From Beatles lawsuits to the Take That hotline: How band break-ups have traumatized their fans

Zayn Malik quit One Direction and drew distraught reactions. BTS have gone on military service, leaving their career (and their fans) in turmoil. The separation of a group can sometimes be worse than a romantic breakup

In an episode of the animated adult series Metalocalypse (2006), based on the fictional death metal band Dethklok, a newsreel reported a mass suicide of fans after the group, for the umpteenth time, postponed the release of their new album. In another episode, hundreds of fans traveled to the Arctic Circle to witness a one-song gig having signed a waiver of liability for their possible death during the show. This is a parody of the world of heavy metal and of the most radical fans. However, the most dedicated followers can be found in higher concentrations in communities of teenagers who are more fascinated by the boy band of the moment than the worshipers of any satanic group or those devoted to Viking nostalgia. At least, when it comes to extreme reactions to a band definitively hanging up their guitars, microphone or keyboard with playback button.

While there is a tendency towards longevity in heavy metal, as evidenced by the lengthy careers of long-running bands like Iron Maiden and Judas Priest, a 70-year-old fan will probably be more sympathetic than angry when their idols leave the stage due to the ailments of old age. The story changes when it comes to short-lived groups defined by their youthfulness. These are boys and girls in the very prime of their lives, engulfed by massive teenage success. For them, singing well and being good-looking becomes a curse they must escape from, even if it means leaving behind millions of fans shattered by existential emptiness, who had pledged their undying love and loyalty all too quickly. “What happens has much to do with the fear of losing your youth, because something expires, it is lost forever,” believes Argentine psychoanalyst Morella Mor, who applies her research to the world of music. “Bands speak about our lack of love, about the injustices we experience, sometimes they give voice to feelings that we can’t express when we are teenagers. They can be a very strong symbolic prosthesis.”

“There are loads of groups of friends that form because you socialize around a music group. A whole life can be formed through that bond,” she adds. For Mor, a fan mourning the dissolution of a band or, in extreme cases, the unexpected death of an idol, must ask themselves “what happened or what was missing in your life that made you decide to put a celebrity in such a highly important place as someone you love, as if it were a sister, a parent or a close friend.” And we should also be grateful that this group, with which we have had such a deep connection, ever came into existence: “If a group of people want to go to the same place, if individual desires converge at the same point and hold together over time, it is a miracle, an alchemy that requires a great deal of willpower.” Now, try explaining that to all those heartbroken fans.

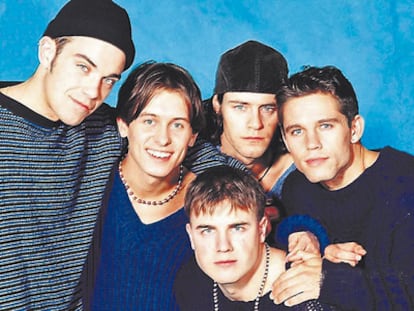

Take That

Take That, commercially the biggest band at the time, had announced its breakup in February. “Unfortunately, the rumors are true. How Deep Is Your Love will be our last single together and Greatest Hits will be our last album,” Gary Barlow solemnly said at a press conference. A year earlier, Robbie Williams had made the decision to quit the group due to a deteriorating relationship with his bandmates, and also because of his addictions.

In a staple of Spanish contemporary television culture, several fans awaited the group’s arrival at the Madrid airport for a final performance in 1996. Between garbled information about the door through which they would exit, erroneous data and races up and down the terminal, the hours went by and there was no sign of the band.

“When I found out they were splitting up I said I was going to kill myself because I was having such a bad time. We’ve been prepared to do anything and we’d give everything for them,” one of the teenage girls in the crowd told a reporter. “One day in class I picked up the lid of my pen, started scratching until I drew blood and made their symbol,” another said. One of the mothers present urged people to stop worrying about it, explaining that “at their age I was crazy about the Beatles,” in a call for calm, which she herself broke shortly after when she defined them as “a load of bastards” for not showing up. The reporter’s lack of understanding of the teenage girls’ screams was met with the eloquence of another female, who told her: “They’re so handsome, can’t you see that?” Asked about Take That’s breakup, one outraged fan bemoaned claims that fan pressure has taken its toll on the group and asks, “Don’t we have the right to love them?” while another candidly described the tragedy as “a real bitch.”

In the U.K., the charity Samaritans even provided a telephone hotline for Take That fans affected by their breakup. Those who, past their youth, kept faith in a comeback got rewarded. A decade later, the group reformed and even Robbie Williams made a timely appearance for a tour and a new album release. The new album with the full quintet, Progress (2011), broke the record for copies sold in a single day.

The Spice Girls

Last May marked the 25th anniversary of Geri Halliwell’s departure from the Spice Girls and, with it, the beginning of the end of a band that stood at the pinnacle of success. By the end of 1997, they had released Spiceworld: The Movie, the other Christmas blockbuster in the year of Titanic. The former featured cameos by all the celebrities of the era and almost didn’t feature the then-Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair (Halliwell’s statements describing Margaret Thatcher as “the first Spice Girl”, an assertion denied years later by Mel C, may have weighed heavily). They inspired passions around the globe: South Africa’s President Nelson Mandela, an anti-apartheid hero who spent 27 years in prison, called the Spice Girls’ visit to the country “one of the greatest moments” of his life.

According to pollster The Voting Booth, Halliwell’s walkout was the biggest news story of the year for the majority of Brits. The group continued to tour and even achieved another number one, but the scale of their success dwindled. In his article, When the Spice Girls broke up, I realized friendship does actually end, journalist Christopher Luu explained why the group no longer made any sense to their fans: “Part of that feeling of loss had to do with the band’s marketing. Fans identified with a single member of the holy altar of Spice. But for everyone that saw the Spice Girls as a quintet, losing any part of the group felt like a betrayal.” Although they did not officially break up, the Spice Girls went on a long hiatus and have since reunited in full for only one tour — between 2007 and 2008 — and a performance at the 2012 London Olympics. After that, it was not just Halliwell, but Victoria Beckham who wanted out. Luu, who compared the breakup of the Spice Girls to when a group of firends split up due to reasons beyond their control, said of those reunion: “We all learned that friendships could endure a breakup or two.”

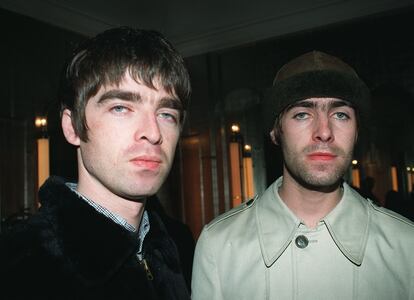

Oasis

Few people took the breakup of Oasis seriously in the middle of the Rock en Seine festival in France in the summer of 2009. Neither did the man who broke the news, Bloc Party frontman Kele Okereke. “Oasis have cancelled. That’s a shame, isn’t it guys? I’d like to dedicate this next song to anyone who really wanted to see those inbred twins,” said the musician jubilantly from the stage, in reference to the Gallaghers, while his guitarist mockingly played the chords of Wonderwall. Okereke had previously been on the end of it. You’re nobody in music if you haven’t been on The Simpsons or been insulted by Liam or Noel, and Bloc Party had received that honor years before, when the former said of them: “I don’t give a fuck about them, I don’t like them, they’re like a university band.” Among the audience, the issue was greeted with more resignation than sadness. The fact that Oasis canceled a concert was nothing new (they had just done so five days earlier due to the singer’s alleged laryngitis, although his brother Noel later revealed that what he had was a hangover), or that the turbulent Britpop duo had a falling out, as apparently happened that night.

14 years later, everything indicates that it was for real. Even Liam Gallagher took a while to get used to the idea: “I’m beginning to think Noel doesn’t like me,” he reflectively told ICON in 2019. With fans sharing custody of each brother’s solo careers (and the occasional crumbs of Oasis they deliver at their concerts, which are more plentiful at Liam’s than Noel’s) and in constant bickering over who is the bad Gallagher and who is the victim, the reunion rumors have been as constant as the denials. “I don’t care about Oasis fans,” Noel Gallagher told EL PAÍS before his performance at the fourth edition of the Mad Cool festival, in an interview in which he assured that only “taxi drivers” asked him about the group getting back together. Liam has fed speculation by publicly calling for the return of Oasis on several occasions. However, the only success he has had has amounted to several hundred thousand retweets and the disappointment of fans who greet each apparent reunion with the same laughter with which they received their breakup. Neither the 25th anniversary of the groups’ most impacting albums, Definitely Maybe (1994) and (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? (1995), nor the historic treble achieved by Manchester City — the football team both Gallaghers are supporters of —, have so far managed to pull off the assuredly lucrative return.

The Beatles

The Beatles invented everything, including “the concept of breaking up a group,” as Rolling Stone magazine put it in an article describing how “the ugliness” surrounding the end of the Liverpool band “set the tone for every breakup from that point on.” The trauma of the Beatles’ dissolution in 1970, 53 years ago, was so severe that the reasons for it are still being debated today. With the members becoming increasingly estranged and focused on their individual artistic interests, as the documentary series The Beatles: Get Back (2021) illustrated, the distribution of blame is as complex as it was for their fans around the globe to assume that the group would not be continuing. “Ringo, John, George and Paul are alive, well and at peace. The world keeps on turning, and we and you with it. When the rotation stops, it will be time to worry. Not before,” wrote Apple publicist Derek Taylor, unsuccessfully hoping to quell the tears.

The fall of the Beatles empire had all the ingredients. There were lawsuits, nasty comments, different versions of the story and even eccentric proposals (George Harrison, who left the Beatles during the Let it be sessions and later returned, was almost replaced by Eric Clapton). The death of the band’s manager Brian Epstein in 1967 had upset the balance of power in the group, with Paul McCartney gradually assuming leadership and attempting to control something that had become uncontrollable. McCartney, the other remaining living Beatle Ringo Starr, still has to mitigate the hatred towards Yoko Ono, Lennon’s partner, and deny that she was responsible for the breakup of the band. This belief has led to the typical misogynist imagery when it comes to interpreting the tragic endings of different music groups (see what some Nirvana fans think of Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain’s fall from grace). Not to mention those who believe that the reason is that Paul McCartney has been dead since 1966.

One Direction

One of the most alarming phenomena of modern fandom took place in 2015 following Zayn Malik’s departure from One Direction, which prompted the hashtag #CutForZayn encouraging female fans to self-harm in anger over the artist’s exit. Various disturbing images and messages of suicidal tendencies appeared on different social media channels. However, the 4Chan forum and its incel subculture, where the hashtag #CutForBieber had originated years ago after the leak of some images of Justin Bieber under the effects of marijuana, played an important role in the spread of the trend. The real danger of what for some was a joke (in the minds of some, inducing suicide seems to be one) led different media outlets and specialists to follow the events closely.

Beyond the scandalous, the end of One Direction unfolded as one might expect — coming a few months after Malik’s departure. Parallels were drawn with the end of Take That, and of course with that of the Beatles (the outgoing member’s then fiancée, Perrie Edwards, was likened to Yoko Ono). There were also back-and-forth comments, as fans took to Twitter on their individual journeys from denial to anger and, finally, to acceptance that “pause” was a clear euphemism for “break-up.” Malik’s departure also prompted some to mourn his absence by organizing candlelight vigils.

BTS

It seems that BTS are not simply having a hiatus like One Direction, but their break comes down to circumstances beyond their control. In 2022, the group announced that it was hitting the stop button. Although they cited fatigue and a desire to pursue their solo careers, as well as to develop on a personal level, the ultimate reason seemed to stem from the members’ compulsory military service in South Korea. BTS are expected to reunite in 2025, when all of them have fulfilled their duty (at the moment, of the seven, J-Hope and Jin are already underway and they will be joined by Suga imminently). The fact that no one raised a question sparked the biggest anti-militarist movement and call to insubordination in history, given the power of Army, the name of the fanbase. The likes of Donald Trump, who experienced the boycotting of his 2020 electoral campaign rally resulting from a movement on social media, and Spanish TV presenter Pablo Motos, who faced a barrage of criticism last January when he compared J-Hope’s appearance to that of former El Hormiguero host Flipy, can attest to the organizational capacity of the group’s fans.

In a community characterized by positivity and good feelings, BTS fans took the announcement well and, instead of expressing their disapproval, they showered their social media accounts with words of thanks, encouragement and promises that they would wait for as long as they needed to. Since it is never wise to err on the side of caution, South Korea’s defense minister announced that he would not prevent BTS from performing while in military service should they wish to do so.

Extremoduro

Far away from the standards set by the boy bands, the end of Extremoduro turned out to be much more turbulent than expected for their fans as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic. In 2019, six years after the last album and with frontman Robe Iniesta focusing on his solo career, the group announced its separation and a farewell tour around Spain. The Spanish rock band smashed the record for ticket sales in just 24 hours in the country, reaching 200,000. But the tour never took place. As the health crisis exploded, the dates were postponed periodically until they were left in the uncertain limbo that worried their numerous audiences, especially due to the lack of announcements. To add fuel to the fire, Robe, tired of waiting, released a new solo album and announced that he was going on tour on his own.

From that point on, the unrest grew. A statement by the vocalist on Extremoduro’s official website, published without the knowledge of his bandmates, suggested that the group’s tour would not take place because it was pointless and he expressed his wish for the promoter Live Nation to return the money to the fans for the tickets. Guitarist Iñaki Uoho Antón responded with another announcement on his Facebook account, disassociating himself from Iniesta’s words and insisting on his intention to go ahead with the tour. Finally, in August 2021, the promoter announced the decision to cancel the tour “as a result of Robe Iniesta’s refusal,” in a statement in which they expressed “their astonishment at the persistent obsession” from the singer to “cast doubt over the return of tickets,” accusing him of “slipping away without returning the advanced payments in his possession.” Fans and band members were outraged, and Robe and Live Nation were involved in a lawsuit (for which the promoter is claiming, according to the Extremoduro frontman, €3 million). It seems that everyone, both on and off stage, lost the desire for the proposed tour to take place. “If you were excited about playing with a band, you wouldn’t quit,” Iniesta fittingly said in an interview last year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.