Castrated and forcibly feminized by Emperor Nero

In his book ‘Pax,’ Tom Holland reviews the period of splendor in Imperial Rome from Nero to Hadrian and tells of the terrible fate of Sporo, mutilated and forced to replace the deceased Empress Poppaea

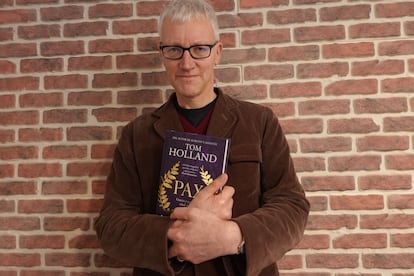

Tom Holland, the great chronicler of the history of Antiquity and especially of the ancient Romans, has returned. After a period of illness, he crossed a personal Rubicon with Pax (published July 2023), an exciting fresco about the era of splendor of Imperial Rome that lasted from Nero to Hadrian. And despite the book’s title, the period also included great military emperors such as Vespasian and Trajan.

In an interview in Barcelona in which he addresses topics as diverse as his passion for Herodotus (whose History he translated and for which he received critical acclaim) and his defense of hedgehogs, we talk about the Pax Romana, imposed by the legions with the sharp end of a gladius.

All in all, this monumental story takes us from the glittering marbles of the eternal city to the bloody barbarian forests of Germania and the violent sands of the Parthian Empire. It covers such sensational events as the Dacian Wars, the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried Pompeii, the Batavian Revolt, Titus’ destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, and the construction of the Colosseum. But nothing is as moving as the intimate stories of two young men who joined their destiny to the Caesars and died because of it.

One story, towards the end of the book, is about Antinous, the 12-year-old Greek boy from Bithynia with whom Hadrian fell in love and who later drowned under strange circumstances. During a cruise the emperor made along the Nile in 130 AD in which Antinous traveled as an official lover, the young man died — either murdered or sacrificed.

The other is a creepy and very sad case that Holland explains in the first chapter of his book. It concerns the young slave whom Nero castrated, dressed as a woman, and forcibly married because he reminded him of his dead wife (whom the emperor had kicked to death while she was possibly pregnant), the beautiful and promiscuous Empress Poppaea Sabina.

The sources (Suetonius, Tacitus, and Dio Cassius) have not recorded the true name of the unfortunate boy, who was tied to a table and had penis and testicles amputed by a surgeon (of the time). The name we have today is the nickname Sporus (seed or semen) given to the poor slave by the emperor. But Nero, immersed in the Frankensteinian fantasy that he was bringing his wife back to life (whom according to some he had kicked to death himself in a fit of fury), forced everyone to call the boy Poppaea and treat him as if he were the true empress. Thus, a new Poppaea, with the same soft skin and reddish-brown hair, combed and dressed like the late empress, occupied the emperor’s bed and was carried in a litter and honored as her.

With Pax, Tom Holland offers the third part of a Roman tour that began with Rubicon (about Julius Caesar), and Dynasty (about Augustus and the Claudian dynasty), and tells the fascinating story of Sporus-Poppaea, recalling his less well-known and no less tragic life after Nero’s suicide. He was passed from hand to hand, as a trophy and a valuable imperial attribute. After Nero’s death, the prefect of the Praetorians Nymphidius Sabinus treated the young man as a wife in order to shore up his position. “To sleep with Sporus, the wretched boy transformed into the image of the most beautiful empress in Rome, was to sleep with [the Empress] Poppaea Sabina,” explains Holland. The forcibly castrated young man, a living doll, symbolized imperial power and provided legitimacy to he who possessed him.

“The problem with writing narrative history is that the sources often focus only on the great figures,” reflects Holland. “It’s okay, because they are very interesting, but people like that young gelding who we would like to know more about are usually left out. They are fascinating stories that bring us closer to Roman society in a different way. It is a society that we cannot understand only through those who held power. We must hear about people from all walks of life: merchants, bureaucrats, slaves, and children.”

Holland reflects that although the whole story seems aberrant to us, we should not see the past, and look at Roman sexuality, with our modern eyes. It would be just as absurd (because it is anachronistic) to compare the experience of Sporus with present-day stories of transsexuality. For Sporus being turned into a woman was a humiliation. “The Romans fantasized about it a lot, but it was never seen as something positive.”

Holland closes his Pax (in which a thank-you goes to his oncological surgeon) with Antinous.

Is that symmetry deliberate? “Yes,” he admits.

“There are similarities between Nero and Hadrian, such as their love for Greece and architecture. And there are those two relationships with boys, although they are very different. Hadrian seems to have been truly in love with Antinous. But he also does something as surprising for the time like Nero had when he transformed Sporus into a woman. He turns his dead lover, who is neither a citizen nor a Roman, into a god and establishes a cult for him.

“Both Nero and Hadrian showed excessive emotions in their grief for Poppaea Sabina and Antinous, which to the average Roman seemed unmanly and was truly shocking. They are both transgressors. However, Hadrian looks to the future: a future in which the borders between the inhabitants of the empire disappear.” It could be said that Nero also had a vision (in his case materialized in a terrible, cruel, and monstrous way) of a world in which gender boundaries could be crossed.

It is not surprising that Holland, who began as a horror writer before launching into classical history and giving us books like Persian Fire, Rubicon, and Dynasty, was interested the history of Sporus.

How do you go from writing about vampires to writing about Antiquity and Caesars? “My original background is more literature than history, I started doing my PhD at Oxford on Lord Byron and, of course, he was Polidori’s model for his aristocratic vampire, so I started writing gothic vampire novels with that knowledge of Byron and they worked very well. But then I found the reality of the past much more interesting than fiction and anything I could invent.”

As we have said, there is a lot of war in Pax. “Indeed, but they, the Romans, saw no paradox in enforcing peace through wielding the sword. There could be no peace without war and without military supremacy (theirs, of course). Peace is imposed through violence.” In fact, the word emperor literally means victorious general. And Vespasian or Trajan are examples of that military, martial concept, of the imperial purple and of the empire.

A surprising element in Pax is that Holland shows sympathy for Domitian, the last of the Flavians. The late first-century emperor is considered one of the cruelest and his persecution of Christians is believed to be the worst.

“The truth is that he stabilized the empire’s finances and prepared Trajan’s conquests by increasing size of the army. He was frowned upon because he offended the senatorial elites. But only an autocrat could prevail. It should not be forgotten that he came to power amid a series of disasters that seemed to suggest that the gods were dissatisfied, and he wanted to appease them by returning Rome to its original values. He was very devout and believed in the mission of regenerating the empire. In essence, Domitian, more a censor than a tyrant, is close to some great 4th and 5th-century Christian emperors such as Justinian. But that did not prevent him from liking to personally shave his concubines, frolicking in the pool with street whores, and getting his niece pregnant.”

The historian, who is the younger brother of World War II specialist James Holland and is also responsible for writing documentaries, radio programs, and the successful podcast The Rest is History, is in favor of traveling to the scenes on which he works. And he remembers the impact he had on visiting the ruins of Sarmizegetusa Regia, the capital of the Dacians. “I took advantage of being invited to give a talk in Cluj and went there.”

Well, that’s in Transylvania, vampire territory.

“Yes,” laughs Holland, “Sarmizegetusa is a very sinister place and you can almost sense that the forests are full of strange creatures.”

In any case, there is no question of returning to the horror genre.

“I will continue writing about the history of Rome. I have four more books in my head. As I said, the story is more amazing and interesting [than fiction].”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.