The teacher, the student and a relationship that was a crime: the real-life case that inspired ‘May December’

Todd Haynes’ award-winning film runs every chance of netting Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman an Oscar, thanks to a story that Americans remember like it was yesterday: a couple that was forged in abuse

Gracie Atherton-Yu and Joe Yu are a happily-married couple who lead an anodyne existence, except for one thing: she was his teacher and they began their relationship when Joe was 13 years old. Two decades after the scandal, a movie brings their story to the big screen and the actress hired to bring Gracie to life went to the Yus’ home to prepare for the role. This is, in broad strokes, the plot of Todd Haynes’ May December, which was one of this winter’s most eagerly-awaited films.

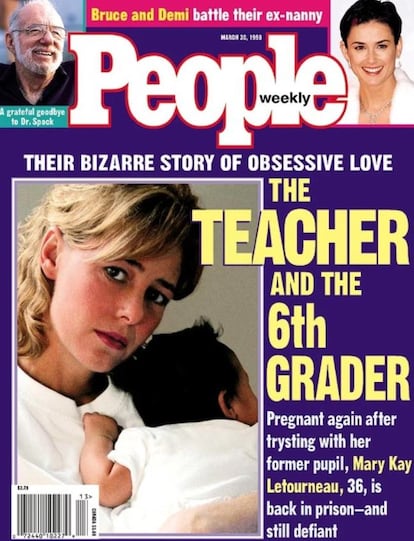

Its protagonists, Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman, were nominated for Golden Globes and will almost certainly be in the mix for the Oscars, but if right now their names share space in the tabloids with the recently-released Gypsy Rose Blanchard, it is not for cinematic reasons. But rather, because despite the script being listed as fiction, in the United States, everyone knows May December’s true protagonists: Vili Fualaau and Mary Kay Lauternau Fualaau; the latter, a romantic heroine for some, and for others, a dangerous sexual predator.

In high school, Mary Kay was just another student, an animated, cheerful, and studious blonde. Shortly after meeting Steve Letourneau, she became pregnant and they got married. They were not in love, but in Mary Kay’s ultra-conservative family, abortion was not an option. They had four children and not a lot of marital bliss. Steve was unfaithful, and she knew it. They also had financial problems: he worked handling luggage at the airport, and Mary Kay taught at Shorewood Elementary School in Burien, a Seattle suburb. She was a highly valued teacher in the eyes of her colleagues and a student favorite. She was especially fond of one of them, 12-year-old Vili Fualaau, a Samoan-born boy who could often be found hanging out at home with Mary Kay’s children.

One afternoon, Steven and May Kay had an intense argument in front of the kids, and Vili consoled her. According to the book If Loving You Is Wrong by Gregg Olsen, that was the first time anything happened between them. They both wanted it, according to Olsen, but Mary Kay had never put her feelings into words. The younger boy, on the other hand, had bet $20 with a cousin that he would sleep with the teacher. A police officer interrupted that moment of passion, and the two lied about why they were in a car together, and the boy’s age. The situation seemed strange to the officer, and he called the Fualaau’s family. His mother, Soona Fualaau, calmed him down. She trusted Letourneau. “If he’s with her, it’s OK,” she said, settling the matter.

A matter of genetics

There has been much speculation over how the boy’s systematic abuse could have gone unnoticed by Fualaau’s family. The answer is simple: his father was in jail (he was a felon who had 18 children with different women, and never helped care for any of them) and his mother worked two jobs to support the family, which took up all of her time. Besides, Soona trusted blindly in the selfless teacher. She had known Letourneau since she first taught her son in the second grade.

When Letourneau’s husband found letters from Vili, everything came crashing down. A cousin of Steve Letourneau alerted Child Protective Services to the true nature of their relationship. Not only were they having sex, but she was pregnant with his child. The police came to the high school, and Mary Kay wound up in court. The story hit the media and became America’s favorite scandal.

What they didn’t know at the time, but would soon find out, thanks to the relentless scrutiny of a sleaze-hungry media, was that a painful chapter of family history was repeating itself. Mary Kay was the daughter of a chemist who had rose to fame through her fight against the Equal Rights Amendment, and her fiery television appearances in defense of the traditional role of women and family values. She shared those interests with her husband, John Schmitz, a university professor, ultra-conservative politician and Holocaust denier who had moved his children to another school to prevent them from receiving sex education.

In 1982, he became famous against his will after it was discovered that he had two children out of wedlock from a relationship with one of his former students. When the story went public, Schmitz disowned his illegitimate children after the death of their mother. While the children wound up in an orphanage, Schmitz was buried with honors at Arlington Military Cemetery when he passed away in 2001.

A sentence and a baby

Mary Kay’s daughter was born as she awaited sentencing. She pled guilty on charges of sexual abuse of a minor and was initially sentenced to six-and-a-half years in prison, which was reduced to six months. In exchange, she was to have no contact with Fualaau, her five children or any other minor. But just two weeks after she got out of prison, they were once again found in her care by the police. A search of the car turned up $6,000 in cash, baby clothes and passports. “This case is not about a flawed system. It’s about an opportunity you foolishly squandered,” the judge excoriated Letourneau. This time there was no mercy: she received seven-and-a-half years in prison, the maximum sentence.

After beginning to serve her sentence, Letourneau discovered she was once again pregnant. The child was born in prison, and wound up being raised by Vili and his mother. The teacher spent most of her time in confinement being caught time and time again trying to get messages to Vili.

If those following the case as they would a daytime soap opera expected that Letourneau’s time in prison would dissolve the relationship, or that the transition to adulthood would change Fualaau’s feelings, they were wrong. When Letourneau got out of prison, she was 42 and he was 23. Fualaau fought to remove the restraining order against her and as soon as a judge overturned the ban on seeing each other, they were back together. What had been a crime of abuse became, for some, a love that could survive anything.

In 2004, Letourneau was interviewed on Larry King Live, wearing an engagement ring and saying how she was unaware she had committed a felony at the time. “I thought this could be trouble, but I didn’t believe that it was a felony. It just — I knew it just didn’t — just wasn’t normal.” She also told the host that their relationship had never been limited to the sexual. “It always has been a deep spiritual oneness.” Despite being a registered sex offender, Letourneau was not on the record as having had inappropriate contact with other minors. But that was not enough for many, who wondered what would have happened if Letourneau had been a 34-year-old man when the affair began.

The couple sold the exclusive of their wedding to Entertainment Tonight. Dozens of journalists were present, a helicopter hovered over the celebration, and it was reported that they received a half million dollars, which they have always denied. Letourneau’s brother walked her down the aisle. Her father died while she was in prison, and she had not been allowed to attend his funeral. Her teenage daughter served as maid of honor and her children with Fualaau as flower girls. Everyone was eager to hear the details of the newly legal relationship. We do normal things,” they told People. “We go out to dinner at our favorite Mexican restaurant and then we go to Blockbuster to rent a movie.”

The couple moved to Normandy Park, Letourneau’s former neighborhood. Her being a registered sex offender was no problem for their neighbors. “I think people are more concerned with the hoopla and the paparazzi being a pain and just disrupting their otherwise tranquil existence,” said the mayor at the time, Shawn McEvoy, to The Seattle Times. “Whatever your beliefs of their relationship, everyone respects everyone’s privacy around here. We want to give her the benefit of the fact she wants to move on with her life, get married and live a happy life.”

They were happy and tried to lead a normal life, but also to receive money linked to their extraordinary story. They weren’t the only ones. While Mary Kay was in prison, Vili’s family had sued the Highline School District and the city of Des Moines. The lawsuit filed by Soona Fualaau, Vili’s mother, claimed that both the city and school failed to protect her son from being victimized in an illegal and abusive relationship with Letourneau. Soona asked for more than $1 million in damages, but the suit was dismissed.

The couple co-authored an autobiographical book Un Seul Crime, L’amour (Only One Crime, Love) which due to licensing issues, was only ever published in France. Having become a celebrity couple, in 2000 their relationship was turned into a made-for-TV movie, All-American Girl: The Mary Kay Letourneau Story, in which Penelope Ann Miller plays the teacher. It received the second-highest ratings ever for the USA Network.

After regaining her freedom, Letourneau found a job as a paralegal and her husband worked as an occasional DJ. Not all of their business endeavors were in exquisite taste: in 2009, they organized a Hot for Teacher party at a Seattle bar. He deejayed and she hosted.

In 2019, they filed for divorce. An anonymous source told People that the couple had done everything they could to stay together. After separating, the bond between the two remained unbroken, they continued to spend a lot of time together, and in the company of their daughters. Mary Kay Letourneau died on July 6, 2020, victim of colorectal cancer. She was only 58 years old. Letourneau never regretted her decisions. Fualaau, for his part, has acknowledged that if he, as a grown man, felt attraction for a 13-year-old girl, he would seek help.

He is in a new relationship and in 2022, became a father for the third time. Georgia, his first daughter with Letourneau, is about to make him a grandfather. He tries to stay out of the spotlight, but he is aware that the controversial relationship that formed the best-known part of his life continues to command a dangerous fascination that will only increase with the release of May December. “I’m still alive and well,” says Fualaau, now 40 and still living in the Seattle area, where the scandal unfolded. “If they had reached out to me, we could have worked together on a masterpiece,” he told The Hollywood Reporter. Instead, they chose to do a rip-off of my original story. I’m offended by the entire project and the lack of respect given to me — who lived through a real story and is still living it.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.