Eye in the sky: How news helicopters have created a new television genre in Los Angeles

Over 900 police chases of fleeing criminals each year make for a popular offering on city TV programming

Fifteen minutes of fame was not enough for Johnny Anchondo. Local television devoted some 100 minutes of live coverage to this repeat offender, following one of the wildest chases Los Angeles has seen in recent years. In that time, the 33-year-old criminal ran a stop sign and caused an immense mobilization of the police as he stole two pickup trucks, rammed into dozens of vehicles at high speed and escaped from at least 15 patrol cars that were hot on his trail for some 12 miles. All of this was recorded by the all-seeing eye in the sky, news helicopters.

“Chases are the best. They are dynamic, they move fast. Things can change in an instant. Sometimes they seem endless from up there,” says Stu Mundel, one of the journalists who have been following events on the city streets from a helicopter for decades. “And I say this from the bottom of my heart, it’s genuine, but I always wish things would end well,” he adds.

In Los Angeles, chases are now a television genre in their own right. Journalists like Mundel fly for hours over a gigantic urban sprawl of 88 cities with 11 million people. From way up high, they report on traffic, crashes, shootings and fires in the metropolitan area. But few events arouse the audience’s interest as much as the chases through the city’s vast thoroughfares. The police chase starring Anchondo attests to that fact; the video has over 28 million views on YouTube.

The genre was born in this city. The idea came to John Silva, an engineer for a local television station, while he was driving his car on a freeway near Hollywood. “How can we beat the competition?” he wondered. The answer came to him behind the wheel. “If we could build a mobile news unit in a helicopter, we could beat them in arriving to the scene, avoiding traffic and getting all the stories before the competition,” Silva told the Television Academy in a 2002 interview.

In July 1958, a Bell 47G-2 helicopter made the first test trip for the KTLA network, becoming the first of its kind anywhere in the world. By September of that year, Silva’s creation, known as the Telecopter, already had a special segment on the channel’s news program. Before long, every major television network had one. Silva died in 2012, but his invention transformed television forever.

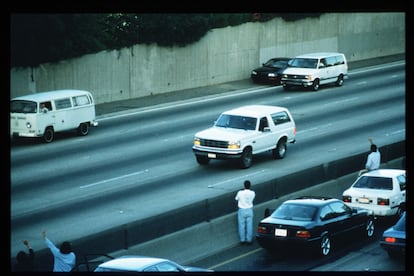

The chase genre’s crowning moment came in June 1994, when the Los Angeles police chase of a white Ford Bronco was broadcast live on television. In the back of the vehicle was O.J. Simpson, the former football star, whom the authorities had named the prime suspect in the murder of his ex-wife and her friend. Bob Tur (now known as Zoey Tur after a sex change operation), the pilot of a CBS helicopter, located the van on the 405 freeway being followed by dozens of patrol cars. Within minutes, there were so many helicopters following the convoy that Tur found the scene worthy of Apocalypse Now. The audience was such that TV stations interrupted the broadcast of Game 5 of the NBA Finals to follow the chase, which lasted two hours.

“It’s a very interesting thing. It may sound morbid, but it’s not. People follow [police chases] because they are like a movie, we want to know how it will end and how the story unfolds: will good triumph over evil? Or will this person manage to escape? We journalists are objective, but the adrenaline and excitement is genuine,” says Mundel. In his years of experience, he has seen how technology has evolved. In the 1990s, people used a paper map as a guide. Today, viewers can see a map superimposed on the images Mundel captures with his camera.

Four out of 10 chases are initiated after a vehicle is stolen. The second most common reason for them are hit-and-runs by drivers who are drunk or under the influence of drugs. According to the Los Angeles Police Department, most fugitives are hiding a more serious crime: homicide, rape or violent robbery. In 1998, only four out of the 350-plus drivers arrested after a chase were let off with only a traffic ticket; five hundred chases were recorded that year.

A growing phenomenon

In 2022, 971 chases were recorded. On average, chases last about 5.34 minutes and cover about five miles, although the vast majority (72%) end within five minutes and do not travel more than two miles. Thirty-five percent of documented chases ended in crashes with injuries or fatalities in 2022. That figure represents a slight decrease from 990 in 2021. In 2019, there were fewer: 651 chases and 260 crashes.

A few decades ago, authorities tried to reassure Angelenos by claiming that a person had a one in four million chance of accidentally being killed in a police chase of a criminal. “There’s a better chance of being struck by lightning,” the police department estimated. But things have changed. An official report presented in April indicates that, over the past five years, 25% of chases have left people dead or injured. That almost always includes the suspect, but the number of innocent people who have been hurt has also increased.

Although there is plenty of material on the street, uncertain times for local journalism have limited coverage. Univision and Telemundo have dispensed with their helicopters in Los Angeles. Fox and CBS have joined forces and are using one aircraft instead of two. For the time being, KTLA, which invented the genre, remains committed to having a helicopter in the air.

The days may be numbered for these televised events. Some metro police departments have asked their officers to stop chasing criminals at high speed for the safety of the public. Instead, they have employed technology with high-definition cameras and drones to chase criminals, as has happened in cities like Dallas, Philadelphia and Phoenix.

The Los Angeles police have said that they are studying the implementation of the Star Chase system in some of their vehicles. Star Chase features a launcher that triggers a GPS transmitter, tagging a fleeing vehicle and allowing the authorities to track the position of the person who has escaped in real time. Another measure under consideration is the use of an industrial-strength nylon net that traps the rear axle of the fleeing car. All of this could yield dramatic footage for the eye in the sky.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.