Lisa Tuttle, history-making science fiction and horror scribe: ‘Life is hard, but a zombie apocalypse is harder’

The 72-year-old writer has always been ahead of her time when it comes to sexuality, feminism and gender identity in the world of fantasy literature

For many readers, Lisa Tuttle’s name is inextricably linked to that of George R. R. Martin, the author of Game of Thrones, with whom she was in a romantic relationship with in her twenties. And more specifically, to the beauty that is Windhaven, an imaginative and sensitive novel that the two wrote together. It’s a story about a girl on an ocean planet with islands inhabited by the descendants of a crashed colonial spacecraft. The population stays in contact via the flyers, who pass down precious wings made of lightweight metal from generation to generation.

But of course, Tuttle, 72, is much, much more than Windhaven. A writer in possession of an exceptional talent for telling wondrous and unsettling tales, who has penned a handful of novels (among them the award-winning Lost Futures) and short stories, a format in which is a true master. She works in horror, weird fiction and dark fantasy, as in her collection Memories of the Body: Tales of Desire and Transformation, vignettes that remain buried in one’s memory like the first glimpse of an exotic plant.

Tuttle, who lives in the Scottish village of Torinturk, was in Barcelona for the latest edition of the Fantasy Genres Festival 42, which took place on November 10. She participated in several of its events, including roundtables on both European fantasy and the contemporary love of being scared. She is a charming woman with a fascinating perspective on modern fantasy and has been a pioneer of issues related to sex, gender identity and feminism — these efforts are not limited to fiction. She also penned Encyclopedia of Feminism in 1986.

On the day of our interview, she was clad in a shirt with a bird print, which leads us to talking about Windhaven and flying as she sips a Coke in the bar of her hotel as Moonlight Shadow plays in the background. Wouldn’t you know it, the Mike Olfield song was inspired by Houdini’s death and attempts to contact the escape artist via mediums. The number seems quite in keeping with Tuttle’s own recurring trope of ghosts. The writer is a great admirer of M.R. James, author of The Spirit Cabinet.

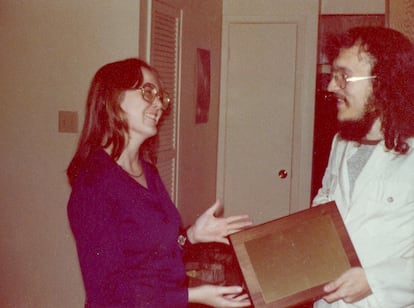

“So George and I were two novice writers, both of us had had a few stories published,” remembers Tuttle as she recalls how Windhaven came to be. “We had met a few months before, at a writer’s conference in Dallas in the summer of 1973. I was 20 years old and George, 24, and he proposed that we write something together. He had a lot of seed ideas, as he called them, that he wanted to develop. That’s how the story of The Storms of Windhaven was born. We published it in 1974 and then expanded it until it became the Windhaven novel.”

She continues: “It was about a colonial spaceship that crashes on a planet and its occupants create a medieval society that has lost all knowledge of technology, except for the wings they made with metal that was scavenged from the spacecraft and that allow their owner to become a glamorous flyer. The conflict comes about when a girl who is not entitled to fly, because the flyers form a caste with rigid codes, is obstinate in owning wings and using them.”

The descriptions of the freedom this flight provides are beautiful. “Well, neither George nor I had any experience of flying. I remember he even took me up a mountain once and said, ‘Can you imagine, Lisa, this is where our winged ones would launch.’ The story worked very well and Ben Bova, the publisher of Analog, asked us to expand it. We wrote two more parts and all three were published as Windhaven in 1981. It was George’s second novel after Dying of the Light and my first. We often talked about writing a sequel, but time took each of us in a completely different direction. We were a couple then, but we called it quits. George says I broke his heart. He got married, then so did I [to writer Christopher Priest, author of The Prestige, in 1981 and settled in London; then, in 1990 she married again, to her current partner, publisher Colin Murray]. But we have always remained good friends. George is a very loyal person.”

Did she ever think of making a film adaptation of Windhaven? “No, and it’s a shame because it would have worked well, but they hadn’t developed the special effects they have today. It was difficult to make someone fly. You have to remember that Superman didn’t fly on screen until 1978.”

Martin’s experience with Game of Thrones has been a curious case. The hit HBO show was completed before his novels, he hasn’t yet finished the story, and there are fans who troll him for it. “It’s been sad in some ways, but also great business. George has a melancholy side, but success and money make things easier. How you experience them depends on your personality; however, having a private jet, or being able to have one, helps. In the world we came from, the idea that a science fiction, fantasy or horror book would be a bestseller seemed ridiculous. That perception has changed, of course,” says Tuttle.

Tuttle likes fantasy genres because they allow for the exploration of ideas that reject “the fantasy of kingdoms and worlds that establish a Manichean difference between light and darkness.” She agrees with the general consensus at Festival 42 about how “there is more horror than ever” today in popular culture.

“It’s more pervasive and varied than it has even been, both as a genre — if it is really a single genre, considering the differences between subtle ghost stories, graphic body horror, psychological horror and weird fiction, to name a few variants — and in the sense that it is a component of all literature,” she says. “It’s more popular because, while the situation in the world today is no worse than at other times in the past, we are now aware 24 hours a day of horrors happening everywhere, through the media and social networks.”

Tuttle believes that we turn horror into entertainment for several reasons. “Life may be hard, but at least it’s not as hard as a zombie apocalypse. Horror stimulates empathy with others as well as provoking fear. It produces catharsis (the classic response!), helps prepare us to deal with terrible situations in the real world, making you more resilient; and it reactivates your emotions when you feel beaten down or overwhelmed by real life and the daily struggle.”

She thinks that in general, her work is closer to horror than science fiction. “I like how science fiction makes you think, its more intellectual side, the sci-fi that has to do with ideas, the kind that forces you to interrogate yourself and question things. The side that makes you think about gender, or about immortality, about finding beings who have values other than our own, as in Lost Futures, parallel universes in which one can rectify mistakes. But yes, what I write is more in the field of horror or dark fantasy.”

She continues: “Even though I don’t like horror movies and certainly don’t like gore. My area is rather to make you feel a vague and subtle discomfort, the psychological side of horror. The irruption of the unthinkable, the dream, the nightmare. Bringing a different perspective to our world. I hate zombies — well, they bore me, they don’t interest me, I don’t see the point. I am interested in anthropological zombies, those of voodoo, those of Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie, the ones which have to do with slavery, subjection to another. But not zombies who eat brains. A zombie novel I like is It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over by Anne Marcken, which won the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction this year.”

The presence of Le Guin can be felt in some of Tuttle’s stories, such as The Wound, the shocking story of a professor who starts to turn into a woman and bleed when he meets another man. Did Tuttle know the author of The Left Hand of Darkness? “I admire her very much. I still remember the impact that The Dispossessed had on me. She tutored me in a writing course.”

Tuttle’s story Lizard Lust is one of her tales that remain inscribed on a reader’s memory, like J.G. Ballard’s The Delta at Sunset or Philip K. Dick’s The King of the Elves. It is also reminiscent of Le Guin’s work. In Tuttle’s story (which contains the anthological phrase “this is what happened between me and the lizard”), the possession of a lizard determines people’s gender and turns women into violent men.

“I’m very proud of that story, which sometimes goes unnoticed. The idea came to me from something I read by Freud. I was reflecting on the concept of the phallic symbol and the way things like guns and cars are perceived in that manner, even though they may not look anything like a human penis. I was thinking about how, supposedly, all women suffer from penis envy because possession of one implies having a special power that has always been denied to those who don’t have one,” she says.

“Well, Freud wrote that although in dreams, a cigar may be a phallic symbol, sometimes a cigar is a cigar. From there — I can’t remember what exactly my line of thinking was — I imagined a group of people dividing themselves into two genders, even though there was no differentiating biological sex marker such as a penis. Instead, they found another way to claim that one group was superior to the other: they were the only ones who possessed something, and I decided that this would be a small creature. That creature was their power. Why did I decide to make it a lizard? It seems natural: something small, the size of a cigar, likely harmless, though it has the possibility of being dangerous, and so absurd. The idea that, by having a lizard in your pocket you could inspire envy and fear in the lizardless, who would do anything to be near you and your reptile. It made me laugh.”

And while we’re on the subject of lizards, what about dragons? They’re long been the official mascot of Festival 42. “I ask myself if they play the same role, on a gigantic scale, as the lizards in Lust Lizard. They have to do with sex and power, or sex as power. Can you imagine riding and being able to control the power of a huge flying, fire-breathing beast? And not necessarily a male beast. It’s something I wrote about in my story The Dragon’s Bride. Jung described the dragon as an archetypal female image. He said it represented the devouring aspect of the mother. By slaying the dragon in the old stories, the hero liberates himself.”

Another Tuttle story that is difficult to get out of your head is Bits and Pieces, in which a woman collects pieces of her lovers’ bodies. “I started thinking about how people leave their lighters and keys in their lovers’ homes, and I decided to go a little further and have them leave pieces of themselves behind. The protagonist, Fay, puts them together, Frankenstein-like, to create a perfect lover.”

The story, written in 1990, features a harrowing passage in which Fay wants to halt a sexual encounter and her lover ends up raping her, with the excuse that it’s what she actually wants. “No means no” comes to mind, though the piece was penned long before the issue of consent was mainstream. “Feminists have been saying it since the 1980s. It has long been pretended, in the justifications of rape, that women have fantasies about [rape], and the scene in which my character is violated alludes to that falsehood.”

She reflects that: “Today’s feminism is different from that of my time, the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s. Back then, I never would have thought that it would take so long to achieve the things we fought for during those years. But fortunately, in the end, the fight for rights and against male sexual assault has achieved some success (as shown by the #MeToo movement) and hopefully, the ground gained will not be lost, but will continue to grow. Certainly, younger people of both sexes seem to see the world differently, not so divided into two (often, opposite) genders. I am in favor of more gender diversity and recognition, of course, but it is possible that some of my views could be seen as old-fashioned today, and I am not actively involved in any movement. I think at present, talking about feminisms, plural rather than singular, is a better way to look at things.”

One of the most famous anecdotes about Tuttle is about her rejection of the 1981 Nebula Award, an honor imparted by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association. She made her decision to withdraw her story The Bone Flute from the running after another candidate sent his work to a jury member, which she found inappropriate. Her piece still won, and was given to her despite her formal dissent.

Tuttle has always spoken highly of Ray Bradbury. “He had a large influence on my writing when I was young. He was one of the first science fiction authors I read and I adored his short stories, especially The Martin Chronicles. I read them and re-read them beginning from when I was 13 years old, when I decided that it was how I wanted to write. I only saw him one time, in 1973. At that time, I was at Harlan Ellison’s house in Los Angeles and one day, Harlan had to give a talk at a school with Ray Bradbury — who he had to pick up because of course, Bradbury never learned to drive — and he asked me if I wanted to go.

“What, and meet one of my favorite writers? Of course! At that point, I only had a handful of stories published, but those two famous writers introduced me to the professors and students as if I was their colleague. I remember that it was the first time someone asked me for an autograph. Somewhere out there, somebody who was a student at that school has my signature alongside those of Harlan Ellison and Ray Bradbury. I remember that Ray (he made me call him that and not Mr. Bradbury) was charming, a wonderful and enthusiastic person who spoke about writing and reading and things he loved.”

When asked about Donald Trump’s win, Tuttle’s hands fly to her head: “It’s horrible, horrible, horrible! He is a completely inadequate man to be president, and he’s dangerous. We had gotten so excited about the arrival of the first woman president.”

The author remembers that the first time Trump was elected in 2016, she was in Barcelona. And, she recalls that years before that, in 1990, she took part in the same city’s International Feminist Book Fair, which her admired Angela Carter also attended. Her first trip to Barcelona was as a young woman in 1972, on a trip to Spain with a friend who had family in the Madrid town Torrejón de Ardoz. “I remember that dark country. How it has changed,” she says.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.