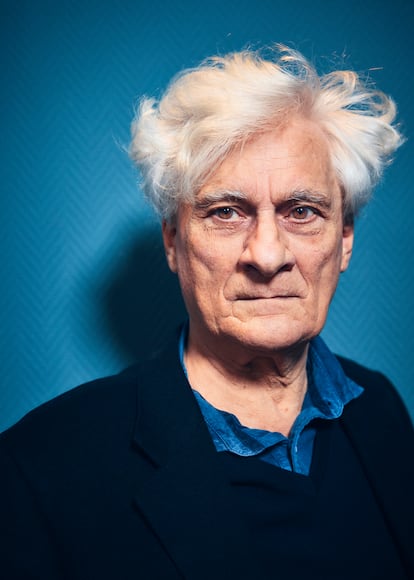

Franco Berardi, philosopher: ‘We have to abandon the reproduction of the species’

The Italian thinker and activist, a reference for the libertarian left, discusses his essays on contemporary slave labor and the tyranny of work with EL PAÍS. He believes that humanity is going through mass psychosis and urges us to imagine ‘a cure’ for our disease… if it has a cure, that is

Franco Berardi has been distraught all morning. Hamas’ attack against Israel has been followed by the indiscriminate war waged by the Israeli army against Palestinians in Gaza. The excesses overwhelm the Italian philosopher. Standing in the lobby of his Madrid hotel before beginning his interview with EL PAÍS, he thinks over what is happening, looking for the words to conceptualize it. His white hair is abundant, free as the wind. He says: “Only one word makes sense: ‘dementia.’” He also notes that geopolitics has died — that what’s happening now is something else entirely: “geopsychosis.”

Berardi, 74, is a reference point of the 1970s-1980s leftist autonomous movement, a grouping of minor political significance but considerable artistic-intellectual weight. Bifo — his nickname since he was a child — thought about politics in classically political terms for decades. But as he gets on in age, he’s begun to think about politics in psychological terms, as if the world is no longer merely an unbalanced and unfair system of power relations. More than ever, he feels that the Earth is an emotional and seriously ill nervous system.

He’s visiting Madrid to present a revised edition of his book of essays — Contro il lavoro (in English, Against Work) — which are centered on his criticism of labor within the capitalist model and the possibility of emancipation from work. “The continuous struggle of the exploited to subtract [free time] from work — to gain spaces of autonomy — is the foundation of liberation,” he wrote in 1977, in an article titled The Revolution is Fair, Necessary, Possible. In another paper from 2017 — The Precarious Imaginary — his theoretical evolution is evident, both ideologically and poetically. “I don’t believe that politics has the power to consciously act on our future. I think we have to understand our present as a condition of spasms, of painful accelerations that cannot be improved by will, but only by sensitivity.”

Berardi takes a seat on the right side of this journalist. He explains that he has hearing problems from attending so many concerts in New York in the 1980s. It was the time of the New Wave: he earned a few bucks writing reviews for an Italian music magazine. He had left his country to distance himself from two dangers in his environment: heroin and the Red Brigades. “They were both too close to me.”

Question. What relationship did your mother and father have with work?

Answer. My father, Giuseppe, was a schoolteacher. Catholic and communist. He liked his job very much. My mother, Dora, was also a schoolteacher, but she had three children and had to leave her job to take care of the house. I think that left her with a trace of bitterness forever.

Q. As a child, did you like school?

A. Yes, on top of that, I was the teacher’s favorite student. He was a very nice man. He was a blind professor and a Marxist, essentially anarchist, I would say. I was a child who loved to read. My first philosophical reading was Schopenhauer, when I was 12. At school, with my friends, I started talking about the idea of suicide, of the freedom to die. One day, the father of one of the children showed up at school with great indignation: he told the teacher that it was forbidden for his son to associate with the child who spoke about free death.

Q. Natalia Ginzburg says that the writer Ivan Bunin (the first Russian awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature) once told Anton Chekhov that he didn’t feel like writing and that he wrote very little. Chekhov replied: “That’s wrong. The essential thing, as you know, is to work all your life without ceasing.” What do you think?

A. I agree with Chekhov, although we first have to understand that the word “work” has a double meaning: it means both free activity and forced activity — or wage labor — which implies submission. I hate any type of activity that requires me to work eight, 10 or 12 hours a day to earn my bread. And, at the same time, I really like what I do every day and no one imposes it on me. I’m a great worker.

Q. How has your criticism of labor evolved since your texts from the 1970s?

A. At first, the object of my analysis — what I rejected — was the working-class model of the assembly line. I discovered very quickly that I hated this, when I was only 16. I lived next to a second-grade glass factory where only women worked, about 400 young women, mainly from southern Italy. It was hard and harmful work; they were exposed to cancer from cobalt. They made syringes, thermometers... I had already gotten close to the Communist Party and I went there every day to chat with the women. They took a liking to me. They didn’t have a union and, after two years, I helped them organize a strike that lasted three weeks. The boss — a guy called Romagnoli, I remember him well — had to accept what they asked for. They weren’t much older than me, but they saw me as a crazy kid who went around handing out propaganda leaflets and telling them that they had to oppose work. But, in the end, we won the fight. For me, it was a fundamental political experience of worker autonomy.

In the 1980s, a profound change in [the economic] model — which was linked to the formation of the electronic network — began. I [studied] it from the beginning. It seemed that everything could change in a positive direction, that robotics could free us from manual work and that this new network would boost free shared activity. I made a mistake. At the turn of the century came the dotcom crash, there was a radical shift in the social form of the internet. The dream of free [connectivity] was broken — everything was verticalized with the emergence of large [tech] companies. The possibility of the internet as a free place is over, meaning that we’ve entered this essentially sad place, this depressive space of virtual relationships. We’re disembodied, forced to work for an invisible boss.

Q. What has happened over the last two decades?

A. They are two different stages. In the first, there’s still an ambivalent awareness of the process: the culture of the critical and participatory network remains, with that artistic, philosophical, militant spirit that is at the root of the [movements that followed the 2008-2009 financial crash], such as Occupy Wall Street, or the [anti-austerity protests in Spain] 15-M. At the same time, a transition is being made away from that framework of self-criticism, toward what has happened in the last decade: the complete alienation in our relationship with the internet, the absolute subjugation to the factory of virtual production. The symbol [that marked the start] of this era was the explosion of Facebook. The defeat of social movements and the establishment of social media happened at the same time.

Q. And what has been happening in the 2020s?

A. In 2001, I wrote The Factory of Unhappiness. I said that we had to be careful with the internet’s ability to create loneliness, but I still didn’t pay as much attention to the psychological dimension. In the second decade [of the 2000s], this seemed more important to me. Today, I think more psychologically than politically. The factory of unhappiness has become a psychopathological concentration camp. Social and geopolitical relations can only be explained through psychotic categories. The categories of politics have become empty and are analytically useless. As happened a century ago, we’re experiencing another mass psychosis. I don’t know if this is curable, but I consider the last task of my life to work on thinking about how to produce cures for mass psychosis, an extremely difficult task.

Q. What do you propose?

A. To begin with, we must be aware that politics — left and right — means nothing. With the small exception perhaps being Spain, where the left seems to continue to exist. But if I look at what has happened with [Alexis] Tsipras’ Greece or in the United States, where Biden is worse than Trump...

Q. Biden is worse than Trump?

A. Absolutely. His anti-immigration measures are harsher and his foreign policy is more criminal. Let’s be clear: Trump is the most horrible of horrors, but [the two men are] two sides of the same madness. Trump didn’t even have a foreign policy. For him, Putin was a friend. He’s a fascist murderer, but any white man is a friend, because Trump’s geopolitical idea is simply reduced to the fact that his enemies are not white people, but rather everyone else. [His conception is] the final fight between the race of predators and the others, the non-whites. But is this totally appalling and racist idea worse than the madness of the war in Ukraine? Biden — or, rather, Biden’s circle — has carefully prepared [the terrain] to sever Europe’s economic and energy relations with Russia, especially Germany’s deep dependence on [Russian energy]. They sent the Ukrainians to be massacred by Putin and the Russians to be massacred by Zelenskiy. But returning to what we were talking about: since the time of Tony Blair, we cannot speak of the left and the right as different strategies.

Q. So what do you propose?

A. If we can understand that the destruction of civilization is not the manifestation of a political strategy, but is instead the expression of a mass psychosis, we can begin to work politically in another way. Politics becomes psychotherapy. This doesn’t mean putting psychologists in schools. It means much more: we have to stop all forms of production of mass loneliness and destruction of the bonds of solidarity. We have to stop the culture of competition. Ultimately, we have to abandon war and politics. We have to abandon precarious and enslaving labor. This is already happening, with the Great Resignation in the United States, or the shift in Italy: thousands of people used to compete for a hundred positions, but now, there are vacancies. Finally, the most important matter is to not create future victims of the foreseeable climatic and atomic infernos. We have to abandon the reproduction of the species.

Q. At this point in time, what should we do with the central ideas of civilization and progress?

A. The word “progress” no longer means more than the accumulation of capital and economic growth, which isn’t a viable model. Although, it may have been useful or necessary at a certain time in history. I’m not sure that industry was inevitable in the history of humanity, but it happened. It happened and that’s it. But now, it’s evident that economic growth means more destruction, more suffering, more ecological catastrophe, more poverty. We can no longer consider the idea of “progress” to be a positive one.

Q. And what about civilization?

A. I use the expression “social civilization” as the possibility of everyone’s participation in well-being and economic production. In that sense, civilization has been a positive development. But one cannot reflect on this term without also conceiving of civilization as the project of power and submission of others by Western whites. This white civilization is in crisis… or, more than in crisis, in true disintegration.

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine and now with the war on Gaza, we’re seeing that, on one side, there are the Americans — not all the Americans, the old white Americans, and not all the Europeans, only the old white Europeans — and the Israelis. On the other side is the rest of humanity. We have a confrontation between an old white minority that retains all the global economic-military power and a majority with no other point in common than the will for revenge. Since Mao Zedong, China wants revenge… the West will pay dearly for the humiliation [that it subjected China to] after the Opium Wars. We’re going to witness the revenge of the non-whites. We’re already seeing it.

Q. You’ve written that Israel has no future.

A. Israel is dead. I won’t make it to the end of the decade, but you will, you’re young. You can tell me about it.

Q. But you’re only 74 years old!

A. Yes, but I prefer to leave soon: 80 seems like an intolerable number to me. I don’t want it, no. But hey, you’ll get to 2030 and you’ll tell me if Israel still exists. I really don’t believe it, because this project has suffered a very profound deterioration, in the first place because of that nefarious individual who is Netanyahu. He won’t survive the disaster he has caused and — at the same time — he represents an overly powerful set of forces that will prevent any left-wing alternative from prospering, something that practically doesn’t exist in Israel.

Q. Your generation idealized youth. In a way, your generation invented it. Do you think this makes it more difficult for people such as yourself to accept old age?

A. Old age is, naturally, a personal problem, for your body, for your mind. But today, it’s also a structural problem, it’s the biggest problem of white civilization. I’m very interested in the topic of old age: it’s exciting from a philosophical point of view, from a literary point of view... Do you know Arthur Schnitzler? He’s an Austrian from Freud’s time, who wrote very interesting things about becoming old. Also Sara Mesa: for me, Dough Face is one of the most profound books of our time! The young woman and the crazy old man who meet and talk about birds, about everything and nothing at the same time...

What I believe, in short, is that we don’t know how to live old age. We don’t know how to process the idea of becoming old, which is becoming nothing. And, since we [don’t understand it], how do we react? [Some live] like Trump, like frustrated and enraged white men who intend to live forever, seeking solutions in biotechnology, in artificial intelligence, even in the atomic bomb. Because, ultimately, the white man’s civilization would say: “If I die, everyone can die with me. Let there be nothing and no one left.”

Q. What can be done about this?

A. Change the focus. We need to think that, while it’s our biggest problem, old age is also the solution. Old age is absolutely revolutionary if we’re capable of experiencing the process of becoming nothing — of going towards death — as a natural and pleasant process. [We must be] capable of experiencing the fading of our body and mind as an extraordinary event. If we achieve this — if we swap the traditional culture of resignation in the face of death for a new culture of acceptance of becoming nothing — we would take a transcendental step to escape the mass madness in which we are immersed. Now, I very, very much doubt that white civilization is capable of doing that.

Q. Perhaps we cannot conceive of this possibility without leaving behind the paradigm of civilization.

A. Yes, it may be necessary to understand — once and for all — that civilization isn’t a linear and infinite process. It was a long stage in human history and now, it’s grinding to a halt. And so what if it is?

Following the conversation, Berardi asks how long it has lasted. “One hour,” is the reply.

“Well,” he smiles, “I think you have enough crazy things there to write the interview. I just hope it doesn’t take you too many hours of paid work.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.