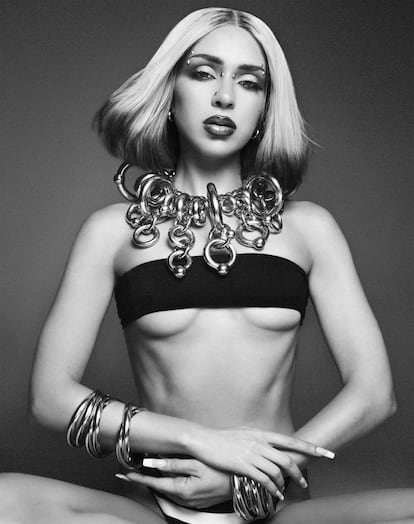

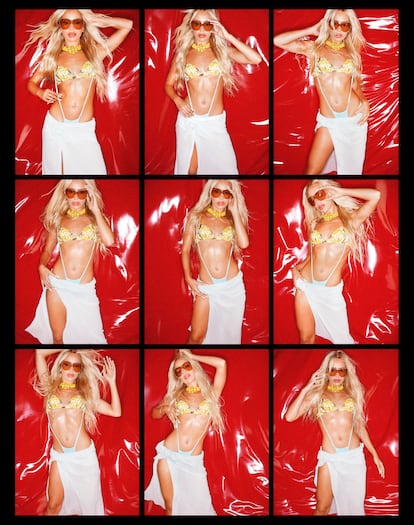

Bad Gyal, doing her own thing: ‘As a teenager, I felt judged because of how I dressed and expressed myself’

She’s the artist who wants to be both a radioactive Barbie and a neighborhood princess. With a style that blends Puerto Rican reggaeton and Jamaican dancehall, the Spanish singer has released her debut album — ‘La Joia’ — which is filled with Latin rhythms for summer nights

Bad Gyal burst onto social media in the spring of 2016 with Pai, a chaotic (yet sincere and euphoric) Catalan version of Rihanna and Drake’s Work. Today, we know that this was the first chapter in her rise to fame. Alba Farelo, 27, spent the last days of her adolescence sketching out her musical avatar. She did it in the solitude of her room, in a suburb of Metropolitan Barcelona.

This is how Bad Gyal was born: part-radioactive Barbie, part-neighborhood princess… and full blonde ambition. Her self-released singles defined her incubation period, while Alba Farelo Solé (her real name) worked as a baker or answered the phone in a call center. She was, slowly but surely, forging herself as a rebel.

Alba — a Pisces who believes in destiny almost as much as in perseverance and hard work — sensed that something substantial was about to happen in the Spanish urban music scene and in the Latin musical constellation. Jamaica dancehall and reggaeton were taking new evolutionary steps, beginning to make their way to the top of the food chain. Even an international superstar like Rihanna was bringing her attention to the “new” music of Puerto Rico. The planets were beginning to align.

Despite everything, in an exercise of common sense and pragmatism, Farelo kept Bad Gyal parked in a corner of her room. That is, until success became evident and, apparently, irreversible: “It took me a few months to bet everything on [my music],” she tells EL PAÍS, while being attended to by a makeup artist and getting dressed up as Bad Gyal. “I made an effort to complete my Fashion Design studies at the BAU (the College of Arts and Design of Barcelona), but it wasn’t for me.”

Among artists in the urban music scene, there’s a peculiar rite of passage that consists of letting their nails grow past the point where it’s almost impossible to work with their hands. This is a declaration of intent, like when bullfighters let their ponytails grow. It’s as if they’re saying: “I’m going to live from music. I won’t do anything else.”

Alba crossed that bridge about seven years ago. This year, she released her debut album — La Joia — and has racked up two mixtapes, a couple of EPs and a long string of singles. She’s gained success both domestically and internationally, with songs such as Fiebre and Pimp.

Her best songs brim with ecstatic forcefulness, aimed at the heart and the hips. She describes them as “underground hits,” assuring EL PAÍS that they were conceived “for people to sing them out loud on the dance floor.” They take over your body and your surroundings. Alba — through her alter ego, Bad Gyal — has the lifestyle of a toxic, arrogant and irreverent urban star… something that’s often misinterpreted and reviled. But her songs are carnal, intense, fierce. And — in the words of their creator — “authentic.”

Bad Gyal is a superhero costume, a seductive outfit that Alba Farelo wears when she wants to drink in the world in large gulps. However, she clarifies that her persona is “neither a shell nor a mask. Bad Gyal is me. With a cigarette in hand and a lost gaze in the mirror, she gives her thoughts on this dual identity that consumes a large part of her life and career. “[Bad Gyal] is a different and maybe a little better version of myself,” she shrugs. “[When] Alba’s heart is broken, Bad Gyal transforms that raw pain into an empowering song, an act of self-affirmation that she shares with the world, connecting with other broken hearts.”

“Alba, while still a child,” she continues — referring to herself in the third person — “went on tour with a disc jockey and her best friend. She landed in Paris, Bogotá, San Juan de Puerto Rico and Miami and was amazed by everything. She said to herself: ‘This can’t be happening to me, I’m a girl who made songs while locked up in her room.’ Then, Bad Gyal would get on stage to do everything possible so that the dream wouldn’t end.”

EL PAÍS accompanied Bad Gyal to a peripheral industrial warehouse, where she’s set to be photographed. She arrives at the agreed-upon time — she doesn’t keep anyone waiting just because she’s a celebrity. She’s accompanied by a small entourage: a hairdresser, a makeup artist, a legal representative and a stylist. She dresses unpretentiously, “in civilian clothes” (later, she will tell us that, from a very young age, she’s had an intuitive and visceral sense of fashion).

Alba greets everyone with a couple of kisses on the cheek and polite small talk. Then, she goes into a corner with her people. Half-an-hour later, Bad Gyal emerges: a stylized version of Alba Farelo, rampant and radiant, but equally loquacious and down-to-earth.

In an aside, between photos, Alba shares her oldest musical memories, which go back to the nights of her early childhood: “I remember, when I was about seven-years-old, listening to the legendary Estopa album (referring to an iconic Spanish rock/rumba duo, which peaked in 1991) with my parents and my siblings.” She also remembers, at a very young age, taking the lead when they did choirs in music class: “I don’t know if I had the best voice, but I was the most expressive and enthusiastic.” At that time, as she tells us, she dreamed of one day becoming the Beyoncé of her suburb.

“From the age of 13 or 14, I stopped dreaming on a large-scale. I assumed, in some way, that it was impossible to become a great international diva coming from a Barcelona suburb of 20,000 inhabitants.” She began to transform into the responsible, motivated and sensible rebel that — as she tells us — she continues to be. Her clothes and attitude became weapons with which to project the identity that she presented to the world.

“There was a stage in my adolescence when I felt judged for the way I dressed, expressed myself and behaved,” she recalls. “I had a very happy childhood, with my family and friends, in a quiet town where we could feel integrated and free, playing in the street. Nothing had prepared me for the rejection that I began to generate as soon as I got a little older. I was developing my fashion sense, posting photos on Instagram, expressing myself with whatever I could find within my reach. I was trying to find my people, my esthetic, my tribe. I was starting to get excited about the modern, the urban, the Caribbean… but I guess it must have seemed to many people in town that I was going around looking like a fucking painting and that I was becoming strange and dodgy.”

Bad Gyal was born, in a certain sense, from that rejection: “Jamaica and reggaeton weren’t hitting it yet. I went up and down [the street] with crazy clothes and three or four songs that I listened to all the time and that people didn’t understand. I took refuge in that. It was what made me different. I had bitter moments, in which I felt that my life hadn’t actually started, that I wasn’t finding the right direction. But I never doubted my project and my approach, because it was the shot of adrenaline that kept me afloat.”

On one occasion, Alba found herself involved in an absurd controversy when she described herself in an interview as “a posh girl with a lot of street smarts.” The daughter of the sought-after actor Eduard Farelo, Alba has a sister who is seven years young — Irma — who is also fighting for success in urban music under the stage name “Mushkaa.” Alba has been accused of belonging to a lineage of show business… of being a product, of lacking genuine “urban” credentials. She has, in short, established a narrative.

She settles the matter with an impatient pout: “Let’s say I’m a ‘townie’ posh girl. Not that I feel that way — far from it — but I accept the label. What I find interesting is that four urban fundamentalists accuse me of not having starved or dealt drugs, when I’ve never even tried to be marginal or dangerous, because that’s not my thing.”

In her opinion, authenticity consists of “not disguising yourself.” Or dressing up as an exalted, yet sincere version of yourself… the superheroine inside you. Like she does now. The substantial part of her story has to do with starting from very low and aiming very high. By being determined, ambitious, killing it onstage and never giving up.

Alba, in her own words, is a woman who sets challenges and overcomes obstacles. “I think I have talent,” she states casually, without false modesty. “I’m a performer, composer and producer. My songs are mine. They’re nourished by my life, my musical influences, my learning process and my experiences. I leave my soul in them and produce them by myself, or in the company of people with whom I have artistic harmony and whose career I respect and admire. Like Mag, the producer of one of my hits — Chulo — who’s worked with the best of the genre that I’m a part of, starting with Bad Bunny.

“I’m versatile and know how to play as a team. But I have a very defined identity and I always put something of my own on the table.”

She feels like she’s paid all her dues. She manages her social media accounts with little assistance and is exposed — on a daily basis — to the belligerent contempt of those who don’t understand her music. They condemn her attitude or gripe about her image. “Not everyone can like me,” she sighs “In general, I would say that my work and my life generate a very positive impact. There’s a whole community of people out there who are in tune with me, who’ve accompanied me in my career and have always offered me their love and I’m very indebted to them. What happens is that [the haters] are very loud.”

Social media has brought her many surprises, including a strange rumor that has proliferated in recent months: “Apparently, in a photo from one of my concerts, the shape of my [vagina] can be seen under my skirt. And someone has deduced from that image — I don’t really know why — that I was born a man. Some well-intentioned fans from the LGBTQ+ community have picked up this absurd and baseless story, maybe because fantasizing that I was born a man makes them feel a little closer to me. I’m sorry to disappoint them, because I was born a woman.”

“I don’t mind speculation about my gender. But it surprises me to what extent some fans try to direct the course of your career from social media, taking you in a direction that’s incompatible with your identity and your background, as if they know you better than you know yourself.”

In this new kind of fame, fans place a heavy emotional investment in their favorite artists, as if they’re the owners of their lives and careers. “I spend a lot of time in Miami and Puerto Rico, but when I return to Barcelona, I realize that it’s becoming more and more difficult for me to lead a normal life. [People] constantly recognize me and, more and more often, they insist not on just taking a photo with me, but on talking to me, explaining to me when they saw me sing for the first time and what I mean to them. I’m sorry, but I can’t spend five minutes with each person who approaches me. I appreciate the love, but I have to find a balance. I want to be accessible, but I don’t want having coffee on a terrace to become a little hell for the people I’m sitting with.”

There are some benefits to fame, of course. True success — as Alba conceives it — consists of “being heard, without a doubt, [and] in accumulating gold records… entering the top 50 most-played [songs] in the United States and verifying that what you do has an impact, that the work bears fruit.” And the rise to fame also translates into earning the respect of her colleagues. “One of the most intense experiences of my life has been recording my latest single, Perdió, with Ivy Queen, the legend of reggaeton, the absolute queen of Caribbean urban music. I’ve been listening to her since I was a little girl. She’s the queen of all this. She’s a Pisces, like me, so we’re both intense, sincere and energetic. From the beginning, a very special understanding was generated between us. I felt that she gave me her blessing… that she appreciated and approved of what I do.”

Bad Gyal has collaborated with top artists among the Latin musical constellation, including Karol G, Ozuna and Anitta. They all have the “cheekiness and cockiness that are the essence of the genre,” but, beyond the lyrics, “they’re warm, empathetic, very kind people, who don’t boast about anything.” Alba has found much more arrogant and ostentatious attitudes among “those influencers with half-a-million followers on Instagram who walk around Paris Fashion Week projecting aggressiveness and bad energy.” In dancehall and reggaeton — at least, in her experience — a relaxed camaraderie predominates.

Before saying goodbye to EL PAÍS, Alba spends a couple of minutes talking about her sister Irma and her single — SexeSexy — which they recorded together. When you listen to the song, it’s obvious how much their respective works fit together, like a pair of asymmetrical gloves made of the same cloth:

“No doubt,” Alba agrees. “The family [element] is there, the complicity between sisters. But notice that Mushkaa is very much her own person: she has very clear ideas and has never asked me for advice. Furthermore, we’re very different. She’s a lesbian and I’m heterosexual. She’s masculine, tough, a destroyer, while I’m more about taking care of myself, going to the gym and eating well. She’s much more intense, more aggressive, darker, more artistic. I’m a Barbie, a diva, a hitmaker. Our worlds are opposites, but it’s also true that they coexist very well.”

When asked if she’s a fan of her sister’s work, Alba replies emphatically: “Of course! If she would take at least one piece of advice from me, I would tell her to never doubt herself, no matter what.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.