How the Levi’s 501 jeans became a cultural artifact: ‘The design is perfect… it’s not a response to any other type of style’

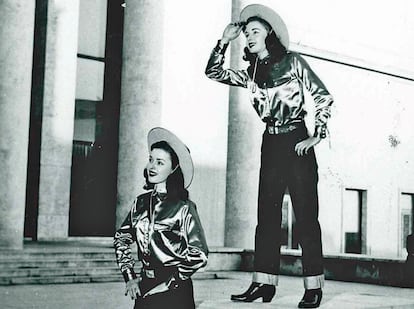

The garment just turned 150 years old. This is how the clothing company works and innovates at their San Francisco headquarters, with an ever-changing take on the cowboy style

The first woman who dared to wear jeans on a daily basis wasn’t a celebrity of her time. Nor was she engaged in farm work. Her name was Viola Longacre: she was an English teacher. In the early-1930s, she decided to wear her Levi’s 501 jeans while studying at California State University, Fresno. Her name was engraved on the lining of the pocket.

In 2017, a vintage collector found them at an auction and gave them to Levi’s. “We contacted her granddaughter, Bette, who told us her story. Although she was married, Viola was an independent woman who worked and traveled as much as she could during her youth. [The 501 jeans] are a rare model, with the cloth label instead of the leather one. There are also fewer metal rivets – it was a cheaper make, because it was the time of the Great Depression,” explains Tracey Panek, Levi’s director of heritage.

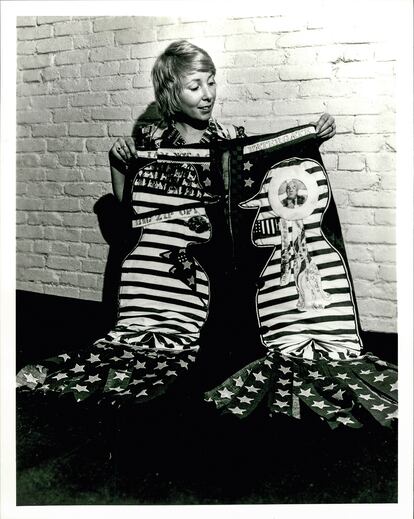

That first pair of female-worn jeans are now called Viola Jeans: they were part of the exhibition that Levi’s put together this past May at the San Francisco Armory, on the 150th anniversary of the 501s. In addition to Viola’s pair, there were models on display which were once owned by Steve Jobs, Harvey Milk, Patti Smith or Sally Ride – the first American woman to travel into space – along with handfuls of anonymous people who, without knowing it, were making history.

Panek – a historian by training – has spent more than a decade making visits to museums and auctions, while spending hours on social media trying to find the personal stories that accompany Levi’s cowboy-style jeans. One of her favorites is that of Avtandil Lomsadze – a Georgian who, in the late 1970s, traded in the family cow for a pair of 501s. “At that time Levi’s symbolized freedom and rebellion in Soviet regions. They were difficult to get; they cost a small fortune,” Panek explains. “That trade made this young man a legend in his town; it was a friend of one of his relatives who wrote to tell us about it.”

You could trace a kind of social history of the 20th century based on who wore 501s and where they were worn. It’s been a century-and-a-half since the first lot of studded denim pants were created by Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss. At Levi’s headquarters in San Francisco, it’s clear to everyone that a pair of 501 jeans isn’t a piece of fashion, but rather, a cultural artifact. “Any new design is really just a review of some moment in history,” explains Paul O’Neill, the director of design for the collections.

This Irishman – an expert in vintage style – doesn’t sketch ideas every season. For the last 15 years, he’s been diving into an archive of more than 20,000 units, rescuing historical pieces and reproducing them. “There’s no clear criteria that we use to rescue one model or another,” he notes. “Sometimes, [it’s like] the 50th anniversary of the ‘summer of love,” or we first create a story to tell. Then, we search in the archive for a specific time that has something to do with that story. I still haven’t discovered everything in it.”

O’Neill began collecting Levi’s jeans as a teenager. “I was already collecting vinyl… music led me to clothes,” he says. Over the years, he’s realized that his Levi’s are the only thing about his outfit that never changed.

“If I look at photos of my father, I can tell when they were taken [based on] the clothes he was wearing. But even I couldn’t tell what year the picture is from if I only looked at his jeans,” he jokes, pointing to the first 501 model – from 1873 – displayed inside a showcase. With an adjustable belt loop, button-up suspenders, a single back pocket and wide legs (they were meant to be worn over everyday clothes), the design could have been created the day before yesterday. O’Neill has now reproduced this first model in a limited-edition collection. “We’ve done it exhaustively, with every imperfection. When we reproduce an old model, we don’t change anything. It’s fascinating to see how, for example, when we take [advertising] campaign photos with a contemporary approach, that [old pair of jeans] continues to work.”

“Actually, the design is already perfect; it’s not a response to any type of fashion. It’s been evolving for a century-and-a-half, [becoming] as practical and resistant as possible. Today, [what’s different] is that each element – each small detail – is more ecological,” explains Paul Dillinger, the head of Global Product Innovation at Levi Strauss & Co.

This former designer became disenchanted with the production model of the firms he worked for before Levi’s. “They had the same manufacturing process, the same cost-cutting [methods],” he sighs. He began teaching pattern-making classes in fashion schools. “When [Levi’s] called me, they allowed me to combine both jobs. In the end, it’s about researching how things are made and valuing them.”

Since joining Levi’s in 2010, Dillinger has experimented with biodegradable fabrics (from hemp to cellulose), with dyes created from bacteria and – above all – “with a more sensible idea of consumption. It’s very difficult to balance a big brand’s production with a message against overconsumption, but it’s possible. We handle the only product that’s not only durable, but it gets better the older it gets. This is why it’s important to educate the public on how to take care of their jeans, or to [make them aware] that they can always be repaired”, he explains.

All the innovations that Levi’s implements are available to other competing brands that wish to carry them out. A little over a decade ago, the comapny inaugurated Eureka – an innovation center open to anyone with a good idea to improve the efficiency of the product. This is how, for example, Levi’s discovered and opted for the ozone washing machines from the Spanish company Jeanología, which has enabled the jean manufacturer to reduce water consumption by more than 90%. Later, in 2018, Levi’s created the FLX project – a laser system that produces the finish without the need for chemicals. With futuristic machinery at the service of centuries-old patterns, technology is being applied to the only consumer object that has never gone out of style.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.