Leni Rienfenstahl, ‘Sun and Shadow’: Hitler’s filmmaker stripped bare in new documentary

German filmmaker Andres Veiel reexamines the figure of the director of ‘Triumph of the Will’ and ‘Olympia’ through her extensive and valuable private archives

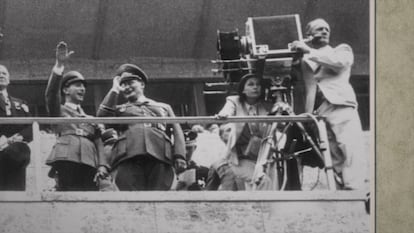

Leni Riefenstahl (1902-2003) dreamed of making a documentary that would be on a par with those she had made in the 1930s for Adolf Hitler. The tyrant and mass murderer had been dead for several years, and the filmmaker of the admired and disturbing Triumph of the Will and Olympia had been exonerated by the new authorities despite her obvious involvement with National Socialism, but she was unable to secure projects up to par with those she had directed during the height of National Socialism.

She found inspiration during a trip to several Spanish cities in the 1950s. “Spain, the country of the greatest contrasts, like its history, knows no measure,” she wrote in a document about this project that was never realized. “We are conquered by its radiant joy, oppressed by its inexorable severity, fascinated by its mysterious soul. Whoever has felt the wonderful pulse of this country once, will forever be devoted to it.” “It will consume you in an endless nostalgia, until you can return to it again and again. In this film, I want to retain this mystical charm on celluloid.”

The 20-odd pages in German and Spanish about the documentary, which was to be titled Sun and Shadow, are part of the 700 boxes of archives that Riefenstahl left to the Berlin-based public foundation Preußischer Kulturbesitz when she died. The boxes are the basis for Riefenstahl, a documentary by Andres Veiel produced by the well-known journalist Sandra Maischberger and released in Germany last autumn, where it was seen by 120,574 people. .

In October, the publisher S. Fischer will publish Close-up Leni Riefenstahl. Neue Perspektive aus dem Nachlass (Close-up Leni Riefenstahl. New Perspectives from her Archives) in German. The vast quantity of objects and documents — film reels, audio recordings, letters, personal notes, documentaries such as Sun and Shadow — contain everything that Riefenstahl wanted to leave to the world. And they lay bare, perhaps unintentionally, the personality of someone who desperately sought the spotlight until the very end, and an ideology that, despite her attempts to gloss over the past, she apparently never renounced in private.

Riefenstahl brings to light recordings of phone calls from Riefenstahl admirers and Nazi nostalgics in 1970s West Germany. She complains about being linked to National Socialism and claims: “I am not responsible for what happened!” One interlocutor tells her that it will take “one or two generations” until “morality, decency, tradition, and good manners return,” to which the filmmaker replies: “The German people have the conditions to achieve this.”

There are disturbing moments, such as the outbursts of anger when, during an interview, she is asked about her relationship with Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister. And seemingly banal but revealing dialogues, such as those she has with Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect. It is the late 1970s, they have known each other since the days of the Third Reich, the architect has been released from prison and has enjoyed success with his memoirs, cultivating the image of the good, sophisticated Nazi. Speer asks Riefenstahl how much she charges for her lectures, while she seeks advice on writing her memoirs.

Veiel, the director of documentaries such as Black Box BRD and Beuys, lists three surprises that he discovered during his meticulous examination of Riefenstahl’s archives. The first, he says, are the documents about her childhood and the violent upbringing her father subjected her to, “the original genes of fascism.” The second is the aforementioned telephone calls, which, according to the documentary maker, clearly show that she “never distanced herself from this ideology,” and reveal a whole atmosphere of Nazi sycophancy hidden in the Federal Republic. The third is a letter signed by a German soldier indicating that Riefenstahl was possibly a witness to a massacre of Jews in Poland at the beginning of the war, and may even have played a role in the episode.

Riefenstahl was covering the conflict as a documentary filmmaker, and according to the letter, before filming a scene in the square in the town of Końskie, she ordered: “Get the Jews out of here.” The order caused panic, the Jews who were there tried to flee, and the Germans opened fire. “This is not historical evidence,” says Veiel. “The person who describes it in the letter is a non-commissioned officer. There is no other evidence. But at least it is plausible.”

Riefenstahl, as Veiel documents, spent the entire postwar period denying that she knew anything about Nazi Germany’s crimes and claiming that she was interested in pure art, the aesthetics of images, and not politics. One criticism of the film has been that it did not sufficiently highlight Riefenstahl’s contradictions and responsibilities in the impressive films about the NSDAP congress in Nuremberg in 1934, or the Berlin Olympics in 1936. Veiel chose another path: to show rather than explain. At one point, Riefenstahl appears commenting with emotion on images from Triumph of the Will, and claims that the film only highlighted peace and work, but Veiel then introduces a speech taken from the same film in which a Nazi leader talks about “race” and “people.” “At first I thought that I had to contradict her, that I had to show that she was lying and how she was lying,” says Veiel. “But the deeper we looked into her legacy, the easier it became, because she contradicted herself.”

Was she a brilliant filmmaker ahead of her time? An opportunist? A convinced Nazi? Everyone from Andy Warhol to Quentin Tarantino, including Francis Ford Coppola, has praised her work. Her influence can be seen in everything from Star Wars to any sports broadcast and, of course, Olympic ceremonies. “She was a good editor, a good montage maker, a good director,” says Veiel, “but aesthetics and ideology cannot be separated.” In her later years, Riefenstahl presented herself as a victim of those who questioned her about her past. The paradox is that she complained about being constantly linked to Hitler, but at the same time she knew that it was what attracted the television cameras and interviewers: the fascination of getting close to Hitler’s filmmaker. The Führer, in addition to her unquestionable talent, was her lure.

There is no mention of Sun and Shadow in Riefenstahl, but it is tempting to imagine how it would have reflected Franco’s Spain. “[The] relationship [of the Spanish man] with the Virgin is as universal as it can hardly be in any other country in the world. You have to know this to understand that even today it would be unimaginable for a Spaniard from a good family to marry a girl who is not a young woman,” she writes, and alludes to Olympia, the documentary about Berlin 1936, as a model.

“I would like to make my film about Spain in a similar way,” she says. Sun and Shadow was expected to cost 355,000 German marks at the time. In her memoirs, she wrote that she threw in the towel when she saw the complications involved in production: “I was so disappointed that I no longer wanted to deal with Spanish projects. I had been made many promises, and I had worked hard for nothing. Since then, such projects have lain untouched in my archives.” Buried until now.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.