40 years since the restoration of ‘Las Meninas’: A cleaning marked by controversy

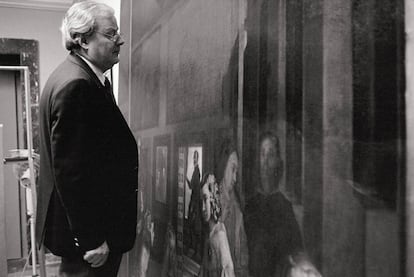

Enrique Quintana, a restorer at the Prado Museum, still recalls how John Brealy worked on one of the most iconic artworks in the history of Spanish painting, and how he was criticized for being British

In 1984, after a conversation between then-prime minister of Spain Felipe González and Javier Solana, who was the culture minister at the time, permission was granted to restore Diego Velázquez’s 1656 masterpiece Las Meninas. The person responsible for the project would be John Brealy, a British specialist — the fact that he was not Spanish was the subject of a great debate —, head of restoration at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

For almost three weeks, Brealy worked alone in a room at the Prado Museum in Madrid, where the painting is on display. He removed the layer of mastic varnish (resin) that had yellowed the work due to the passage of time. The frame was taken down and rested on shock absorbers. He used a ladder with wheels to reach the highest part of a painting that is over 125 inches tall. At that time, it was the best place to work because El Prado did not have the current restoration workshops.

The room in which Brealy worked was closed to the public, and only other paintings exhibited in that space kept him company. This room had two entrances, one of which led to the old offices of the museum management. The other one connected with the rest of the rooms.

Brealy had access to the room where Las Meninas was being restored, a place where only a few people had permission to enter, largely a young team of Prado restorers, among whom was Enrique Quintana, 26 years old at the time.

One day, screams began to be heard on the other side of one of the doors: it was a professor of Fine Arts with a group of students who demanded to see the painting and stop the restoration. They claimed that they had witnessed Brealy lifting layers of paint because, they said, they had seen color in the cotton swabs with which the restorer worked. The expert got scared, he thought they were coming to lynch him, he stopped his work for the day and left through the other door.

Another controversy was over Brealy’s nationality. Different people complained because, according to their criteria, only a Spaniard should have the right to touch one of the icons of Spanish painting. “I was condemned in advance. Before they knew what I was going to do, I had already been judged negatively. There was a sector of professionals who had established their initial position and, later, even if they were satisfied with my work, they did not want to give in,” said the expert in an interview in this newspaper.

Brealy did a general cleaning, that is to say, he did not divide the painting into areas, as some restorers do. He started on the right side, with the main point of light. This method marked the way in which many paintings in the Prado have been cleaned since then.

He didn’t touch anything else. The painting, which survived the fire of the Royal Alcázar of Madrid in 1734, was moved to Valencia during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and from there it was transferred to Geneva. It had barely sustained any damage, only some scratches. There was a cut on Isabel de Velasco’s skirt, another one on the right cheek of the Infanta Margarita. There was some damage on the back of the canvas, but it is truly a miracle how well it has been preserved.

Before completing the cleaning, Brealy called Manuela Mena, at that time deputy director of the Prado. He wanted her to be present for the final touch, which was administered on the last step of the door at the bottom of the painting, the place furthest from the viewer, with a very particular light that the expert recovered with the cleaning.

After cleaning the painting, Brealy gave it a final coat of natural resin varnish with greater stability to prevent yellowing. Before saying goodbye, he had a surprise for the Prado’s young team of restorers: he allowed Rocío Dávila and Quintana to give it the last layer, what is known as reintegration. “The day before I had been in a car accident, I broke a bone in my wrist and I couldn’t participate. So I was an observer and prepared the final report,” says Quintana.

Thanks to the restoration, visitors can once again appreciate the original depth and planes that Velázquez devised with his management of the light that enters, above all, through this window.

Plácido Arango (who later became a trustee of the Prado Museum) financed John Brealy’s stay in Madrid. That is, he paid his expenses, but not a salary, because the British expert did not charge anything for his work.

The restoration cost $5,400 at the time. The funds came from a donation of three million pesetas ($19,600) that Hilly Mendelssohn had made so that the Prado could invest in restorations. The Spanish state did not pay anything.

Credits:

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition