Frankenstein, the thousand faces of a creature that never goes out of style

Four film premieres, the filming of two new films directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal and Guillermo del Toro and various novels and comics open different perspectives for the myth created by Mary Shelley

“Mary Shelley was painfully young, a teenager in fact, when she published Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus, and she was able to transfer all her contradictions and questions to the monster and his tale, all her essential needs and her feelings of marginalization and inadequacy.” The reflection comes from Guillermo del Toro, from his book Cabinet of Curiosities. “I was overcome by the Miltonian sense of abandonment, the absolute terror of an absurd life. Tragedy did not depend on evil. That is the supreme pain of the novel: tragedy does not need a villain,” the tome reads.

The Mexican director not only knows what he is talking about, as an international expert in fantastic and horror literature and cinema—the so-called fantaterror—but at the age of eight he was already compulsively drawing Frankenstein’s creature from James Whale’s film version. Now, at long last, he is fulfilling his childhood dream: he is in Toronto filming his own vision of the myth for Netflix. He is not the only participant in this resurrection, which has experienced a boom in film and in comics in recent years. Some of these approaches change the sex of the creator or the creature to broaden perspectives and address new themes, such as bad mother syndrome or the impossible search for the perfect man.

After several years of vampires reigning supreme (that will continue; right now, a version of Nosferatu is being shot with stars), Frankenstein seems to be the trendy creature of the moment because of the ability to tell many things through it: Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Creatures discusses feminism; the Turkish series Creature (released on Netflix) takes on religion. Del Toro is shooting his Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac plays the doctor; Jacob Elordi, of Priscilla and Saltburn, stars as the creature); Penélope Cruz is part of the cast that is about to start filming Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Bride, which reimagines Whale’s second Frankenstein film —the one about finding a mate — and stars Christian Bale as the monster in 1930s Chicago, where the resurrected (Jessie Buckley) is a murdered young woman; a Sherlock Holmes vs. Frankenstein movie has already been completed; and last February saw the release of Lisa Frankenstein, directed by Zelda Williams (daughter of Robin Williams) and written by Diablo Cody. Last year, more indie titles drawing on Shelley’s work premiered: Laura Moss’s Birth/Rebirth, and Bomani J. Story’s The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster.

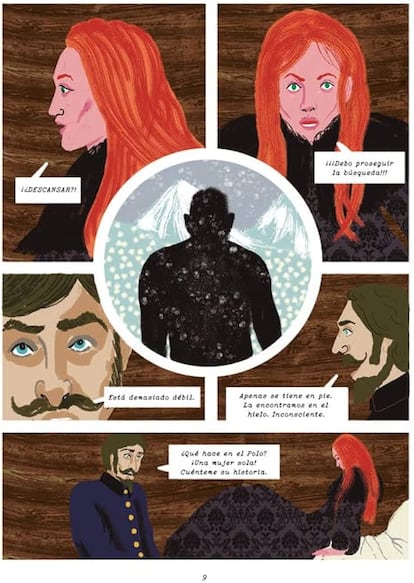

In her comic book Frankenstein (published last year by Bang Ediciones), Sandra Hernández turns Frankenstein into a young medical student fascinated by the universe’s secrets. After various experiments, she brings to life a composite of different parts of dissected corpses. The result is horrifying, the student flees the laboratory and, rejected by his creator and by humanity, hatred rots the creature. When promoting her work, Hernandez noted: “My version raises the issue of excessive ambition and how the fact of not bearing the consequences of our actions opens a kind of black hole in the soul. It also speaks to the rejection of the son by the mother, which transforms the victims into victimizers.” And she observed: “How is it possible that such a distorted and poor idea of this novel has reached us through films? I decided to change the protagonist’s sex because the metaphor of rejected motherhood was already served, and that is a question that adds even more horror to the story for what is supposedly unnatural and aberrant in something so human”— that is, bad mothers, which was already present in the novel Mary Shelley wrote at 18 years old.

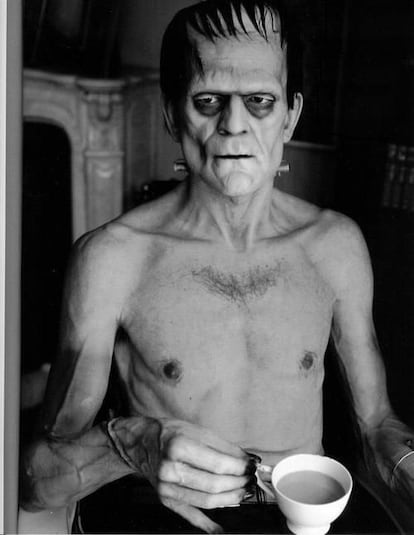

Whale, who created the first great Hollywood version in 1931, is responsible for the prevailing image of the creature, turned into a monster. After hiring Boris Karloff to play him, he sat at his worktable, as he described in interviews at the time: “I made drawings of his [Karloff’s] head, added sharp, bony ridges where I imagined the skull might have been joined.” From those pencil sketches, makeup artist Jack Pierce sculpted the stout forehead and the scars and screws that have been intimately linked to the character ever since.

The new approaches have moved away from that movie character, from a creature that in the novel speaks and philosophizes. Santiago Lucendo, professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the UCM and author of Frankenpolitics: Mary Shelley’s Monster as a Metaphor for Uncontrolled Power, explains: “In that text I spoke of Frankenstein as a symbol of emancipation. However, every time you delve into the book you find more readings. It is a well that never runs dry. The feminist element was already in the original, but on the 200th anniversary of the publication, in 2018, there were multiple approaches such as Jeanette Winterson’s Frankisstein: A Love Story [in which she even talks about transsexuality], and Elia Barceló's more youthful El efecto Frankenstein [The Frankenstein Effect].”

Lucendo is attracted to another part of the novel that didn’t make it into Whale’s version, “The creature’s learning and exploration. Hollywood took it out of that adaptation, as if it were taking the brains out of the novel. Instead, it is in Poor Creatures, both in the development of intelligence and its marvelous ingenuity. It’s just that he’s the first monster to speak, and all this time, in his [various] versions, he’s been silenced. I believe in empathizing with the creature, as Del Toro did in The Shape of Water.”

A Vibe

In the Los Angeles Times, Diablo Cody explains, “Having worked in this industry for 20 years, I do believe there is a collective creative consciousness because I’ve seen this happen so many times where suddenly a bunch of similar projects will surface. None of it was ever intentional, but there’s a vibe.” Her Lisa Frankenstein is structured as a 1980s horror comedy in which a lonely teenager, Lisa, encounters the reanimated corpse of a desirable 19th century beau, with whom Lisa had become obsessed in her hometown cemetery.

In Birth/Rebirth, an anti-social funeral home worker, obsessed with bringing the dead she receives back to life, steals the corpse of a young girl only to have the baby’s mother, a nurse, join her in raising the undead. And in The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster, the protagonist is a teenage girl who, frustrated by the violence in her community, resurrects her murdered brother. The director, Bomani J. Story, calls Shelley a “queen” in the Los Angeles Times, and explains that for his protagonist, whom her neighbors describe as a “mad scientist,” he drew inspiration from Shelley herself, his own sisters, and African American activists like Angela Davis and Tamika Mallory. In Poor Creatures, the creator (played by Willem Dafoe) is named Godwin, Shelley’s maiden name. That film’s screenwriter, Tony McNamara, said before the Oscars that the “Frankenstein element was the premise we knew we would preserve” from Alasdair Gray’s book on which the film is based, although both he and Lanthimos were careful to “not get caught in the weeds.”

All these directors are drawing on a legendary writer, Lucendo emphasizes: “Shelley was the product of both her father and her mother, and she is part of a generation of gothic novel authors who combine that landscape with intellectual depth. At the same time, Shelley is unique”; she even created her novel at a very special time, at the age of 18 at Villa Diodati in Switzerland, where she and her husband were visiting Lord Byron in the summer of 1816 — the year without a summer — although the work was not published until January 1, 1818. Later editions conservatively retouched it.

In film, television and theater adaptations have multiplied, some of which are especially brilliant, such as the one on the stage of the Royal National Theatre directed in 2011 by Danny Boyle, in which Benedict Cumberbatch and Johnny Lee Miller traded the roles of Victor Frankenstein and his monster every night, “a very interesting approach because it affects that double face,” Lucendo says. In the end, Shelley’s universe is not easily rendered. Those who approach it know it, and Del Toro himself will have to deal with his worst critic—himself—because at the time he wrote: “No adaptation—and there are some majestic ones—has managed to capture its full essence.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.