‘Gruesome, misogynistic, racist and nihilistic’: ‘Scarface,’ the film that took 40 years to become a classic

Four decades have passed since Brian de Palma’s classic was released, surrounded by controversy and bad reviews, before it became a cult object

Scarface premiered just over 40 years ago, in December 1983, and as hard to believe as it may be today, it arrived in American theaters — in the middle of the Christmas season — preceded by dire omens and a fierce discredit campaign that came close to undermining its commercial expectations. At one point, its distributor, Universal, saw it as a very high financial risk: it started with an initial budget of $12 million, but it ended up costing two or three times that — the versions differ, but in any case, a figure that seemed quite difficult to recover at the box office.

The film put the health of its protagonist, Al Pacino, at serious risk — starting with the integrity of his nasal passages, and it almost cost the lives of two specialists in action sequences. It sparked a conflict with the Florida Tourism Office and with the Cuban community in Miami that forced the production to move to Southern California. Robert De Niro did not want to star in it and John Travolta rejected the role of Manny, the right-hand-man of the main character, Tony Montana. Sidney Lumet resigned from directing it and predicted a flop of biblical proportions. It caused its producer, Martin Bregman, an anxiety attack, as well as a brief relapse into cocaine for its screenwriter, Oliver Stone. Brian De Palma attributed direct responsibility for the failure of his marriage to actress Nancy Allen to its tense and eventful production.

Furthermore, critics of the stature of Pauline Kael, Leonard Maltin and Jay Scott described it as a self-indulgent, failed spectacle. Intellectuals like Kurt Vonnegut and John Irving walked out of the theater on the day of its preview in New York, and the actresses Raquel Welch and Diane Lane, invited to the red carpet, were so stunned by the hyperbolic display of violence they had just witnessed that they were unable to utter a single word in its defense.

A delayed-action bomb

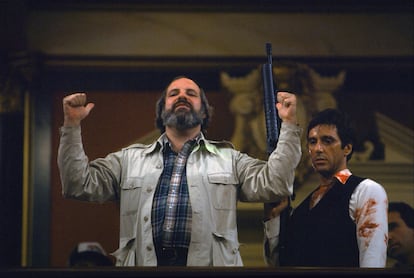

Today we remember it as a cult film, a cinematic legend on par with (or very close to) The Godfather, Taxi Driver or The Deer Hunter, but the truth is that Scarface was once a cursed project, on the verge of derailing on multiple occasions. The last one in the editing room, in November 1983, a few short weeks before its premiere. Brian De Palma had embarked on a feverish race against the clock to prevent the governing body of great American cinema, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), from giving it an X rating for its high dose of violence and its systematic use of obscene language. The director was already on his fourth version, and was especially reluctant to sink his scissors into the final scene, a climax of raw fury that was, to him, the core of the film.

Fed up with the creative interference of the censors, De Palma suggested a suicidal strategy to Bregman. “Let’s leave the film as it is; let them slap it with the X and then let’s file an appeal. Let’s make a scandal.” The theaters where it was going to premiere on December 9 had already announced it as an R-rated movie, and they threatened with removing it from their billboards if it ended up with the accursed X, which was reserved for pornography or B movies with extreme topics.

In the end, a middle ground was reached. De Palma presented a fifth version, almost identical to the fourth, to the MPAA appeals committee, and the conclave of 20 theater owners, studio executives and independent distributors bowed to the pressure from Universal and decided, by 17 votes to 3, to overturn the initial verdict and give Scarface the requested R. Shortly afterwards, Bregman declared that all that tension had cost him decades of youth. And, at the last minute, De Palma went ahead and released the fourth version instead of the fifth, convinced — rightly so — that the changes were so insignificant that no one was going to notice the difference anyway.

Detractors now and always

Prospect Magazine critic Rhik Samadder has a theory: that those who gave Scarface a hard time in 1983 were right. In his opinion, it is a mediocre film, in addition to being narratively incoherent and gruesome, misogynistic, racist and nihilistic from a political and philosophical point of view.

If in recent decades we have developed a selective blindness towards its unquestionable defects — he continues — it is because we have lost the ability to see it as it is and barely perceive its aura; impregnated, to boot, with nostalgia. It tells us about the last golden age of great American cinema, about Pacino in all his histrionic splendor, about Palma climbing to the top, about the rise of Oliver Stone as a great contemporary narrator and guru of the transition to an insolent postmodern sensibility.

Samadder adds that Tony Montana (a repulsive, mean, cruel and incestuous antihero, an unrepentant criminal without any redeeming quality) is a pop culture icon for boomers and members of the Y and Z generations, thanks, above all, to the uncritical appropriation of his figure by hip hop. The critic is fascinated by details such as the fact that, in the 2003 documentary Scarface: Origins of a Hip Hop Classic, P Diddy reveals “with bizarre precision” that he has watched the movie 63 times. For Samadder, Jay-Z, Notorious BIG, Nas, Kanye West and Raekwon are the genuine apostles of the secular cult of which Tony Montana is the object.

In Vulture, Jason Bailey goes over the controversy that surrounded the film, considered at the time little more than a xenophobic pamphlet that denigrated Cuban immigrants and echoed a toxic rumor: that among the close to 150,000 Cuban refugees from Port of Mariel that the United States welcomed in 1980, there were a high percentage of dangerous criminals, recently released from prison, that the Castro authorities had sent to destabilize the enemy. Bailey remembers how leaders of Miami’s Cuban community mobilized against the film, accusing it of perpetuating stereotypes and feeding the racist and nativist fantasies of the general public during a period of high volatility.

Oliver Stone replied with an obvious argument: “Tony Montana was a gangster. His mother and his sister represent the clean-cut Cuban community. His mother scolds him: ‘You’re a scumbag, get out of my house! You’re ruining your sister!’ So there is a strong morality in the movie. I knew about the criticisms even in advance, that Cubans were not like that. [...] If I’d done it about Colombians, they would’ve said the same thing: ‘You’re anti-Colombian.’”

Gangsters with Caribbean flavor

When Stone agreed to take on the script that Martin Bregman asked him to do in October 1982, the New York writer and future filmmaker was riding a wave. He had won an Oscar for the striking script of Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978) and had just written the script for Conan the Barbarian. If he was willing to get involved in the remake of a very distant classic, Scarface (1932), the chronicle of the transgressions of an Al Caponesque character directed by Howard Hawks, it is because Bregman proposed an exercise in lateral thinking that he found fascinating: instead of making another story of Italian-American gangsters, they were going to set it in the Florida of the Marielitos, the Cubans from the Puerto de Mariel exodus.

Stone spent several weeks in the Latin neighborhoods of Miami, meeting with police officers and criminals, and the atmosphere drove him back into the old habit of snorting cocaine constantly. From there he moved with his wife to Paris, where he wrote the script “in one sitting and completely sober.” By then, he already conceived the film as “a great Caribbean epic, exuberant, glamorous, erotic, full of energy, extravagance and color.”

When the man who was going to direct the film, Sidney Lumet, read the nearly 300 pages Stone had written, he resorted to the always useful argument of “creative differences” to dodge the bullet. Bregman tried to convince him, reminding him how well they had worked together in previous projects in which Pacino had also been involved, such as Serpico or Dog Day Afternoon, but it was no use. Lumet did not want to compromise his prestige by taking part in such nonsense, although he was gracious enough not to express his opinion in public.

Thus, Bregman turned to Brian De Palma, who was having trouble closing some financing deals after the box office failure of one of his most personal films, Blow Out (1981), and was willing, for once, to take on a commissioned film. At this point Robert De Niro had already rejected the role of Tony Montana. Glenn Close, Kim Basinger, Brooke Shields, Sharon Stone and a half-dozen other actresses had been considered for Elvira, the gangster’s lover, and Bregman had resigned himself to offering the role to an “icy and inexperienced” 24-year-old Michelle Pfeiffer.

Laxatives and thrones of blood

Filming was a 24-week marathon between November 1982 and May 1983 that began in Los Angeles to then continue in San Diego and Santa Barbara, with a brief and almost clandestine trip to Miami, where some scenes were shot in spite of the fact that the city that had refused to host the film, starting with one of the most famous: the brutal dismemberment of Ángel, Montana’s first partner.

In March, Pacino suffered severe burns on his left hand when he accidentally grabbed the barrel of a gun that had just been fired. While he recovered in the hospital, De Palma took the opportunity to shoot a series of action scenes that did not require his presence. In one of them, the premature explosion of a bomb caused serious injuries to two specialists. However, the most prominent incident, which a Variety article presented as a supreme example of the level of frivolity and delirium that Hollywood productions were reaching at the time, was the damage that Pacino’s nasal passages suffered after inhaling the high quantities of baby laxative and powdered milk that served as cocaine during the filming of the almost continuous narcotic scenes.

Stone contributed, perhaps unintentionally, to the film’s dark legend. As he told the specialized website Creative Screenwriting, he felt trapped on the set, annoyed by the exasperating slowness caused by the constant interruptions, the neurotic perfectionism of a Brian De Palma that was obsessed with countless trivial details and the puzzling insecurity of Pacino, who insisted on repeating takes over and over. When the final scene was being filmed, that orgy of violence that De Palma conceived as an homage to Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), Steven Spielberg paid a courtesy visit to the Santa Barbara set and insisted on lending a hand. De Palma commissioned him to direct the peculiar shot in which the killers first break into Tony Montana’s mansion.

In the end, the film survived various accidents and difficulties and arrived at the theaters on time. It had a notable performance in its first week, although it only grossed half as much as its great rival at the box office, Sudden Impact, the sequel to Dirty Harry directed by Clint Eastwood, another ultraviolent production reviled by the critics.

Scarface finished the season grossing a respectable but ultimately disappointing $45 million in the United States and $20 million worldwide. Profitability would come later, in a way that was unusual at the time: a quick release on VHS and Betamax in the summer of 1984 that made it the most rented film of the year, and the first to exceed 100,000 copies sold in home video format. Critic Gary Arnold described it as a guilty pleasure: you wouldn’t go see it at the daytime screening of a Times Square movie theater, but you are willing to rent it on the sly and enjoy it by yourself in the privacy of your home.

Today, no one seems to have much problem with it. Hollywood Insider considers it one of the ten best gangster films in history, on Quora they place it among the great classics of all time and its role as a great countercultural reference is barely questioned anymore. In Star Tribune, Gary Thompson remembers that some of the Oscar contenders in 1983 were Yentl, The Big Chill and Silkwood, three featherweights, and that the winner, Terms of Endearment, was not much better. The highest-grossing films of the year were Return of the Jedi and Octopussy. To that batch of harmless, almost immediately obsolete movies, Thompson opposes one of the films of the early 1980s that have aged best, Scarface, with its chainsaw slaughter, its giant mounds of cocaine and Pacino’s lost gaze as he insults left and right with a bizarre Cuban accent. It is difficult, for anyone who has seen it, to disagree with such a verdict.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.