How Boeing turned a 25-acre warehouse into a fake town in the middle of World War II

After the raid on Pearl Harbor, company employees focused on feigning that their assembly hall was a residential neighborhood to protect themselves from possible attacks. They achieved this using methods from the film industry: paintings, sets, and stage props

At the end of the 18th century, Empress Catherine II of Russia undertook a journey through the territories of Crimea and New Russia, which had just been annexed after the war against the Ottoman Empire. Technically, the purpose of the tour was to become familiar with the new conquered regions, but in reality, it was to impress Russia’s allies in the face of a probable new war against the Ottomans.

Since Catherine did not call herself ‘the Great’ lightly, being impressive had to be taken seriously. The problem is that Crimea, although geostrategically juicy, was not voluptuous enough for the empress’s tastes because it was quite unpopulated.

It was there that Grigory Potemkin, Catherine’s then-lover, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Army, and brand-new Governor of Crimea, appeared and decided that his beloved was not going to be embarrassed by seeing empty fields, so he put together a series of removable villages on the banks of the Dnipro River. These were wooden towns built with houses that were just façades and had nothing inside. Imagine big movie sets.

As the barge carrying the Empress and her entourage approached, Potemkin’s soldiers disguised themselves as peasants and occupied the town. Once the barge had moved away, the town was dismantled and the soldiers hurriedly transported it in pieces, to rebuild it downstream during the night. Of course, they set it up with a different configuration to pretend that it was another town and so that the Empress would not realize the cunning ruse.

In reality, the ruse was quite crude and, unless Catherine was as blind as a bat, the scheme would most likely not succeed. For this reason, modern historians seriously doubt the story. And yet, whether true or not, it served to name one of the most peculiar architectural and urban phenomena in the world. Since the 19th century, false towns have been called “Potemkin towns.”

Potemkin towns are a peculiarity, but the fact is that there have been — and there are — a good many examples across the globe. AstaZero, in Sweden, is a mock-up of New York’s Harlem, but it is only a means of studying car safety systems; Junction City IV looks like a Middle Eastern village, with its mosque and everything, if it weren’t for the fact that it is in the Mojave Desert and is used for maneuvers by the United States Army; or the North Korean Kijong-dong, whose only function is to impress South Korea’s neighbors who look at it from the other side of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

The common feature of these towns is that they play with the logic of reality because they are still models, but have been built on a natural scale. That is, they are models that try to resemble a model as little as possible, to the point that you have to get very close to realize that they are a set. For this reason, one of the funniest Potemkin towns was the one that Boeing built on the roof of one of its largest factories during World War II. Because, since no one was ever going to get close enough, they didn’t need to adhere to the 1:1 scale. They called it Boeing Wonderland.

In the mid-1930s, the former Boeing Plant 1 in Seattle began to sprawl. The company was growing at enormous speed, spurred by the expansion of international aviation and by an Air Force that was becoming increasingly important within the United States Army. Boeing didn’t just make commercial airplanes: some of the most powerful war machines in the skies had also come from their assembly lines. So in 1936, Boeing built a new, much larger plant. Enough to start manufacturing the B-17 Flying Fortress.

After the outbreak of war in Europe, and in view of a possible intervention by the United States, Boeing Plant 2 increased the manufacturing rate of the B-17, to which it added the new B-29 Superfortress which, with their longer range and superior weaponry, seemed destined to dominate the sky.

Things came and went in a climate of tense calm for a couple of years until on December 7, 1941, something happened that would change history forever (and the of the roof of Boeing Plant 2 for a time). The Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii, and the United States immediately declared war on Japan and officially entered World War II.

In reality, the U.S. Navy had already been operating in the North Atlantic theater for a few months, so entering the war was a given. However, what the United States did not count on was an attack on its own sovereign soil, which also fueled fear that the Japanese would reach the continental West Coast. Hawaii might well be in the middle of the Pacific, but it is also just a five-hour flight from San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle. And if Japanese aviation was able to reach California or Washington, it was capable of bombing the Lockheed facilities in Burbank and Boeing in Seattle, both of them capital strategic objectives in the future of the American participation in the war.

To try to avoid the catastrophe, the United States military used one of its most important assets: Hollywood. The idea was to camouflage the warehouses where the planes were manufactured and, in the specific case of Seattle, its gigantic Plant 2. Seen from the air and with a take-off runway next to it, the Boeing warehouse was a target that was too easy to identify, so, for a month in 1942, the frenetic efforts of the company’s employees were focused on pretending that their assembly hall was not an assembly hall but an innocent residential neighborhood. And what better way to do it than to use the systems, means, and methods of cinema, such as paintings, sets, and scenes.

In command of the entire operation was Colonel John F. Ohmer, who thought that, since he was using Hollywood gadgets, why not also use its professionals, so he hired John Stewart Detlie, production designer and art director of more than twenty films. Now, the dimensions of the undertaking he faced were much larger than those he had undertaken in those twenty-odd films. His latest set would measure 25 acres, which is the area that Boeing Plant 2 in Seattle occupied.

With the help of carpenters, stagehands, painters, and decorators, but also many Boeing employees, Detlie built a Potemkin town. An entire neighborhood of fake streets and sidewalks, simulated hills with hundreds of square meters of sackcloth, wooden trees painted green, cardboard fences, inflatable plastic cars and a bunch of houses that, in fact, were just plywood shells. It was all on the roof of Plant 2 because, after all, those on whom the deception would be played were only going to look down at the buildings from 10,000 feet in the air. At the time that was the bombing altitude of the heavy Mitsubishi Ki-21s of the Imperial Japanese Air Force. What’s more, as they were only going to be seen from above, the fake houses and trees only adhered to the scale in plan, but were noticeably smaller in elevation. Hardly anything exceeded 6 feet in height because no one is able to make such fine distinctions from 10,000 feet above.

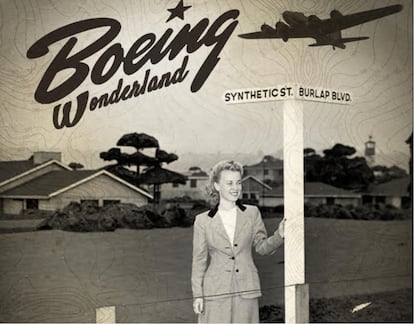

For the next three years, and until the end of the war, Plant 2 remained hidden under an idyllic suburb of Lilliputian houses. The plant workers were so proud of their roof that they even named the fake streets with signs that, obviously, only they were able to read. Of course, they were given names that referred to the particular condition of the neighborhood, such as Synthetic Street and Burlap Boulevard.

The war ended and the Japanese did not even approach the West Coast, so the monumental disguise of Plant 2 was never tested. Boeing Wonderland was dismantled in 1946 and, according to some chronicles, several of its remains, especially the trees and cardboard cars, were distributed among employees who had worked at the plant during the war. Maybe they wanted a souvenir from when they set up a Hollywood set to fool the bombers.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.