Flow States, the triennial that redefines Latinx art and its global history

The exhibition at the Museo del Barrio, in New York City, is presenting the work of 33 emerging and established artists. It includes figures who have never had a museum exhibition before, such as the 95-year-old Venezuelan clay artist Magdalena Suarez Frimkess

On the opening night of the second Latinx art triennial, New York’s Museo del Barrio welcomed 650 people over the course of four hours. This was a predictably high turnout, given that it’s one of the largest exhibitions of contemporary Latino art in the world. The first edition took place in 2021, in the midst of the pandemic.

The title of the triennial — Flow States — reflects the curatorial work carried out by María Elena Ortiz, Susanna Temkin and Rodrigo Moura to expand on the meaning of what’s considered “Latino,” going beyond a specific geography.

“[This exhibit considers] Latinx artists from an expansive perspective based on imperialist colonial history,” Ortiz notes. That’s why the exhibition also includes the work of Indigenous artists, such as Mario Martínez, as well as Filipinos, such as Norberto Roldán. The idea is to also show the complexity of the diaspora, by including artists whose mother tongue isn’t Spanish, but whose roots are Latino (as their names prove). This conceptualization reconnects various personal paths, which involve movement and can be very different from each other. Yet, what they have in common is the fact that, as metamorphosis takes place, individuals are exposed to vulnerability, exclusion and loss.

For two years, the curators conducted more than 80 studio visits to artists across the United States, but also beyond its borders. The result is a pluralistic and inclusive exhibition, which includes the work of promising young artists, such as Alina Pérez, Ser Serpas and Kathia St. Hilaire, all born in 1995. Their contribution is innovative and refreshing.

Hilaire — born in Palm Beach to Haitian parents — presents a labor-intensive work that addresses magical realism with elements of voodoo, giving importance to both the spiritual and artisanal aspects of her native country. Serpas builds sculptures from discarded objects, while Perez’s gaze is visceral and courageous.

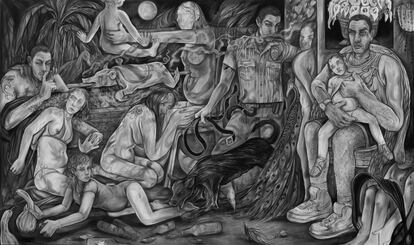

One of the works that can be admired in the exhibition is Family Romance, by Pérez. It’s an impactful mural made with charcoal, which denounces incest and captures the shock, horror, and pain of sexual abuse and rape perpetrated on children by their relatives. “So much of who we are is based on unlearning what we have absorbed,” the artist explains.

The inclusion of works by Venezuelan artist Magdalena Suarez Frimkess — who was born in Caracas in 1929 — is another inspiring part of the triennial. She discovered her love of art during her childhood, which was spent in an orphanage. Frimkess has remained in the shadows for much of her career: she held her first solo exhibition in 2013, when she was 83-years-old. At the Museo del Barrio, you can see several of her small ceramic sculptures based on cartoon characters — such as Popeye or Mickey Mouse — as well as some drawings.

“This triennial serves as a springboard for many Latinx people who are exhibiting their work in a museum for the first time, or [at least] for the first time in New York City. It helped boost the careers of the artists who participated in the first edition, such as Lucía Hierro, whose work was purchased by the Guggenheim after it was seen in the exhibition. Or Joey Terrill, whose work has been exhibited at MoMA and the Whitney Museum,” co-curator Susanna Temkin explains. “The triennial is accompanied by a catalog — which is extremely important — because while Latinx art is experiencing a boom period and many exhibitions are being organized, Latinx works aren’t usually documented, researched, analyzed, or integrated into the canon.”

The exhibition — which includes 10 commissions — is accompanied by two social practice projects. One is La misma canción (The Same Song) led by artist Mark Menjívar, of Salvadoran descent, who was born in Virginia in 1980. It’s based on a metaphorical comparison of the migratory patterns of birds with those of humans, as a way of using a softer image to frame difficult conversations about migration. In his workshops, he invites participants to create “welcome” or “farewell” signs, while also taking a birdwatching walk with him in Central Park.

The other project is led by Salvadoran artist José Campos through his Studio Lenca. The initiative was developed during workshops held in Mexico and New York: undocumented immigrants were invited to express their migratory experience in an artistic way, giving visibility to those who feel invisible.

“In a society that operates in constant tension with political validation systems, creating an art triennial implies opening a [front] in favor of flows and multiplicities,” explains Patrick Charpenel, director of the Museo del Barrio. “Possibilities are expanded and we open ourselves up to a new type of structural diversity.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.