The tragic untold story of the ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ trans icon

The film classic starring Al Pacino, about a small-time criminal who robs a bank to pay for his lover’s sex change operation, left out the impact that prostitute Elizabeth Eden’s struggle had on the LGBTQ+ community

On October 1, 1987, the Los Angeles Times published an obituary that read: “Elizabeth Eden; Basis of Dog Day Afternoon.” Although Eden was much more than the real story behind one of the most popular films of the seventies, the title represents a posthumous victory for those who fought for decades for the world to see the woman in her. Eden died at the age of 41 in a hospital in the city of Rochester, New York, where she fled to start a new life away from John Wojtowicz. Her charismatic longtime partner turned bank robber was immortalized by Al Pacino on the big screen. It was Wojtowicz who revealed to the press that Eden had not died due to cancer and pneumonia, as she wanted to be known, but as a result of AIDS-related pneumonia. More than 25 years after her death, there are several voices that try to vindicate what is, with her lights and shadows, one of the most important figures of the trans movement in the United States and which the Dog Day Afternoon failed to portray in its maximum splendor. “Her political impact runs far deeper than a botched bank robbery,” Tribune magazine says.

There is hardly any information about Elizabeth Debbie Eden’s childhood beyond the fact that she was born into a Jewish family in Queens (New York) and given the name Ernest Aron. She became one of the best-known young women on the New York scene in the early seventies due to her height, her beauty, her talent for dancing, and her scandalous character. She used to play records at parties with a portable record player that she carried with her, and turned to prostitution to survive. The 1960s were a time when any non-normative sexual orientation was still persecuted and criminalized, and homophobic beatings by groups of straight people or the police were the order of the day. But something had begun to change in the Greenwich Village neighborhood following the Stonewall riots in 1969, which multiplied the community’s demonstrations and gave birth to the gay liberation movement. One of the members of the Gay Activists Alliance, a nonviolent militant political organization, went by the name of John Wojtowicz.

This Vietnam War veteran was quite a character. A few years earlier he had left his wife, Carmen Bifulco, and his two children, and had decided to embrace what he himself defined as “sexual perversion.” “I don’t smoke or drink, I don’t take drugs or gamble. I’m a little angel, but I have horns. And when you have horns you can only do one thing: fuck,” he says in the TCM documentary The Dog. It was in the army when he had his first homosexual experience and stopped defining himself as a “Republican, conservative and warmonger” to join LGBTQ+ activism as an excuse to satisfy his chronic promiscuity. He met Liz in the summer of 1971. “When I first saw him, I knew. He had to be mine,” said Wojtowicz, who died in 2006 from cancer and always referred to Eden in the masculine. Such was the passion of their romance that they ended up celebrating one of the first — unofficial — gay weddings in New York, and even the general press reported on the union between the soldier, adorned with his numerous war decorations, and Eden, who was wearing a very expensive white dress.

The joy did not last long. The woman longed to undergo a sex change operation, but she did not have the money or John’s support to do so. She fell into drugs and tried to end her life on several occasions. “A lot of people had had surgery by then, and Liz couldn’t stop talking about it and how wonderful it would be to be a woman. She was not happy. Once she showed me her wrists and she had scars,” says one of Eden’s close friends in The Dog. In August 1972, she attempted suicide again by taking an overdose of medication and ended up being admitted to a psychiatric center. The episode was the trigger that made Wojtowicz — a textbook egomaniac prone to ravings — plan a bank robbery to pay for the long-awaited surgery.

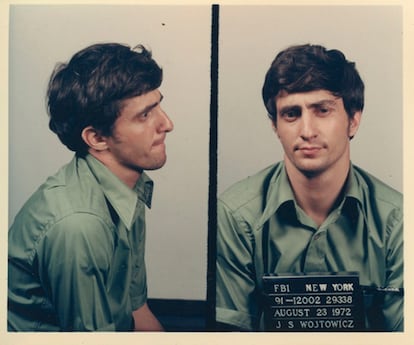

On the 22nd of that month, the ex-military man, accompanied by his accomplices Bobby Westenberg — who fled before the police even arrived — and Sal Naturile, entered the Chase Manhattan bank in Brooklyn. The robbery became a circus with thousands of curious onlookers who encouraged every act in this modern-day Robin Hood story and millions of spectators nationwide who were empathetic with the robbers for their altruistic and passionate cause. “It was a shock. Did you want gay liberation? Well, there you have it,” said journalist Randy Wicker. Both Liz Eden and Carmen Bifulco became media stars during the 14 hours that the robbery lasted and which ended with the death of Naturile — who was shot by an FBI agent — the release of all the hostages, and the arrest and subsequent criminal conviction of Wojtowicz.

The would-be robber did not receive any support from his Alliance colleagues, since the consensus among the members of the group is that Wojtowicz was mentally ill. But thanks to the premiere of Sidney Lumet’s celebrated film, his popularity skyrocketed to the point of being able to live on the profits from that failed robbery. He received hundreds of letters from fans, he signed autographs, he posed in front of the bank branch and in front of the tabloid press. He did whatever it took to squeeze every last dollar out of his feat.

Liz’s life changed too. With the money they received from Warner Bros for the rights to the story, Eden underwent her long-desired sex change operation. The film was a critical and public success. Her alter ego in fiction, the cis actor Chris Sarandon, was nominated for the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. Nevertheless, the fact that they rejected the trans actress Elizabeth Coffey Williams to play Eden “for being too attractive to play a trans woman” is an example of Hollywood’s historical transphobia.

As if it were the American sister of Spanish Cristina Ortiz, better known as La Veneno, Liz was also paraded like an exotic-festive object on television sets and the covers of erotic magazines showing off her new attributes. After the operation, she wanted to leave any relationship with John behind and start a new life. They ended up having bitter confrontations in front of the cameras, as she argued that the altruistic and already mythological endeavor thanks to Wojtowicz’s cinematic portrayal was not such. Eden claimed that the robbery was not intended to pay for her reassignment surgery, but rather to settle the debts he had with the mafia, and that, years later, John had become obsessed with her and threatened to kill her.

Liz Eden did not want to participate with John in what could have been a seminal story of the LGBTQ+ community in New York. These days, trans historians like Julian Gill-Peterson try to do her justice: “Liz may not have been a redeeming heroine in history, but she was not simply a passive bystander either.” Her close friends maintain that she was never happy, not even after her operation, and the press made her a broken toy after her short-lived fame. She moved to Rochester, on the Canadian border, and disappeared from the media spotlight for ten years while John tried to defend the romanticism behind his crime. They say that she returned to prostitution and that it was a transfusion of HIV-infected blood after a car accident that caused her to contract the virus. She died in 1987 and the Los Angeles Times published an obituary about her using female pronouns.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.