Canada, a laboratory for the decolonization of museums

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is unveiling a new gallery to showcase its collection of Inuit art, adding to other initiatives in defense of the country’s indigenous artists

The Irish historian and political scientist Benedict Anderson used to say that nations are social constructs, communities imagined by individuals who feel part of the same group. In Canada, for more than a century, one of the primary functions of museums was to contribute to the consolidation of these constructs, participating in the creation of the national identity of a young country. But for decades, the process omitted the legacy of the First Nations, the Inuit, the Métis and other indigenous peoples whose lands were taken by European settlers and who successive Canadian governments marginalized and massacred. In recent years, as Canada tries to confront the darkest chapters of its history, its museums have begun a profound transformation, revising the imagined community they projected and following a path that some dare to call decolonization.

At the federal level, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa has been moving in this direction since the early 2000s, with measures such as the creation of a Curator of Indigenous Art in 2007, the merging of works by Indigenous and Canadian authors in the same gallery in 2017, and most recently the launch of a Department of Indigenous Ways and Decolonization in 2022, which has positively contributed to the diversity of the museum’s staff. At the regional level, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MBAM) has joined the trend with a series of initiatives, gestures and practices.

“We are working to be a multiperspectival and multivocal museum,” says director Stéphane Aquin. He says Greco-Roman art was once thought to be the foundation of culture and of the museum. “But by recognizing the presence of Indigenous peoples and their artistic practices in North America for thousands of years, we are undergoing a process of rebalancing,” explains Léuli Eshrāghi, curator of Indigenous arts at MBAM, a position created last summer that reflects the institution’s desire to embrace different points of view and opinions. “My role is to be attentive to artistic and design practices, cultural protocols, and Indigenous relationships. My goal is to make the space more welcoming to local and global Indigenous peoples. And yes, I am an art curator, but also something else,” explains Eshrāghi, who is descended from Samoan, Persian, and other groups.

Until a couple of decades ago, Indigenous art in Canada was relegated to ethnographic museums and sections devoted to crafts, separating it from fine art. And although the MBAM was a pioneer in the acquisition of Inuit art — in 1953 it started a collection that today encompasses almost 900 pieces by 300 creators — the works were scattered throughout the museum and in a small gallery located in a dark corner on the fourth floor of a building adjacent to the main one. When the center began to reconsider its way of presenting Inuit art five years ago, officials decided to hire a curator from these territories to give a new value to the collection. It took them two years to find Asinnajaq, a visual artist, writer, filmmaker and art curator from Inukjuak, an Inuit community in northern Quebec.

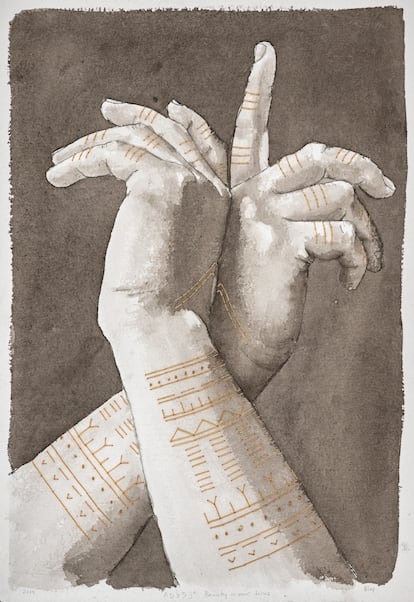

The first fruit of this collaboration was unveiled in early November: an exhibition of the museum’s Inuit art collection and some recent loans in a bright new space twice the size of the old gallery, which they have named ᐆᒻᒪᖁᑎᒃ uummaqutik: essence of life. For the next five years, 120 artworks by 70 Inuit artists will rotate through the gallery every four months, changing according to the season and the weather. “And the works will continue to do so,” says asinnajaq.

The curator says that the exhibition was conceived around the values of ingenuity, generosity, abundance and community, which serve as a common thread between the works of art and the space they occupy. In selecting and launching the project, asinnajaq relied on the complicity of Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, an Arctic anthropologist, art curator and Inuit researcher. “Krista was a kind of advisor to me, with whom I explored different cultural ways of operating and with whom I questioned some museum practices and curatorial practices in general. We went over everything: from the labels to the relationships with the artists and the team. What have we seen already? What would we like to see? What is appropriate in this context? How can we open up this space? How do we take care of the works of art?”

To begin with, asinnajaq wanted to break down the traditional distinction between arts and crafts: “For us, that fragmentation doesn’t exist; everything is art. In fact, many of the acquisitions and works on display could be included in a design exhibition. But I think they belong here. They are part of our culture and our artistic practices. This vindication is very important.” Once these barriers are overcome, the possibilities are endless: “We have glass, painting, textiles, ceramics, as well as the widely disseminated works on paper and carvings, and a much-talked-about motorcycle. It’s about making sure that we accompany people on a journey towards teaching art histories.”

The labels accompanying the works have also been the subject of debate and a break with the established order. “Usually, the information about the authors that museums include is limited to ‘born here and died there’. But this is not necessarily important to us, especially if you were taken by the government or the church. That is why we emphasize homelands and places of belonging, rather than places of birth,” explains asinnajaq, referring to the impact that boarding schools and the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families to place them in foster homes has on the way biographical data of Inuit artists is presented.

The names of some of the works, which were originally anonymous and given titles by historians and curators, have been revised to ensure that they are not culturally offensive or inappropriate. The curator says that those involved in the exhibition discussed “the autonomy and sovereignty of artists and the fact that their works do not have names. Often the names given are a bit banal and do nothing more than describe the pieces, but sometimes they are damaging…” The labels also include information about the work and the author in French, English and one of the Inuit dialects, which appears symbolically first.

This reconsideration, led by indigenous voices like asinnajaq, is not exclusive to MBAM but is part of the current process of transformation of Canadian cultural institutions. It is a change that involves the creation of spaces for dialogue, reconciliation and reparation to question this imagined, partial and distorted community, to whose creation museums contributed.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.