The monumental legacy of Richard Serra, sculptor of steel and time

The legend of American art, famous for his oversized yet minimalist metal works, embodied the idealized notion of the artist with a transcendental mission for whom both life and work are expressions of the same epic endeavor

When Richard Serra turned four, he was taken to the port of San Francisco, where he was amazed to see how large masses of steel were moved from one place to another. It was the beginning of one of the most fascinating careers in contemporary sculpture — a journey that came to an end on Tuesday, when the 85-year-old legend of American art died in his home on Long Island.

Serra will be remembered for his large steel constructions worked into graceful shapes despite weighing several tons each. Capable of creating sinuous interiors in which to get lost, his sculptures were revolutionary in that they invited viewers to admire them, but also, and above all, to walk through their cauldron-colored mazes. The best example of this style, a sophisticated and monumental reflection on emptiness, is located inside the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, where it has been on permanent display since 2005 in its most emblematic gallery, a titanium arm extending parallel to the Nervión estuary. The Matter of Time is made up of eight gigantic spheres, spirals and ellipses that marked the end of Serra’s journey towards the understanding of space. The installation ended up achieving the improbable feat of becoming an icon in its own right, capable of rivaling the Frank Gehry building that houses it, itself considered a masterpiece.

It was around that time that the famous Australian critic Robert Hughes, as fond of provocation as he was of slogans, defined him “not only the best sculptor alive, but the only great one at work anywhere in the early 21st century.” With his eternally frowning brow, his compact complexion and his laconic and reflective personality, Serra’s death further erodes a certain idealized notion of (male) artists as individuals permanently absorbed by a transcendental mission and for whom both their life and their work are expressions of the same epic endeavor.

The son of a candy factory foreman whose family came from the Spanish island of Mallorca, and a housewife who emigrated from Odessa, in present-day Ukraine, Richard Serra was born in 1939 in San Francisco. He used to brag about his working-class origins, because, he said, they gave him a strong work ethic. This attitude, far from being a pose, became evident very soon in his Verb List (1967-1968), perhaps his most famous text, which began with “to roll, to crease, to fold, to store, to bend, to shorten, to twist” and so on up to 100 “actions to relate to oneself, material, place, and process.”

As a young man, he shaped himself intellectually through English literature, which he discovered in college. He had formidable masters: the writers Christopher Isherwood and Aldous Huxley, the anthropologist Margaret Mead, the painter Philip Guston and the composer Morton Feldman. He read Emerson and the rest of the American Transcendentalists. He also immersed himself in the French existentialists, especially Albert Camus. He left the West Coast to study art at Yale, during which time he supported himself by working in a metal processing plant. In Paris, he deeply immersed himself in Brâncuși, an influence that was crucial in his own drift towards sculpture, while on the other side of the Pyrenees, in northern Spain, Eduardo Chillida and above all Jorge Oteiza were already embarking on similar reflections about space.

Goodbye to painting

His decision to quit painting was also an admission of defeat. When he saw Velázquez’s Las Meninas at the Prado Museum in Madrid for the first time, he surrendered to the evidence: “I thought there was no possibility of me getting close to that: the viewer in relation to space, the painter included in the painting, the masterliness with which he could go from an abstract passage to a figure or a dog. It pretty much stopped me. Cézanne hadn’t stopped me, De Kooning and Pollock hadn’t stopped me either, but Velázquez seemed like a bigger thing to deal with,” he declared in 2002 to The New Yorker.

He made a name for himself in New York by straddling the tribes of the minimalists and post-minimalists. He differed from the first by his taste for heavy materials. With the latter, in 1968 he shared the legendary exhibition at Leo Castelli’s gallery that earned him a name on the scene, thanks to his films and an installation in which he threw molten lead at the wall. After that early exploration of practices and materials, his love affair with steel would not take long to take hold.

His sculptures are spread throughout museums and cities around the world, from the Glenstone open-air park in Washington to Liverpool Street station in London. In some countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands, he is held in special admiration. But despite the fame that accompanied him for decades, that list ended up being mostly random. The city of New York, after eight years of controversy, ended up demolishing his piece Tilted Arc (1981), which had been installed in Lower Manhattan, and on one occasion the artist rescued two of his works from a park in Bilbao after learning that they were going to be auctioned off.

However, nothing surpassed the scandal of the disappearance, at some point between 1992 and 2005, of a work of his from a Madrid warehouse: Equal Parallel/Guernica-Bengasi (1986), property of the Reina Sofía, a museum that today exhibits in its permanent collection a version made in 2007. The disappearance was one of the most bizarre stories in the history of Spanish art in democratic times, and it inspired a book, Obra maestra (Masterpiece), by the writer Juan Tallón. Reminded about that episode, Serra used to respond with detachment that he believed that the thieves had surely “sold it to make razors.”

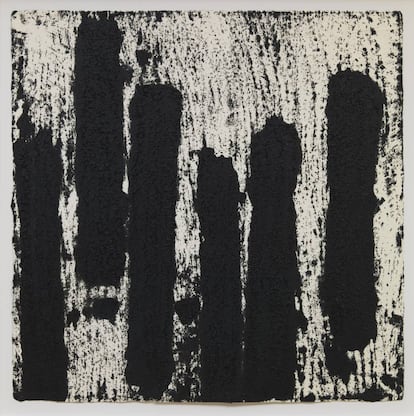

In recent times, health problems had caused him to dedicate himself to daily drawing, an art form in which he also left his original mark. For him, it was not a means (for the sketches of his sculptures he preferred to create 1:50 scale models), but an end. In an interview with EL PAÍS held at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, on the occasion of an exhibition of his drawings, he noted that he had been drawing as early as “five or six years old.” It was then that he realized what it meant to be a creator. “My mother would bring huge rolls of pinkish paper from the butcher shop that I would spread out on the sidewalk to draw on them. Wherever we went, she introduced me as her son the artist,” Serra said.

He had gone to Rotterdam with his wife, Clara Weyergraf, who survives him. Married in 1981, the couple divided their days between New York City, Long Island and Cape Breton, an enclave on the Atlantic coast of Canada that has served as a refuge for other key artists of the New York avant-garde such as Philip Glass or Joan Jonas, who was Serra’s partner in the 1970s. That day in Rotterdam, another port city, he had written down his ideas on paper, so as not to forget anything he wanted to say. “My drawings do not impose a discourse, nor do they pretend to be a representation,” he warned. “I don’t want them to serve as a metaphor, or evoke something pre-existing. Their task is to refute language knowing that this is impossible; we interpret everything through it. That is the ultimate function of abstraction: to refute superficial readings.”

A couple of weeks after that meeting, he did something that he reportedly often did: send an email to the journalist to clarify his arguments in the context of a discussion about the political usefulness of creation, during which he assured that “the best art is intrinsically useless.” “There are two positions an artist can take; commit politically or respond to their own internal needs,” he wrote then. “Both options were clearly represented by [Jean Paul] Sartre and [Theodor] Adorno. The first took the path of politics, Adorno opted for an individual articulation of his own aesthetics, divorced from ideology, in something that in his own way he understood as a form of political resistance. I have always leaned towards Adorno’s option.”

The origin of that discussion was criticism he received of his last great work, at least in ambition, a 2014 installation of four monoliths in the Qatari desert. Despite being a sought-after creator, he liked to show himself as an artist who is outside the management of the market. Business, he considered, had spoiled contemporary art, and particularly the New York scene. He blamed the generation following his own, the one led by Jeff Koons, which shamelessly embraced money in the 1980s.

During his last years, he tried to keep his cancer a secret, and asked journalists to cooperate. For those who knew him well, this attitude was yet another example of his obstinate personality — that of a young boy who watched large metal masses in motion at the port of San Francisco and ended up creating a universe of his own with the steel that formed his childhood landscape.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.