims to have spoken with a person who was there.

What happened that day has never been confirmed. No one can say for sure if García Márquez did or said something to Patricia Llosa. The Colombian Nobel Prize winner died in 2014 without revealing it. The Peruvian Nobel Prize winner, at 86, has not and has no plans to do so.

Manuel Jabois, in a recent interview in EL PAÍS, asked him again what could have broken their relationship. Vargas Llosa replied: “Women, simply.”

Bayly asked the two men the same question in the past. When he queried García Márquez, in Washington DC in the 1990s, he told Bayly, “I didn’t fight with [Vargas Llosa]... he fought with me. And I’m not going to tell you anything else. Talk to my friends.”

Aboard Vargas Llosa’s BMW in Lima, in 1985, the novelist told Bayly, in a very serious tone, that he was “never going to talk about that subject.” He also noted that “García Márquez has cancer.”

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Bayly notes. “Gabo (the author’s nickname) still lived for 30 more years.”

The secrecy around the mythical punch – reflected in a famous photo of García Márquez with a black eye – always seemed “very literary” to Bayly. It motivated him to go through the story, using a mix of fable and facts.

“When two geniuses refuse to talk about something like that, man, they’ve piqued your literary curiosity! Because I understand literature as opening the closet to see what skeletons are inside.”

Bayly affirms that the work is based on documentation and a collection of testimonies that date back to the 1990s. In the bibliography, he cites the biographies of García Márquez and, above all, the encyclopedic Aquellos años del boom (“The years of the Latin American Boom”), by Xavi Ayén.

The book includes testimonies from writers such as Jorge Edwards, Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, Tomás Eloy Martínez and Álvaro Mutis, as well as an account from Carmen Balcells, who served as the literary agent to the two Nobel Prize winners. Bayly describes her as more intelligent than the two of them put together: “A supernatural creature, a hurricane of noble winds, inventor and tamer of all geniuses.”

The accumulated knowledge allows him to carry out a rich psychological and contextual profile of Mario and Gabriel in the nine years that their friendship lasted. More specifically, he probes the phase that interests him the most: the two years prior to the punch.

During this time – according to the book – Vargas Llosa left his wife, Patricia, for another woman.

“What happens between Patricia and Gabo at that moment… therein lies the secret of the novel. What’s more, what happens between Patricia and the gabos [Gabriel and his wife, Mercedes Barcha, who died in 2020]. What did the gabos say to her? How did Don Gabriel make a pass at Patricia… if he even did at all? What happened between them?”

In the novel, Bayly offers a conclusion. We will not reveal it, except to say that it is quite mild compared to what could be expected from the author, an enfant terrible of the Lima elite, who, after many wild years and scandalous novels, is more tame today.

But the important thing about the book is not how it resolves gossip. The value of this historical novel is how it illuminates an event that transcended everything – that is, the brotherly friendship of two literary giants, which ended in ruin.

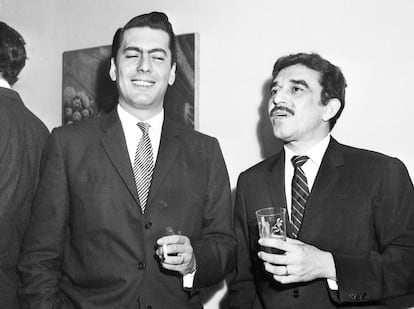

The book offers valuable information. Even the cover photo of the two men is rare – Bayly found it in the archives of the Peruvian magazine Caretas and bought it. A few weeks before it was taken, in 1967, they had met in Caracas, before traveling to Lima to give a conference. Both wear suits and ties – Mario holds a cigarette and, from his height, looks down at Gabriel from the corner of his eye. The Colombian – who had just published One Hundred Years of Solitude – looks comfortable... but not as comfortable as he would be in 1982, when, dressed in a white guayabera, he would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“In this photo, Gabo wanted to be as successful as Mario already was. A year later, the roles had already switched,” says Bayly, alluding to the vast commercial success of Gabo’s novel of magical realism. By 1967, the two men had read each other and expressed their mutual literary admiration.

In the following years, a relationship of great affection and intimacy developed. They were neighbors in Barcelona from 1970 to 1974: Mercedes and Gabriel, Mario and Patricia. Bayly counted the steps between doorways…. he didn’t reach a hundred. He says that García Márquez called Vargas Llosa “brother.”

The Peruvian admired him, he says, “for his prodigious imagination.” The Colombian esteemed Vargas Llosa’s “intellectual head.” The 1970s were not, however, creative times for either man.

“Vargas Llosa only published one minor novel – Captain Pantoja and the Special Service – and García Márquez didn’t publish anything again until 1975, The Autumn of the Patriarch. I think the success of One Hundred Years of Solitude seized them both. Gabo didn’t know what to do to live up to what he had done… and Mario didn’t know what he was going to do to beat him, like he had always beaten him before, if not in sales at least in terms of criticism.”

The fistfight ended their friendship, since they never spoke or saw each other again. But in light of Bayly’s work and the creative chronology of both men, it could be said that the fight was an excellent literary decision. Following the black eye, they unlocked themselves creatively. García Márquez would get the Nobel Prize in 1982, while Vargas Llosa would receive it in 2010.

Balcells, says the author of The Geniuses, tried to reconcile them. Gabo was willing. “In his last decade of life, García Márquez waited for him twice… once in Barcelona and once in Cartagena. But, in the end, Mario never showed up.”

When asked why he thought his compatriot would have done that, Bayly replies thoughtfully: “Because I think he’s a man who is very loyal to his friends… and even more loyal to his enemies.”

The men followed their glorious paths accompanied by their wives. Gabo with Mercedes – his highest authority – and Mario with Patricia, his wife and first cousin, who, in the novel, forgives him for his infidelity and returns to him.

“You have to have a lot of character, intelligence and wisdom for that,” says Jaime Bayly. “In The Geniuses, she is the underrated genius.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.