Christopher Nolan’s cinematic vision wins over Hollywood

The director of ‘Oppenheimer’, the most nominated film at this year’s Oscars, has built his career without conforming to the major studios’ mold

A well-known piece of film lore suggests that Akira Kurosawa was the first filmmaker to directly point his camera at the Sun. In his memoir Something Like an Autobiography, Kurosawa wrote that this was one of the taboos of cinematography when he was making Rashomon. He debunked the myth that it would damage the film, proving all the skeptics wrong. Kurosawa recognized the significance of featuring the Sun in one of the most acclaimed films that delves into the contrasts of the human experience.

Decades later, Christopher Nolan has also broken a taboo by using the atomic bomb to captivate global audiences, and is on the brink of clinching his first Oscar for Oppenheimer. The movie has amassed a staggering $1 billion (€915 million) at the box office while receiving widespread critical acclaim. This accolade could be a crowning achievement for the 53-year-old filmmaker, known for his unwavering cinematic vision in an industry where studios often impose their strictures on creators.

“Very few have earned that right,” said Tacita Dean, a British visual artist who works primarily in film. “If Chris wins the Oscar for that movie, he’ll inspire many young directors looking to shoot with old-school photochemical film. He’s been a pioneer in that area.” Dean, an activist defending celluloid over digital, has won awards for portraits of artists like Cy Twombly, Merce Cunningham and David Hockney, whom she introduced to Nolan. Dean thinks Oppenheimer will convince studios to release more 70mm films, which are 8.3 times bigger than 35mm, needing an IMAX projector and a 1.43:1 ratio (common widescreen is 1.85:1).

Nolan and Dean became friends in 2014, though they had crossed paths earlier — both studied at University College London. That’s where Nolan met his wife, Emma Thomas, with whom he has four children. Nolan and Dean are both active in promoting photochemical film, and participated together in Kodak-sponsored events in Los Angeles, Bombay and Mexico City over the last 10 years.

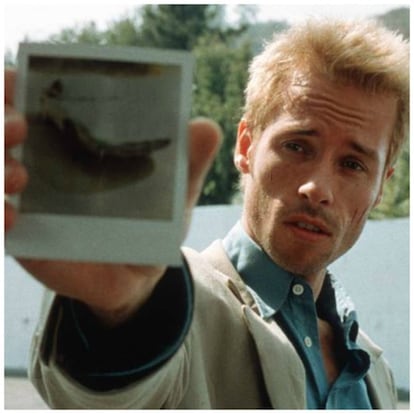

Something Dean once said stuck in Nolan’s head. “The camera sees time — it’s the first machine in history that can do this.” Nolan is a Jorge Luis Borges fan who has explored the passage of time through the lens throughout his career. In his second film, Memento, a man with amnesia (Guy Pearce) searches for his wife’s murderer. The film’s narrative is presented as two different sequences of scenes interspersed during the film: a series in black-and-white that is shown chronologically, and a series of color sequences shown in reverse chronological order.

The film was a success at Sundance, yet its unconventional structure challenged industry norms. Despite a year-long search for a distributor, it eventually premiered in just 11 theaters in its first week. However, Nolan quickly connected with his audience. Within three weeks, it expanded to 76 theaters, ultimately reaching 531 theaters and earning $25 million.

Memento earned Nolan his first Oscar nomination in 2002 for Best Screenplay, which he shared with his brother Jonathan, the author of the original short story. Subsequent nominations came for Inception in 2011 and Dunkirk in 2018, which garnered him his first Best Director nomination. Nolan’s wife Emma Thomas has produced all of his feature films, earning Best Picture nominations for Inception, Dunkirk and now Oppenheimer.

On March 10, Oppenheimer, the biopic about Robert Oppenheimer, the lead scientist of the Manhattan Project, is poised for 13 Oscars. It stands as a strong contender in a year where Barbie has also made a huge (pink) splash. Many of his fans view Nolan’s recent success at the British Academy Film Awards (BAFTAs) where he won two out of three nominations, as the breaking of a “curse” — five losses since 2011.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning adaptation of Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s 600-page biography shines at the Academy Awards amid a spate of CGI-heavy films with computer-generated stars. For visual effects, Nolan prefers to use small-scale models and optical printing, an old technique that uses one or more film projectors mechanically linked to a movie camera. It allows filmmakers to re-photograph one or more strips of film. In his book The Nolan Variations (2020), author Tom Shone quotes the post-production coordinator for The Dark Knight Rises, the last film in Nolan’s Batman trilogy. “He mentioned working on romantic comedies with more effects than that film, which only had 430 effects shots out of a total of 3,000.”

That’s also how they made the planets and space rockets in Interstellar. The science fiction movie prompted numerous comparisons between Nolan and Stanley Kubrick, a major influence on his work. “Your mind just takes in what you see, no overthinking, and that keeps you hooked on the story. That’s exactly what Chris is aiming for,” said Ian Hunt, who won a visual effects Oscar for the film starring Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway.

With Oppenheimer, Nolan aimed to replicate Kurosawa’s feat of capturing intense luminosity on film. But instead of the Sun, it was a nuclear bomb test in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Andrew Jackson, an Oscar-winning visual effects maestro known for Tenet, played a crucial role in realizing this vision. After a series of experiments, Jackson concocted a potent mixture of aluminum powder and iron oxide. When heated to around 2,000 degrees, this mixture produced gleaming pellets that burst into a dazzling light upon detonation. To enhance the visual impact, the footage was later edited in post-production to convey a heightened sense of explosive power.

An enigmatic director

The son of an English father who worked in advertising and an American mother who was a teacher and flight attendant, Nolan grew up between London and Chicago, and embodies the essence of both cultures. Nolan exudes politeness as he offers his actors concise guidance on set, maintaining a strict rhythm from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with just a brief lunch break. Gary Oldman recalls receiving one of the finest and most succinct pieces of direction while filming Batman. “‘Let’s do that one more time,’ Nolan told me. ‘There’s more at stake.’ Yep, got it... I know what you mean.” Enough said.

Nolan also embodies a strong sense of American determination. Recalling a peculiar encounter, Michael Caine shared how a stranger once appeared at his doorstep, eager to offer him the role of Bruce Wayne’s loyal butler. The seasoned star of Alfie politely requested to peruse the script in his own time. However, the persistent stranger — none other than Nolan — insisted, “Can you read it now?” And so, Nolan lingered in the room, sipping tea, until Caine completed his reading of Batman Begins.

During a recent interview with Stephen Colbert, Nolan revealed that he still waits patiently in the same room for actors to read scripts, which are printed in red ink on black paper to prevent photocopying. During filming, actors’ copies bear their names in large letters for easy tracking if misplaced. The technical crew are only given essential pages, rather than the entire script.

“Chris goes to many extremes to do things the way he wants,” said Tacita Dean. “All that is reflected in what ends up on the negative. Every little detail counts, and that attention to detail shines through in the end product.” We’ll soon see if Hollywood finally gives in to Christopher Nolan’s cinematic vision.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.