‘We cannot live here’: The families with trans children who are fleeing Republican strongholds

The harassing laws that prohibit gender-affirming treatment for youth are pushing many parents to move to places where their children can receive such care

This past summer, Debi Jackson — the mother of Avery, a 16-year-old trans teenager — decided that it was time to leave Missouri, a state that has just approved some of the most severe anti-trans legislation in the United States. After years of “full-time” activism in favor of LGBTQ rights — a time in which she became a public figure and an easy target — she launched a crowdfunding campaign in June to pay for her family’s relocation. 260 donors responded, contributing $15,553… money that the Jacksons used to leave their life in Kansas City behind.

There was a before and after on the day when a Republican legislator questioned Avery — who defines themself as “non-binary” — about their genitals. It was during a public hearing at the state capitol in Jefferson City. “We’d been standing up for trans people in Missouri for a long time… but that was pure violence, a really traumatic experience,” Debi Jackson says, via video conference from her new home. She agreed to do the interview on the condition of keeping her family’s location secret, “for security reasons.” There’s a website, she explains, dedicated to “tracking” her movements. The people operating it still haven’t managed to find her new home.

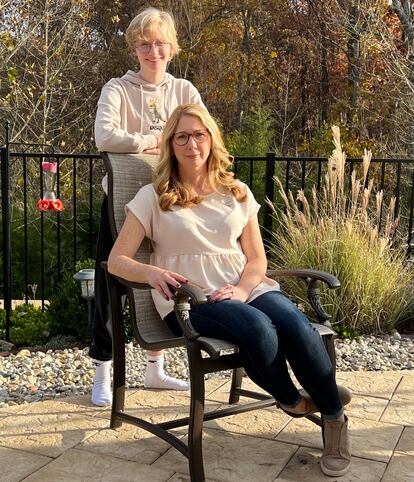

Others have chosen to remain in Missouri. Becky Hormuth, a teacher, is one of them. She lives in Wentzville — a town in southwest Missouri, about 45 miles from St. Louis — with her husband and their 16-year-old trans son, Levi. There, in a typical suburban house with a lawn, garage and basketball hoop, the family received EL PAÍS this past November, to tell a story that began about three years ago. It was during the pandemic when Levi told his parents: “I’m not who you think I am.” Doctors attributed the “elevated anxiety and depression” Levi was suffering from to be due to “gender dysphoria,” which they diagnosed. Starting testosterone treatment in December 2022 “changed everything.”

“It lifted his mood. He suddenly became more social, almost overconfident,” Hormuth recalled. In reality, the improvement had started earlier, “with a simple haircut.” That day, Levi explained, while sitting in the kitchen, he felt like “100 pounds were taken off of him.”

The recently-passed law SB49 prohibits Missouri minors from sex reassignment surgery, as well as “gender-affirming care,” unless those treatments — as in Levi’s case — had begun before the law went into effect in August. There are many treatments under that umbrella term, including psychological therapy, social transition (changing names, use of pronouns, clothing, etc.) hormones and puberty blockers. The majority of legislators wanted to veto this care for adults as well, but they had to settle for prohibiting it for prisoners and preventing the rest of Missouri residents from utilizing the state’s Medicaid for any such treatment. In addition, SB49 includes a clause that increases the period of time in which patients can sue doctors if they regret having undertaken gender-affirming care. The period has gone from two to 15 years — former patients can sue for malpractice upon turning 21.

Its Republican sponsors — who dominate both chambers of the state capitol — baptized the law with the acronym SAFE, Save Adolescents from Experiment. This summarizes the most widespread justification behind this type of legislation: that it’s being done for the good of children, since the bill’s sponsors and their supporters consider gender treatments to be harmful and experimental. They also argue that the youth (and their parents) lack the maturity to decide whether they want such treatments.

In practice, the extension of the deadline to file lawsuits has also complicated life for minors who have already begun their transition. Among the several clinics that have stopped serving them is Levi’s: the Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. The center has been the subject of an investigation by the state attorney general’s office, after an employee testified under oath that children were being persuaded into receiving medical treatment without being sufficiently informed about the side effects. The center conducted its own investigation, after which it concluded that the accusations were “unfounded.” Levi’s family — like those of a dozen other patients — also deny such allegations.

“It’s tragic that they closed it. We knew these professionals; we called them by their first names. We thought of them as part of the family, because, basically, they’ve saved our children’s lives,” Hormuth explained. She added that they still have “two treatments left” and that they’ve had to get “very creative” to “extend for as long as possible” the stock they were able to gather. They have testosterone, she estimates, for 32 weeks. And then? They always have the option of traveling every few months to Chicago — an admittedly expensive option — or at least crossing the Missouri River to anywhere in Illinois, where the laws are much more favorable. They’re also seriously thinking about moving. “We have met with a realtor and started making slight updates and repairs to sell our house. Not sure if we will move temporarily into the Saint Louis metro area, but Levi is not wanting to finish his senior year out in his current high school. We can’t live here.”

An hour’s drive from her home is — just across the state border — the Planned Parenthood health center in Fairview Heights, which offers this gender-affirming care. Colleen McNicholas — Planned Parenthood’s medical director for the St. Louis region (which includes both Missouri and Illinois-based populations) — explained this past week in a telephone conversation with EL PAÍS that, following the passage of the Missouri law, the clinic is prepared to “serve as many patients as possible, opening new spaces for appointments and expanding hours.” Basically, they followed “the script [taken from] what was learned after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade (1973)” last year, and with it, federal protection of abortion. Planned Parenthood — the largest reproductive health care network in the United States — built the Fairview Heights clinic in anticipation of the conservative turn that was coming in Missouri after the Supreme Court ruling. They estimate the year-over-year increase in patients seeking gender-affirming treatments to be at 41%.

The issue of abortion

After the interview at the Hormuth residence, a visit to the Fairview Heights clinic served to verify that the fight waged here by anti-abortion activists goes hand-in-hand with those who are attacking the rights of trans people. At the front door, two guys were handing out leaflets of both issues to those entering from the parking lot.

Perhaps because of her familiarity with these protestors, McNicholas also warns that — unlike other clinics — they plan to continue offering gender-affirming treatment to minors (who had already started the process) in the eight centers that Planned Parenthood has in Missouri, despite the threat of lawsuits. “We have experience working in challenging environments. We’re not so easily intimidated,” she emphasizes. At the moment, the staff hasn’t noticed the same “exodus of patients from other states” that followed the end of Roe. “But we don’t rule out that [cases may continue to increase] as the culture war intensifies,” she adds.

The “transgender ideology” has become one of the favorite arguments of the Republican Party. The right has pivoted towards this issue after its heavy hand against abortion took a toll on them in the polls. This was once again demonstrated on Thursday, November 30, during the debate between Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (Republican) and California Governor Gavin Newsom (Democrat) on Fox News. In the face-to-face argument, DeSantis resorted to rhetoric that often dominates the discussion on the conservative side of the aisle, denouncing the notion that California welcomes “children so that they can undergo [sex-change] surgery behind their parents’ backs.”

The dozen medical sources consulted for this article agree that surgery is rarely used in the cases of children and adolescents. “These politicians consciously play with misinformation,” explains Dr. Bhavik Kumar, a family doctor specializing in care for trans people. He works between Louisiana and Texas… two complicated places for someone in his field. “In almost all cases, adults undergo these operations. It’s a time-consuming and very expensive process, which you can only access, most of the time, if you live in a big city. In rural areas, it’s almost impossible [to obtain gender reassignment surgery]. Many people have to travel to other states, or abroad.”

Jameson O’Hanlon — a 55-year-old trans man who underwent an abortion in his youth, when he was a woman — defines himself as an “activist in favor of people’s freedom [to make decisions] about their body.” In an interview with EL PAÍS, he confirms that — based on his experience having undergone a sex-change surgery — that it’s an onerous procedure, which isn’t simply completed in one day. “I’ve been [undergoing] the process for seven years. In the case of the transition from woman to man, if your health insurance doesn’t cover it — and this is typically the case — the torso operation [alone] can cost between $8,000 and $12,000. The lower one is even more expensive.”

The country’s leading medical organizations — including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics — oppose banning gender-based care for minors, so long as it’s provided appropriately and with psychological supervision. Not administering it, experts affirm, can plunge adolescents into depression, or even lead them to suicide. According to a recent study by the Williams Institute, at the University of California in Los Angeles, 42% of American adult trans people have tried, at some point, to take their own life.

And Dr. Kumar defines “most” hormonal treatments and puberty blockers — approved 30 years ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to stop early development — as “reversible.” However, the debate is open: in some countries, such as the United Kingdom or Norway, public health agencies have stopped prescribing them this year due to doubts about their suitability to treat gender dysphoria.

However, despite the opinions of experts in the United States, anti-trans legislation is advancing. In one shocking graphic, a map of the country from January 2021 is compared with the situation in the U.S. this past fall. In the map on the left, the 50 States appear in white. In the one on the right, 22 states — the ones that have since approved laws that prohibit minors from accessing gender-affirming treatments — appear in color.

This is a demonstration of how, in just three years, the politicians who rule the parts of the country where 42% of the American population lives have turned trans rights — with the help of the conservative media — into an obsession. Putting an end to trans rights has become a legislative priority. 1.3 million adults and 300,000 minors in the United States define themselves as transgender, according to another study by the Williams Institute, which estimates that the second figure has doubled in the last five years. In a country with 330 million inhabitants, these individuals make up a miniscule percentage… especially when compared to the amount of space in the public debate that has been taken up by this subject.

According to the ACLU, over the past year, state legislatures across the country have approved 84 regulations that curtail LGBTQ rights. These bills are divided into four large groups: those that prohibit medical treatments or social transition for minors; those that prevent choosing a bathroom based on gender identity; those that require sports to be played according to one’s biological gender and those in the educational field. The education-related measures, for example, prohibit the teaching of sexual orientation in schools, veto books that deal with the subject in the curricula, or force teachers to inform parents if a child has changed their name or pronouns in class. Some states have also passed bans that affect adults or young people up to the age of 26.

A recent survey put the percentage of trans people who have moved to other places in the face of this legislative changes at 8%. Extrapolating the numbers, this would up add to about 100,000 people. Meanwhile, 43% of trans Americans confessed that they were contemplating the possibility of doing so.

Contested laws

Some of these rules have been challenged in the courts. This is the case in Florida, where far-right Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill this year that outlawed gender-affirming treatments for children and adolescents. The legislation has also threatened health professionals with prison sentences, while reducing options for trans adults, by establishing that medicines related to these treatments may only be prescribed after the in-person signing of a consent form and only by doctors (and not by nurse practitioners, which was previously permitted). The part of the legislation related to minors is the part that has been appealed.

This past May, EL PAÍS visited one of the Planned Parenthood centers in Miami (which has never treated minors). It was observed how these judicial ups and downs affect the lives of professionals, who never know exactly whether what they’re doing is legal. At the time, patients were also concerned, flooding one of the nurse’s email accounts with questions such as “Should I start thinking about moving?”

“This is all part of a coordinated attack with electoral calculations,” affirms Cathryn Oakley. She’s state legislative director of the Human Rights Campaign, an organization that defends the civil rights of LGBTQ people. “These are the same groups we’ve fought against for decades. The same ones who — once the debate on equal marriage (sanctioned by the Supreme Court in 2015) was over — looked for something different to instill fear in their voters. They found transgender people [to be a good target]. At first, they became obsessed with the bathrooms… and it didn’t work out as well as they expected. So, they went for the children; at first, in sports, and then, in healthcare. They need that wedge as part of their culture war. They’re not concerned about the damage they may do to these people, who are among the most vulnerable groups. What matters to them is making people afraid, so that they vote for politicians who will ‘save’ them from that threat.”

“They want to control the lives of others and — in the process — cover up the fact that, deep down, they’re not doing anything about the things that really matter for the education of young people. My child’s decision about their body cannot harm anyone. How can they say it’s wrong for [Avery] to look for a way to feel better?” asks Debi Jackson, the woman who left Kansas City behind. During her conversation with EL PAÍS, she acknowledges that the Missouri case hasn’t attracted as many national headlines as those in Florida, due to the presidential aspirations of its governor, or Montana, where Republicans withdrew Zooey Zephyr — the first trans legislator in the state’s history — from speaking for three days, after she accused her rivals of “having blood on their hands” over a law that curtailed the rights of transgender people. “But Missouri is the heart of America, a testing ground for what can happen elsewhere,” Jackson argues.

She explains that she comes from “a conservative background,” but had to rethink “a lot of things” when Avery told her at four-years-old that they didn’t feel like a boy. Then, in 2014, Debi starred in a video on the matter that went viral, when — “luckily” — virality was in its infancy. In 2017, Avery was on the cover of National Geographic magazine, with the headline Gender Revolution. Those were different times.

“I think the violent reaction came when [people] realized that we weren’t going to keep quiet. Trans people were allowed to exist while remaining silent… they’re not supposed to be proud of themselves. But it would be a horrible way to go through life: hiding, or not being able to express who you really are.” Debi Jackson is used to being told horrible things about the way she raises Avery. However, the escalation of the attacks in the last “two or three years” ended up breaking her.

Speaking up has also taken a toll on Becky Hormuth. At the end of the conversation with EL PAÍS at her home in Wentzville, she explained that some of the families who she organizes with have decided to stop appearing in the press, due to the consequences that this entails. Many parents feel that they’ve obtained limited results when it comes to influencing the mood of Republican politicians.

Before saying goodbye on the porch, she reviewed some of the places — from New York to Seattle — where several other families have moved, so that their children can continue treatment. The list of those who are leaving hasn’t stopped growing.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.