Maastricht seeks return of valuable prehistoric reptile fossil looted by France in the 18th century

The piece has been exhibited in the Museum of Natural History in Paris since 1795 and is regarded as comparable ‘to what Tutankhamun represents for archaeology’

Maastricht, the southern Dutch city that owes its name to the bridge built there by the Romans to cross the Meuse River, wants to recover an ancient treasure: the fossilized skull of a mosasaur, an aquatic reptile that lived some 66 million years ago when the area surrounding the present-day city was covered by a warm, shallow sea. Discovered at the end of the 18th century, it was looted by French troops and has been on display since 1795 at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Now, the counterpart institution in the Netherlands, the Natural History Museum of Maastricht, which possesses only a plaster replica, wants the Dutch government to officially demand its return from France. The City Council supports the idea and last Thursday a meeting took place at the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science to analyze the case. On the table is a possible restitution comparable to that applied to other historical pieces, whether from the colonial era or World War II.

The official name of this large prehistoric creature is Mosasaurus hoffmanni. It is the first of its kind of the several that have been found in the southern Netherlands, although they have also appeared in other parts of the world. The fossil was discovered in October 1778 in subterranean limestone quarries in the Maastricht area, originating from the remains of shells of marine animals. It dates to the Maastrichtian period (71 to 66 million years ago) of the Late Cretaceous, and was found on land owned by Canon Theodorus Godding. As the limestone mine tunnels where the fossil was extracted were underneath his house, he claimed it as his own. Once in his possession, he put it in a display case so that people could admire it. “Maastricht is in the Catholic part of the Netherlands, and in the Bible there are no dinosaurs or mosasaurs, of course. The one we are dealing with is essential because it represents the first part of what would later become the theory of the evolution of species,” explains John Jagt, curator of paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Maastricht. In his opinion, the fossil is comparable “to what Tutankhamun represents for archaeology.”

In 18th century Maastricht, the reptile’s presence could be explained by alluding to the Flood, but when fossils appeared in other countries, “in a way it was like accepting that God could be fallible; that there was more than one flood. Hence, Mosasaurus led scientists to wonder whether animals and plants could become extinct via natural circumstances,” Jagt continues. Although a complete skeleton has not been discovered, it is believed that the reptile, which measured up to 17 meters (56 feet), had a body covered with scales, a relatively small brain, and a dull tone on its back with a lighter hue on the stomach. Their young were born in the water and had to surface immediately to breathe. How did they become extinct? “Having no predators other than those of their own size or species, they suffered the domino effect of rains of sulfuric acid and other debris that reached the sea after the cataclysm caused by the meteorite impact [in what is now the Yucatán Peninsula] that wiped out the dinosaurs.”

Spoils of war

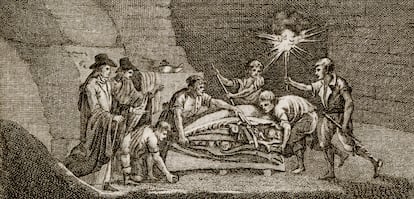

At the end of 1794, Maastricht was captured by the French Revolutionary Army and there was already a precise plan in place to get hold of the fossil. “France had stripped itself of all religious vestiges at that time and they had to get the mosasaur, of great scientific value,” says Jagt. As it was believed to have been hidden somewhere in the city, legend has it that up to 600 bottles of the finest wine were offered as a reward to whoever found it. “That’s all a sham. It was stolen. It was a spoil of war,” Jagt assures. The fossilized skull was taken to Paris in 1794 and declared an item of national heritage. “There is documentary evidence that after Napoleon there was an opportunity for the Dutch to reclaim some of the things that were the product of the rapine of the revolutionaries, and several were recovered. They forgot about the fossil, or maybe they didn’t know about it,” says the curator.

Mosasaurus hoffmanni is part of the Netherlands’ Natural History canon, and the Maastrichtian period is the only division of the geological timescale that comes from the Dutch city. The 175th anniversary of the adoption of the term comes in 2024, and although Jagt prefers not to comment on the possible return of the fossil, he points out that this type of restitution usually affects art. “It’s a decision that is not up to the scientists and many things can happen in the future.” For the time being, the fossilized skull of the Netherlands’ most famous mosasaur rests in a display case in Paris.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.