Yoruba, Kimbundu and Kikongo: How African languages shaped Brazilian Portuguese

Heritage pride in the samba schools of Rio de Janeiro is just one important symbol of a 3,000-plus-word legacy that is still subject to stigma

“Excess of words in Yoruba” was the justification used by a member of a judging panel at Rio de Janeiro’s Carnaval to dock points from a samba school. The group Unidos de Padre Miguel had put together a parade that paid homage to the origins of Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian faith, complete with a song full of words with African roots.

The evaluation ignited powerful debate, and even Culture Minister Margareth Menezes weighed in. “It is disrespect to our ancestry, samba was born from resistance,” she said.

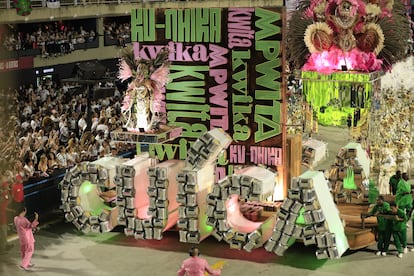

Nearly all samba schools celebrate Brazil’s African heritage in one way or another. Mangueira used its parade to praise Bantu culture, with many of its members wearing costumes honoring the African vocabulary that has long been integrated into Brazilian Portuguese. This is no minor contribution, but rather a 3,000-word lexicon inherited from the nearly five million Africans who, after being kidnapped and enslaved, arrived in Brazil between the 16th and late 19th centuries.

This linguistic diversity, despite all possible prohibitions and barriers, wound up molding the Portuguese that is spoken in Brazil today. Nor is its impact is limited to vocabulary; African heritage has left its mark on pronunciation, syntax and grammar.

The primary languages that survive in Brazil are Yoruba, Fon, Kimbundu and Kikongo, the last two hailing from the Bantu linguistic group, which is has had the greatest influence on modern-day speech. They belong to different ethnic groups from sub-Saharan Africa, the inhabitants of the lands that today are known as Nigeria, Benin, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. Once enslaved, their speakers were forced to abandon their mother tongues, and for good measure, slave owners would place members of different communities together in order to prevent them from communicating with each other.

Many words survived in private, and due to this, it’s no coincidence that the majority have to do with Candomblé and other African faiths, as well as food. Acarajé, which refers to a spicy empanada that has become the gastronomic emblem of the state of Bahia, is a Yoruba world that literally means “to eat a ball of fire.”

Culinary examples are numerous, as are those related to music and with the Orishas and rituals practiced in terreiros (ceremonial spaces). Nowadays, these hidden places, as well as quilombos, the communities formed by the descendants of those who came from Africa that are largely located in rural areas, are the last bastions in which the languages that came from the continent can be heard.

Still, many words have made the leap from spaces of Black resistance and are now used in everyday Brazilian life, by members of all racial groups, who are often unaware of their origin. Going to the beach to take a dip in one’s thong or sunga (men’s swimming briefs) and sunbathing on a canga (sarong) requires the use of African words. So do samba and the chachaça (distilled spirit) used in the cocktail cairpirinha, as well as terms less easily translated, like cafuné (an affectionate head caress).

Many of these African words wound up taking the place of those that came from Portugal on the caravel sailing ships. To speak of the youngest member of the family, the Portuguese say benjamin; Brazilians, caçula. In Lisbon, during nap time, they dormitam, but in Rio, they take a cochilo. The list is long and has led the intellectual Lélia Gonzalaz, a leader in the Black Brazilian movement, to declare that Brazil doesn’t speak Portuguese, but rather, Pretugués (from preto, a word for Black).

Many of the historical prejudices against the African influence on Brazilian Portuguese are related to a lack of written records and the difficulty that academia has had in addressing the complexity of oral cultures. One of the few documents that have proved helpful in codifying linguistic history has been a Kimbundu grammar book published in 1697 by the priest Pedro Dias. The booklet, which is less than 50 pages long, is titled Arte da Língua de Angola, and was designed to be used by the Jesuits so that they could more easily preach to the enslaved individuals who had recently arrived from the western coast of Africa.

For Federal University of Bahia African linguistics professor Wânia Miranda Araújo da Silva, the lack of records is “one of the greatest challenges” to the social pedagogy that must be constructed in order to place proper value on the oral knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation, above all in traditional communities. It’s the only way to be able to demonstrate that there has been a notable impact that goes beyond lexicon.

Indeed, intonation, the way in which some phonemes are pronounced, the tendency to place vowels where there are none (as opposed to Portuguese in Portugal, which is highly consonantal) and the double negative (não vou não, literally “I am not going no”) are all vestiges of Africanness in the speech of Brazilians, she explains in a phone interview.

These are factors, says Araújo, that add tension to the ever-complicated relationship with language purists, especially in the homeland of Luís de Camões. “With Portugal there is tension, we have an orthographic agreement between the countries that speak Portuguese, but the linguistic emancipation between Brazil and Portugal took place long ago, on various levels,” she says.

There are more and more programs of study at Brazilian universities that, instead of looking to Portugal, prefer to delve into the similarities of Brazilian Portuguese with the Angola language of Mozambique, for example. But at the institutional level, there is still much to be done.

Despite the fact that in Brazil, hundreds of languages are spoken (largely due to diverse Indigenous communities), it is still seen as a monolingual country, says Araújo. The closest the country has to a public policy to properly value African languages is a law passed in 2003 that requires public schools to teach Afro-Brazilian history and culture, though it is hardly ever enforced.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.