Native American culture matters

After years of Black expression following the murder of George Floyd, Indigenous creativity has experienced an awakening across the United States, from art exhibitions in Washington, to series such as ‘Reservation Dogs’

The presentation begins with a reminder that the National Gallery of Art in Washington sits on the “ancestral lands” stolen from the Nacotchtank and Piscataway Indigenous peoples. It’s customary for certain official acts in North America to begin with these land recognitions… and it’s especially fitting when the museum in question is inaugurating The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans. This is the first exhibition that the institution has dedicated to contemporary Native American art in 70 years.

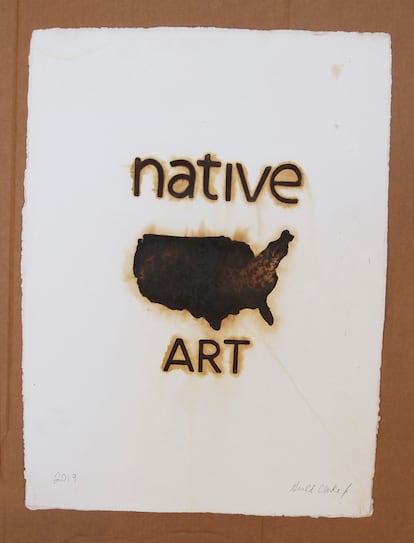

The exhibition’s curator is artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a member of the confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes of Montana. She has selected recent works made by 50 creators around the themes of Indigenous expression: land, identity, or landscape. There are sculptures, paintings, collages, live performances and videos; there are both abstract and explicitly political pieces. Some directly denounce genocide, while others play with irony and humor.

“I wanted to show that we’re a living people, with a future… not just something from the past,” Quick-to-See Smith, 83, explains to EL PAÍS. Back in 1991, she curated Our Land/Ourselves, another important exhibition with the land as a key theme. “The selection aims to transcend stereotypes of American Indian art, which has traditionally been understood only through artistic expression with materials such as ceramics, fabrics, or jewelry. These are the kinds of things you see in Indigenous art galleries in American museums.” She points out that the exhibition at the National Gallery is a rejection of the clichés that surround her communities. “We don’t go around half-naked with feather headdresses. We’re also not less intelligent than the white man. And we use more than just monosyllables.”

Thanks to the effort of bodies such as the National Gallery, 2023 has seen greater recognition of Indigenous culture in the United States, across the worlds of art, cinema, literature and television. Twice this past year, Quick-to-See Smith has broken what she herself describes as “the leather ceiling” — an image that, like the glass ceiling for women, helps her explain the invisible obstacles that separate Indigenous leaders from professional recognition.

In addition to curating the National Gallery’s exhibit, in the spring of 2023, Quick-to-See Smith became the first Native American artist to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. While it’s been devoted to American art for 93 years, apparently — until now — it didn’t consider Native American art to fall in that category. “All these milestones would have been unthinkable just two, three, or five years ago,” the artist sighs. “In the 1980s, when we were trying to make it on the New York scene, we did exhibitions in a gallery that they let us open in the American Indian Community House. They gave out food or bus tickets so that people could return to their reservations. And you know what? We never had an art critic from The New York Times or any specialized magazine show up.”

About 80% of the five million Native Americans in the United States live outside the reservations, which they were pushed into by the savage treaty colonialism that was based on violence, deception and broken promises

Those same establishment media outlets now celebrate the belated recognition of pioneers like her or G. Peter Jemison, of the Seneca nation, in upstate New York. After including him in an exhibition, MoMA has just acquired five of the emblematic drawings that he made in the 1980s on paper bags — a brilliant reflection on the experience of displacement in the big city. About 80% of the five million Native Americans in the United States live outside the reservations, which they were pushed into by the savage treaty colonialism that was based on violence, deception and broken promises.

The National Gallery has also purchased a painting of a sunflower by Jemison, to add to its small collection of native art. This process began in 2020, with the acquisition of Target (1992), a collage by Quick-to-See Smith that criticizes the trivialization of the tragedy of her people. “It’s fair to recognize that we’re very late. But this is only the beginning of the very necessary process of updating our collections,” promises Molly Donovan, curator of contemporary art at the institution.

The exhibition began to be put together the same year that George Flord was murdered by a white police officer. The killing of the African-American man unleashed a wave of anti-racist protests throughout the country in the midst of a pandemic. The Black Lives Matter movement gained strength. It was also a surprise test for American cultural institutions, which rushed to do their pending homework in terms of representation of minorities, making room for them in their programs, or hiring curators who hailed from different backgrounds.

Perhaps no sector has dedicated itself as much to this task as the art sector, always eager to identify (and make profitable) whatever is new, especially if it’s part of a social cause. This goes for both the market — as was seen at the recent Art Basel Miami Beach fair, in which the search for the next big native artist was a recurring topic of conversation among gallery owners and collectors — and for the institutions.

For the first time in history, the creator chosen to represent with a solo show the United States at the 2024 Venice Biennale will be Indigenous: Jeffrey Gibson. Gibson, a 51-year-old Choctaw-Cherokee artist, has just published An Indigenous Present, one of those books destined to mark an era. It offers an overview of contemporary art produced by some members of the 574 federally-recognized tribes. It’s also a refutation of some preconceptions about them. This Indigenous present — according to Harvard professor Philip DeLoria — “goes beyond survival and resistance. It speaks of a spirit of wit, irony, bravery, endurance, and faith in the future.”

“It’s easier for young people today to exhibit their work outside the traditional circuits of native art,” Gibson explained last week in an email. “Some come from families that have dedicated themselves to art, but above all, it’s important that a practice of Indigenous criticism and thought has emerged, better equipped to decipher [their work]. This didn’t exist when I started. There were loose opinions, but not a structured way of thinking about Indigenous elements in art.”

Native American culture also made it to the multiplex in 2023, thanks to Killers of the Flower Moon, a film in which Martin Scorsese recounts the violence suffered by the Osage of Oklahoma, when the whites decided to steal the oil they found on their lands. The director sought advice from the local community and cast Indigenous actors. The result has garnered praise among American Indian viewers for rescuing a tragedy unknown to the general public. However, there has been criticism about how the film focuses on characters played by Robert DeNiro and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Another audiovisual milestone has been the third season of Reservation Dogs. Created by Taika Waititi and Sterlin Harjo, it’s the first series with an entirely Indigenous writing room. Many of the actors are also Indigenous. With humor, it recounts the misadventures of a group of skeptical young people from the Muscogee Nation, who haven’t yet assimilated their own history. Using irony, it dismantles some of the stereotypes surrounding reservations, whose inhabitants enjoy limited sovereignty under the supervision of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. The episodes also cleverly play with one of the traditional clichés in the representation of natives in fiction: the idea of the Indigenous being in contact with the supernatural.

This was also the year that a Yale University professor — Ned Blackhawk, of the Te-Moak people of Nevada — won the National Book Award for nonfiction with The Rediscovery of America. The book reexamines five centuries of American history from the perspective of Indigenous struggle, survival, and resurgence. It takes a continental approach: the story doesn’t begin with the American Revolution of 1776, or even in 1619, when the first ships filled with enslaved people reached the coast of Virginia. Rather, Blackhawk starts the work in 1492, with the arrival of Columbus.

Blackhawk, who describes the experience of going to New York to pick up the award as “transformative,” belongs to a generation of academics who, as he explains in an interview with EL PAÍS, are watching “how the mythologies of American history begin to crumble.”

“Some talk about Indigenous power, but I attribute [this change] to the fact that the United States is gaining diversity and how we’re witnessing a racial and religious reconfiguration,” he adds. “Whites will become a minority at some point in the 21st century. And my book aspires to participate in that broader national conversation.”

The historian considers that this moment is “appropriate” for his culture. “At the next Oscars, we could see a native actress win (Lily Gladstone, for Scorsese’s film). There are TV series and novels that speak from our experience, while attention is being paid to native fashion and design. We even have one of our own in the president’s cabinet for the first time, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (of the Laguna Pueblo of New Mexico),” he notes.

Blackhawk points to two titles from the late 1960s that were pioneers in describing the Native American experience in the contemporary world: the essay Custer Died for Your Sins, by Vine Deloria Jr. of the Sioux people, and the novel House Made of Dawn, by N. Scott Momaday. Of Kiowa origin, Momaday won the Pulitzer Prize for the book in 1969.

The prestigious literary distinction eluded native writers from then all the way until 2021, when novelist Louise Erdrich of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians won it with The Night Watchman, a reconstruction of her grandfather’s political struggle for the recognition of Indigenous rights. That same year, Natalie Diaz (Mojave) won the Pulitzer in the Poetry category. And, the following year, Raven Chacón, a Diné artist and composer, also included in the National Gallery exhibition, made history by winning the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Erdrich — comfortably installed in the American canon — is one of the most respected fiction authors in the country, with her books translated into many languages. Among her followers, many have shown vitality in the genres of science fiction (Rebecca Roanhorse) or horror (Stephen Graham Jones). Tommy Orange, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma, stands out as well. His debut novel There There (2018) was praised for focusing on the “urban Indians,” with a story that takes place in Oakland. He has promised that a sequel will be published in 2024.

“We’ve been moving for a long time, but the earth moves with you, like memory,” writes Tommy Orange in his novel ‘There There’

The novel has a prologue in which Orange reflects on swapping the reservation for the city, “between buildings, beltways and cars,” and doing so by choice or by force (“as part of the Indian Resettlement Act”). “We’ve been moving for a long time,” he writes, “but the earth moves with you, like memory.”

Joy Harjo, of the Muscogee Nation, is the first Native American to be named poet laureate of the United States (she served from 2019 to 2022). She elaborates on this constant motion in the prologue to the anthology When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry. Published in 2020, it’s the most complete review of American Indian poetry to date: it includes 161 authors from 90 nations, with verses dated between 1678 and 2019. “We begin with the earth,” Harjo writes. “We begin with the land. We emerge from the earth of our mother and our bodies will be returned to earth. We are the land. We cannot own it, no matter any proclamation by paper state.”

“There is no singular story in these poems, just as the poets—the peoples—of Native Nations are not a singular people”, the Muscogee writer Jennifer Elise Foerster, contributing editor to the Anthology, clarified by email. “Native American poetry is a misnomer. What this collection is is a range of poems from poets of this country’s native nations. This is a collection that challenges country’s literary imagination to re-envision our stories of ourselves and our nations, peoples, and realities for the too many unacknowledged stories, songs and peoples that have been at the root of this Nation and that continue to flourish. It is key that more than 16 contributing editors and regional advisors, all native poets, were equal part in the ultimate curation of this book.”

They followed that geographical criterion to cover a landscape so vast that it discourages talking about Native Americans as being homogeneous: after all, some four thousand miles separate the Inuit people of northern Alaska from the Seminole people of southern Florida. “There are so many more poets we wanted to include in this anthology, and the most difficult part was having to adhere to the publication’s space and page limitations. So many essential voices we weren’t able to include, but that should demonstrate the astounding richness and depth of the poetics of Native people that have been largely unheard through several centuries of literature., Foerster says.

The concerns of the contemporary writers who made the cut — such as climate change, the destruction of nature, intergenerational trauma, or the failures of capitalism — largely coincide with those of the young artists selected for the National Gallery by Quick-to-See Smith. The exhibition’s catalogue argues that “much more than [land acknowledgments] are needed to appease Native Americans for what they have lost over the course of generations.” As a place to start, the artist tells EL PAÍS, “they can give us back the brains of our families.”

Quick-to-See Smith is referring to the fact that dozens of American institutions keep more than 100,000 remains of Native Americans, as well as sacred objects looted throughout the country. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act ordered their return. But more than 30 years later, many tribes are still waiting.

In Washington — the ancestral land of the Nacotchtank and Piscataway — the Smithsonian, an institution to which the national gallery does not belong, still preserves tens of thousands of these remains, in addition to a particularly macabre collection: 250 brains that an anthropologist named Ales Hrdlicka — a man obsessed with race — accumulated in the first half of the 20th century.

To watch, read and visit:

The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Native American Art. Exhibition. National Gallery of Art. Washington. Until January 15.

An Indigenous Present. Jeffrey Gibson. Art book. DelMonico Books, 2023.

Killers of the Flower Moon. Martin Scorsese, 2023. Movie.

Reservation Dogs. Taika Waititi and Sterling Harjo. Series. Disney + (three seasons).

The Rediscovery of America. Ned Blackhawk. Non-fiction book. Yale University Press, 2023.

The Night Watchman. Louise Erdrich. Novel. HarperCollins, 2020.

There There. Tommy Orange. Novel. Alfred A. Knopf, 2023.

My Heart is a Chainsaw. Stephen Graham Jones. Novel. Gallery/Saga Press, 2021.

Crazy Brave. Joy Harjo. Memoir. W. W. Norton & Company, 2012.

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry. Poetry anthology. W. W. Norton & Company, 2020.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.