A vision reborn: Museum of iconic Spanish sculptor Eduardo Chillida opens once again

After closing due to management and financial problems, the magical outdoor sculpture park and gallery will welcome in visitors from April 17 to contemplate the work of one of Spain’s most internationally renowned 20th-century artists

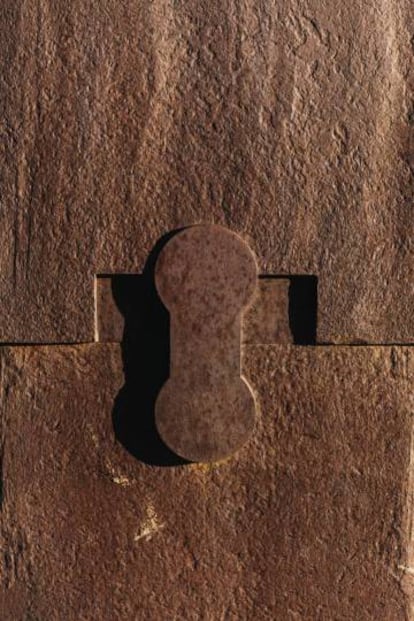

It’s 6pm and the fading orange light brings out a myriad of tones and colors in the corten steel structures standing in Chillida Leku, a unique outdoor museum dedicated to the work of Spanish sculptor Eduardo Chillida, located 15 minutes outside the Basque city of San Sebastián. The sculpture “Buscando la luz” (or, Searching For Light) is a perfect metaphor for the moment. The pink granite pieces, belonging to the series “Lo profundo es el aire” (or, How profound is the air), stand majestically on the estate. There is something ritual and ancestral about these works of art, they return us to an earlier world of dolmen tombs and monoliths, yet still capture the spirit of the modern age.

The deafening silence of the place is broken only by the noise of the excavators, tractors and trucks advancing across the ground. They are working against the clock. On April 17, the Chillida Leku museum will reopen, allowing visitors to see the most important work by Chillida, whose abstract iron and steel structures adorn cities and public spaces all over the world.

The drama that forced the museum to close on January 2011, a decade after it opened, is over. The vision of the late Basque sculptor, who died, aged 78, in 2002, and his wife Pilar Belzunce, who followed in 2015, had become lost in a perfect storm of politics, family concerns and lack of funding. But eight years on, Chillida Leku has been reborn, thanks to an agreement between the artist’s heirs and Swiss gallery owners Hauser & Wirth.

This magical museum in Hernani in Gipuzkoa province is the legacy of one of the most internationally renowned Spanish sculptors of the 20th century. Forty of Chillida’s mammoth sculptures fashioned out of iron, steel and granite stand among the oak, beech and poplar trees in 11 hectares of parkland, while 50 smaller pieces fill Zabalaga, a 16th-century Basque farmhouse, which is like a work of art itself.

The imminent inauguration of Chillida Leku – Leku meaning ‘place’ in Basque – will be marked by a retrospective of the artist’s work curated by his son Ignacio. Titled “Eduardo Chillida Ecos” (or, Eduardo Chillida Echoes), it will chart the sculptor’s creative course from the 1940s until 2000 with series such as “Gravitations,” a group of paper sculptures that highlight negative space, “Lurras,” sculptures made from chamotte clay, and huge iron works such as “Del plano oscuro” (or, Obscure Plane) (1956), borrowed from the Reina Sofia museum, “Hierros de temblor” (or Trembling Iron) (1957), “Yuque de sueños VII” (or Anvil of Dreams VII) (1959), and “Desosos” (or Wishful) (1954), owned by La Caixa Foundation.

Within the farmhouse, the upper galleries will feature a presentation of the artist’s work on show in public spaces around the world, paying special attention to Chillida’s iconic work “Peine del Viento” (or, Wind Comb), three sculptures that were bolted into rocks over the sea along the San Sebastián coastline in 1977. Perhaps the most popular project from the artist, these dramatic works were sculpted in collaboration with contemporary architect Luis Peña Ganchegui and have recently been granted protected status as a monument of cultural importance by the Basque regional government, the step prior to requesting UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

Meanwhile, Argentine Paris-based architect Luis Laplace has worked in close collaboration with local architect Jon Esery Chillida, the artist’s grandson, to update the existing installations while the prestigious Dutch landscape architect Piet Oudolft has made subtle changes to the design of the park and gardens. “We have tried to remodel a museum that was made in a different decade and to think about its needs today so there are changes, but they are barely perceptible,” says Laplace.

Two modern pavilions at the museum’s entrance will serve as a visitor’s center, a store and café and restaurant with chef Fede Pacha producing a menu from local seasonal produce. There will also be a small exhibition hall for Chillida’s works on paper.

Running the show is Mireia Massagué, formerly the director of the Gaudí Exhibition Center in Barcelona, though gallery owners Iwan Wirth and Manuela Hauser are behind the big artistic and financial decisions.

“The museum has always generated a lot of expectation,” says Massagué. “But the circumstances in which it is reopening are very favorable because Gipuzkoa and the Basque Country have changed a lot over the past 10 years. In the last five years, the economy has grown mainly around tourism, culture and gastronomy. This is a good moment.”

One of Mireia Massagué’s priorities is to get locals on side, something that was lacking when Chillida Leku first opened in 2001 – between 2000 and 2010 scarcely 15% of visitors came from Gipuzkoa. “Eduardo Chillida conceived this place as a museum on his home turf and it would not make sense without the involvement of local visitors,” says Massagué.

Meanwhile, Hauser & Wirth’s engagement in the project illustrates how private money and ambition can achieve what proved impossible in the hands of the regional authorities, indicating that we have entered a new era when public money is not the only option for large cultural projects.

According to one expert who prefers to remain anonymous, “Hauser and Wirth are going to accomplish what neither the family nor the authorities have managed and that is to put Chillida on the international map.”

Talking in the family home in a corner of the Zabalaga farmhouse, the artist’s sons Luis and Ignacio Chillida are clearly euphoric that the museum has been given a second chance. But they are keeping the funding details to themselves. “There’s no point in talking about money,” says Ignacio Chillida, who is currently compiling a catalogue of his father’s sculptures. “It’s an arrangement between two private parties, a gallery and a family business, so why go into it? If it involved public money, then of course we would have to, but as it is private, we don’t.”

Iwan Wirth and Manuela Hauser are not only involved in Chillida Leku, they are also the representatives of Chillida’s Estate on the international stage. Recognized by Art Review three years ago as the most influential pair in the art world, the Swiss duo hope to give the project a commercial push and boost Chillida’s prestige. Their presence in fairs and auctions all over the world, not to mention their galleries in Zurich, London, New York, Los Angeles and Somerset, will no doubt help achieve this goal.

“It wasn’t just a philanthropic decision,” says Iwan Wirth. “It was also strategic. The aim is to position Chillida Leku in an art world that has changed significantly since the museum was first established.”

Wirth believes that Chillida’s work has not yet received the recognition it deserves from the art establishment, something he is keen to rectify. “Chillida’s work is admired in Europe and Japan and it has the potential to be increasingly admired in the US and the rest of Asia. But compared with other major artists, we believe that he is underrated and our ambition is to change that in the future.”

Currently, this Swiss couple manage the rights of contemporary art stars such as Philip Guston, Ron Mueck and Paul McCarthy while also controlling the legacies of the big guns of the art world such as Henry Moore and Louise Bourgeois.

In fact, Wirth and Hauser had not even considered running the museum when they originally contacted the family. “They got in touch about becoming the international representatives of the Chillida Estate,” says Ignacio. “It was 2017 and we said yes, that might be of interest but the agreement would have to include the reopening of the museum and that they should manage the museum. And they said yes.”

Iwan Wirth, however, says they were aware of the need to reopen the museum from the start: “The fact that one of the artist’s main legacies was closed was not acceptable to us as the international representatives of the Estate.”

In any case, the Basque authorities appear relieved to get the matter off their hands. In fact, the current regional culture chief Bingen Zupiria says: “It’s wonderful news. We are talking about a strategic alliance between the family and one of the most important infrastructures in the art world. Hauser & Wirth is much more than a gallery. It is a conglomerate that deals in representing artists and has great potential to promote works, names and places. All this means that Eduardo Chilllida’s work will be repositioned in the art world.”

Luis Chillida, who ran the museum from 2000 to 2011, says that contrary to general belief, Chillida Leku never totally closed. “We continued to receive visitors who booked in advance,” he says. “There have been between 6,000 and 8,000 a year and they were able to visit in a very special way, but of course that was not what our parents wanted.”

In 2010, with an annual deficit of almost €400,000, Chillida Leku officially closed to the public. Despite the fact that 800,000 people had visited in the first 10 years, the sculptor’s heirs had to sell some of his pieces to try to plug the losses until finally, they were forced to let 23 staff members go.

“The famous Chillida Leku deficit really did exist and, unlike other museums that are given a budget to work on, we had to scrape by for a number of years,” says Luis. “And the only way we could do that was by selling works. We had no other way of generating money.”

The situation became critical in 2016 when San Sebastián was chosen as the European Capital of Cultural, yet its main cultural asset was closed.

The seed for Chillida Leku was sown back in 1982, the year in which the artist stopped working with Aimé Maeght, the gallery owner he had been associated with since the 1950s. Eduardo Chillida was looking for a permanent home for his work and there was hardly enough room for five or six of his sculptures in the family home in Alto Miracruz in San Sebastián. So he began scouting around for an alternative, a natural setting where he could keep his sculptures and have a bigger studio for his work with stone that was brought from the quarries of neighboring Usurbil as well as from India.

The dream started to take shape when Zabalaga’s former owner Santiago Churruca asked the artist for a lift to a house outside San Sebastián following an exhibition in Burdeos. When Chillida dropped Churraca off at Zabalaga, he took a look around and was immediately smitten. It was the perfect location for his creations.

During the 1990s, Chillida had a parallel vision that he developed from the popular granite series “Lo profundo es el aire.” The series is a study of the precise relationship between art, space and emptiness – a favorite topic of the philosopher Martin Heidegger. Chillida worked with Heidegger on the artist book Die Kunst und der Raum (or Art and Space) which was the start of the sculptor’s most beloved projects: “Tindaya.” The project involved hollowing a vast cube out of Mount Tindaya on the Canary Island of Fuenteventura but ran into objections from environmentalists who believed that, besides disturbing the local flora and fauna, it could cause the mountain to collapse.

While the Tindaya project had ground to a halt, the idea for a museum at Zabalaga had gathered momentum. In 1997, the renovations were finished and in 2000 an inauguration ceremony was attended by the leaders of the time – King Juan Carlos and Queen Sophia, Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar, the premier of the Basque regional government Juan José Ibarretxe and the German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

For the artist, returning to Hernani was like returning home. Like Ulysses, Chillida returned to his own Ithaca, to his father’s house, as it were, which he immortalized in 1987 with his famous sculpture of that name (“Nire aitaren etxea, La casa de mi padre,” inspired by a poem by Gabriel Aresti) near the Gernikako Arbola tree on the museum grounds.

It was in Hernani, after all, that he learned the art of iron work when he returned from Paris in 1951. Staying with an aunt in the Hernani neighborhood of La Florida, he spent his days forging iron at a local blacksmith’s, which would change the direction of his art from figurative to abstract. According to Hernani’s current mayor, Luis Intxauspe, “there are even people of a certain age who remember the artist when he worked at the workshop in La Florida. The reopening allows us to pass on his legacy to future generations.”

With a face that might have inspired a thousand sculptures, Chillida never chose the easy route. He believed the artist had a mission to tackle problems and his tireless efforts to establish Chillida Leku was testament to this for many years. If he had been able to witness its renaissance, he might have uttered the words he used as a title for one of his sculptures: Searching for light.

Tickets to Chillida Leku are now on sale online.

English version by Heather Galloway.