US report shows horror of Indian boarding schools for indigenous children

An official investigation calculates that “thousands or tens of thousands” of students died at these federally-run institutions between 1819 and 1969

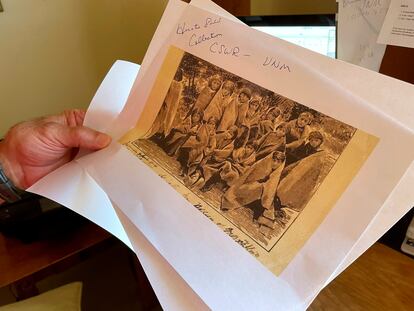

They were snatched from their parents’ arms, had their names changed and their hair cut, they were prohibited from speaking their own language or practicing their customs, and severe punishment was meted out for any act of disobedience. Many did not survive, their bodies buried next to the schools they were forced to attend.

The US government has published the first volume in an investigation into the demeaning treatment of Native American children at federally run Indian Boarding Schools over the course of a century and a half. So far, the inquiry has established that more than 500 children died in 19 of these schools. “That number is expected to grow” as the investigation progresses, says the report, which estimates that the count will climb into the “thousands or tens of thousands” as the horror of what happened in those schools is brought to light.

The investigation was launched after the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of indigenous children in Canadian boarding schools. A similar probe was launched in the US, and the first results were released on May 11 by the US Department of the Interior, which is responsible for the protection of federally owned lands and management of programs relating to indigenous communities.

The research shows that between 1819 and 1969, the federal system of boarding schools for American Indian children consisted of 408 federal schools in 37 states or what were then regarded as territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and seven in Hawaii. The investigation has identified marked and unmarked burial sites at 53 schools, and says that more are likely to emerge.

The report was presented by current Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American in office whose own grandparents were separated at age eight from their parents by the authorities. “The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies –including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as four years old – are heartbreaking and undeniable,” she said at a news conference.

Haaland believes that the results of this investigation should be used to give a voice to the victims and their descendants in a bid to heal the scars inflicted on the indigenous populations.

The 106-page report describes how the attempted cultural assimilation of Indian children was part of a broader goal to deprive American Indian tribes and Native Alaskans and Hawaiians of their land. “I believe this historical context is important to understanding the intent and scale of the federal Indian boarding school system, and why it persisted for 150 years,” wrote Bryan Newland, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, in the report’s cover letter.

The document goes on to compile historical testimonies that back this conclusion while highlighting the hundreds of treaties that were signed under duress in the second half of the 19th century that served to relieve the Native Americans of their territories. Some offered education in return, but the report notes that there is abundant evidence that many children were forcibly separated from their parents without family consent and, in fact, some parents paid with their lives for resisting.

One of the appendices includes maps showing the location of the boarding schools, with black dots covering the entire map of the US, though they are particularly dense in what is now Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona.

In many of the schools, the children were involved in livestock, agriculture and poultry farming, milking, fertilizing, tree felling, brick making, cooking and tailoring. This was considered part of their education, but the report indicates that they left school with little that could help them contribute to the country’s economy as adults. Under the guise of a supposed education, the students were, in effect, used as child labor.

The report documents how a policy of deliberate uprooting was carried out, with the federal government often collaborating with religious organizations and institutions to run the boarding schools. Not only were the children separated from their parents and relatives, but the schools made a point of mixing students from different tribes, meaning they would necessarily have to use English to communicate.

Commissioner of Indian Affairs William A. Jones pointed out in 1902 that there was a need for persistence regarding the initiative and compared Native Indian children to caged birds. He said that the first generation wants to fly from the cage because it retains its instincts, but after several generations the bird would rather live in the cage than fly out. The same is true of the Indian child, he added, according to the report. “The first wild redskin placed in the school chafes at the loss of freedom and longs to return to his wildwood home.” But, in time, these children develop “new rules of conduct, different aspirations, and greater desires to be in touch with the dominant race.”

The investigation has compiled a catalogue of ill treatment and abuse to which the children were subjected, beyond separation from their families and forced internment. “The federal Indian boarding school system deployed systematic militarization and identity-altering methodologies in an attempt to assimilate American Indian children,” the report says.

“Boarding school rules were often enforced through punishment, including corporal punishment such as solitary confinement; flogging; withholding food; whipping; slapping; and cuffing.” The report adds that older children were sometimes forced to punish younger children. Those who tried to escape from the schools were severely punished.

The investigation has already uncovered 53 burial sites on the grounds of these boarding schools and, in 19 of the centers, more than 500 child deaths have been identified. The report does not go into a direct analysis of the cause of death, but does note that the whole system of assimilation and uprooting was “traumatic and violent.”

Although the number of deaths are in the hundreds, the Interior Department anticipates that the ongoing investigation “will reveal that the approximate number of Indian children who died in federal Indian boarding schools is in the thousands or tens of thousands,” with many of them unidentified and buried in mass graves. “The deaths of Indian children while in the care of the federal government, or institutions supported by the federal government, led to the breakup of Indian families and the erosion of Indian tribes,” the report concludes.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.