Kevin Rowland and the thousand lives of the band that only had one hit: ‘I was addicted to cocaine, I lost my house and I had no money’

The English band Dexys Midnight Runners is much more than their indisputable and eternal hit ‘Come On Eileen.’ Unfortunately, no one seemed to notice at the time. EL PAÍS interviewed the founder of the band, which peaked in the early and mid-1980s

After legendary success, countless line-up changes, lots of long breakups, various addictions and bankruptcies, it’s almost a miracle that the band Dexys Midnight Runners (now known simply as “Dexys”) continues to release albums and give live performances.

At the age of 70, Kevin Rowland — the group’s troubled leader, colossal singer and principal composer — is still fighting to remain as the last bastion of the original English group. Although, to be exact — with respect to the original formation — trombonist Jim Paterson also remains in the band.

Formed in Birmingham in 1978, the music that Dexys Midnight Runners put out was classified as “northern soul” (referring to Northern England), even though they rejected this label. Rather, they defined themselves as Celtic soul — part of a struggle defined by Rowland’s debut studio album, Searching for the Young Soul Rebels. The group is best known for its 1982 hit, Come On Eileen.

In 2016, the band released the album Let The Record Show: Dexys Do Irish And Country Soul (2016), and now, Dexys has put out The Feminine Divine (2023), an album in which Rowland dares to deconstruct his masculinity (very much in his own way).

EL PAÍS interviewed the founder of the band on the eve of the only concert that the group will be giving in Spain this year, after the cancellation of part of their European tour and all of their North American tour. “I’ve always felt a lot of anxiety when performing live, but I’ve learned to relax,” Rowland admits, via video call from his home in the London neighborhood of Hackney. “I love when tours go well, but I have a lot of nerves before each show.”

Question. Before The Feminine Mystique, the last album you guys released was seven years ago. And, until now, you hadn’t released a new song in 11 years. Why so long?

Answer. In 2012, we recorded our comeback album, One Day I’m Going To Soar, which we started working on in 2009. From then until 2016, we were very busy, we did quite a few gigs. But in 2017, if I look back, I think I was burned out. We were negotiating with a multinational [music company] and I felt exhausted. I had no enthusiasm or new ideas. I just felt tired. So, I had to solve that problem. And then, around 2021, I thought, “Okay, I think I can compose something now.”

Q. Is The Feminine Divine a love letter to women, a message of apology to them, or both?

A. It’s a lot of things. Those issues are there, but it’s more than that. It’s the story of a man who — in the first song — is a total [tough guy], but in the second song, he realizes that that’s not really him. In the third and fourth, he begins to change and, in the fifth, he analyzes what he’s done to women and sees that he’s been wrong all along. Then, he begins a new relationship, where the woman is the one who guides him.

Q. Are you the man in this song?

A. Well, it’s not completely autobiographical, but there’s definitely something of me in it.

Q. I ask because your new record label — 100% Records — defines the album as “personal, although not strictly autobiographical, which portrays a man whose opinions have evolved over time. Not just about women, but about the whole concept of masculinity that he grew up with.” Could you explain your own evolution?

A. It’s all because of the way I was raised. Nobody talked to me about sex when I was growing up. My parents didn’t tell me anything and, at school, no one explained anything to me. So, when you reach the age of 14 — when your body is exploding with these feelings — it’s still a secret. There’s no one you can talk to about it except your classmates. I didn’t have a guide. I had that desire, but in that strict Irish Catholic environment [in the small city of Wolverhampton] — which was always present — that desire was a bad thing. Nobody told you anything about that. In fact, you weren’t even supposed to feel [desire]. Sex was bad… but you still wanted to do it.

Q. Did you go to a Catholic school?

A. Yeah.

Q. And there was a lot of repression there…

A. Totally. Look, I remember that the nuns, when I was 10-years-old, would start crying in front of me because I was going to go to hell for having stolen something that cost a penny from the store next to the school. They were crying because I was going to hell! That was my education.

Q. I suppose that feeling of guilt marks your entire life.

A. Yes. And especially when it comes to sex. Sex is bad, the people who do it are bad — that was my education about sex and women. It was a big screw-up. The way I was raised, religion and spirituality were on one side and sex was on the opposite side. In fact, they were opposites. They never mentioned sex in church… and if they did, it was in a negative way. So, the idea that sex could somehow be spiritual was a million miles away from me.

Q. In the title track of The Feminine Divine, you sing: “I’ve been thinking about my life / I know that some things I did, they just don’t seem right.” You also say: “This is the only way, the way it has to be / Women have been put down for too long and it’s up to you and me.” We still seem to have many sexist behaviors.

A. It’s true. I’m a work in progress, I’m not a finished product. In my case, it was when I started studying qiqong (one of the martial arts generally practiced for therapeutic purposes) that I connected more with my body and got out of my own head. And I discovered some deep truths about women and my wrong attitude towards them. I used to see sex as a function: something that sometimes needs to be practiced. Once it was over, everything was fine… I didn’t need to do it tomorrow. Until [the process] started again. That’s how I used to feel. Obviously, I’ve had relationships that were more than that, but I didn’t fully appreciate women before.

Q. Until now?

A. Yes, until recently.

Q. And how did that change happen?

A. As I said, I took some qigong courses. I went to Thailand and, the more I connected with my body, the more my eyes opened. In some of these courses, they also mentioned women as goddesses. I thought: “What? They’re not goddesses! They’re just women!” But there came a time when I was knocked on my ass. I said to myself: “Actually, they are. They’re really powerful.” I realized that I — and I think many other men, too – have been afraid of women. That’s why we’ve always tried to control them.

Q. Do you now consider yourself to be a feminist?

A. I don’t know. I don’t even know exactly what that is. I don’t like having to use adjectives. I don’t know what [feminist] means, because it’s a political term and there are many interpretations. But it’s absolutely true that women have been subjugated and feminine energy has been undervalued.

Q. In the video clip for your recent single My Submission, you appear dressed as a woman. Is this a kind of homage to the cover of My Beauty (1999), your second solo album?

A. Some journalists have asked me the same thing, if there’s a connection, but I don’t know. I hadn’t thought about it, because for me, it was something very intuitive. It just seemed like a good idea to dress feminine. I prefer to call it “dressing feminine” than “dressing like a woman.”

Q. Let’s talk a little about the history of Dexys Midnight Runners. What was your goal when you formed the group in 1978?

A. We wanted to do something that sounded fresh. We went back to ‘60s soul as a starting point, because we knew it had the potential to be radical. But we didn’t intend to be a revival. In those years, soul was embodied by the disco sound, but we didn’t fit into that, so we went back to the beginning. Soul is quite raw, simple, honest and direct music. We started listening to those LPs, which were a great place from which to develop our songs.

Q. You never liked being pigeonholed as “northern soul.” Not even in your beginnings, when you guys did a version of Seven Days Too Long, Chuck Woods’ classic.

A. Northern soul (soul music from Northern England) didn’t even exist when all the soul classics came out. Northern soul started in the 1970s, it didn’t exist in the 1960s. I lived in London, from the ages of 11 to 19. At 14 or 15, when I was in high school, I remember buying the Seven Days Too Long single. Also Breakin’ Down The Walls Of Heartache (by The Bandwagon). It must have been 1968 and it was only known as soul, because northern soul didn’t exist. And, to be honest, I never really liked northern soul that much. I just didn’t like their clubs too much. In the 1970s, incredible funk [artists] were coming out: James Brown, War, Fatback Band or Curtis Mayfield. And these northern soul guys were just listening to what had been done a decade before, ignoring the incredible music that was being released at that time.

Q. Do you remember how the name Dexys Midnight Runners came about?

A. Today, many people under the age of 40 don’t know what dexedrine is. We wanted a name that sounded exciting. First, we thought of using All Night Runners, then Midnight Runners. But we decided we needed a word to precede those other two… although we didn’t know what it could be.

One day, when we were having a meeting, [an executive] asked if we had any ideas. Geoff Blythe (the saxophonist) said, “Mandies Midnight Runners!” That name immediately made me think of that drug, because in the 1970s, there were pills called mandies (Mandrax, a central nervous system depressant, similar to barbiturates). It was a fairly pleasant drug, I took it a few times. But we didn’t want a depressant in our name, we wanted a stimulant. So, we opted for Dexys, which came from dexedrine. And we also really liked the way it sounded.

Q. Were amphetamines important in the composition of your early songs?

A. No. Sometimes, as a group, a lot of us would take some speed to go out at night, but I don’t think we ever tried to write anything in that state.

Q. Do you miss those early years?

A. They were very fun, very fun. I remember when we met our manager, Bernard Rhodes. We were just starting out and he came to one of our concerts. We were supposed to record something, because we hadn’t released anything yet. He came up to me and said, “Enjoy this, because it’s the best time.” I thought, “Really? Won’t the best times be when we’re successful?” Years later, though, I understood what he meant.

Q. Was it difficult for you to enjoy your own success?

A. I found it very difficult to enjoy it. I think I was too tense and anxious. I took myself too seriously. Suddenly, I found myself with that pressure, with the expectations of the public, of the record company... it was very difficult for me to manage.

Q. What advice would you give to that young Kevin Rowland?

A. Enjoy it. I never got to enjoy it much. I always had too many problems in my head, I overthought things. I would also advise him to do what he believed was right, to be true to himself. You’ll always encounter people — managers or record labels — who will try to get you to do things that aren’t good for you, but for others. Many people don’t understand that a group can do something their own way: they just want everyone to do it the same way. I remember a former manager telling me, “Every artist worth their salt knows what their marketing should be like.” And he was right.

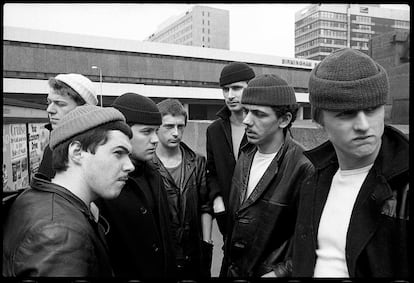

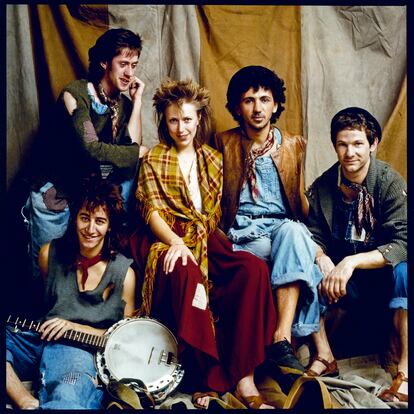

Q. Many people still recognize you guys from your look in the Come On Eileen music video. At the time, the Dexys Midnight Runners looked sort of like chic bums. But you’ve radically changed your image with each album. Why is that?

A. Well, I change my image all the time. Not just with each new album, but even in [my daily life]. I like clothes. I like to dress differently and express myself in different ways. It’s fun.

Q. And what were you all trying to express with that original image?

A. Uff, I don’t remember. 40 years have passed. I guess we wanted to look like a street gang and that was the image of the streets we grew up on. [In those years], all the English bands wore gold suits, so we decided to do the opposite.

Q. The era of the new romantics…

A. Exactly.

Q. After two first albums as popular as Searching For The Young Soul Rebels and Too-Rye-Ay (1982), the third — the fantastic Don’t Stand Me Down (1985) — wasn’t so well received. Was that the biggest disappointment of your career?

A. At that time, it was, yes...

Q. What happened?

A. It wasn’t just one thing. There are many factors for something to be a commercial success. When we released the album, we decided not to release a single. I spoke to the managing director of the company while we were recording it and asked him what he thought of that. And he said to me: “Fantastic idea. We’re going to sell it as a whole album. I think the marketing can work.” But he left the label and, by the time we finished recording, there was a new managing director. And he didn’t think it was such a good idea. He got very [aggressive] on the subject and I had a very big confrontation with him. We almost had to leave the record company. And it took us a long time to finish [the album]... almost three years.

Q. It took too long.

A. Exactly. At most, it should have taken two years. And another issue — which some journalists explained — is that, with the success of the second album and Come On Eileen, we probably lost part of our original fanbase, because they felt it was more like pop music. So, when Don’t Stand Me Down came out, we were stuck in the middle of different audiences. And, on top of that, since we hadn’t released a single, none of our stuff was playing on the radio.

Q. Did you feel misunderstood?

A. Very much so. Because I knew it was a good album.

Q. After that third LP, the group dissolved in 1987. The 1990s were very problematic for you: you were admitted to a detox clinic for your cocaine addiction and you even had to live on social benefits.

A. It was a roller coaster. In the early 1990s, I was fully addicted to cocaine. Things got complicated: I lost my house, I went bankrupt, I racked up debts everywhere… it was a hard time. I couldn’t even pay rent and was squatting in [northwest London].

Q. In 2012, you managed to return to the recording studio with some original members of the group. You released the wonderful One Day I’m Going To Soar — the band’s fourth album. And then, you decided to shorten the band’s name and just call it “Dexys.” Why?

A. We wanted to show that we were the same, but, at the same time, different. We weren’t just a revival band. Also, Dexys Midnight Runners sounds very youthful!

Q. What’s your relationship with Come On Eileen after so much time has passed? Does a singer get tired of their own hits?

A. I’m very grateful for everything it’s given me. I would’ve liked to have another couple of songs as great as that… but I can only be grateful, because it’s helped me a lot.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.