The great escape from Nazism in the Alps

Research by the Hohenems Jewish Museum reconstructs the flight of thousands of refugees from the Third Reich on the Austria-Switzerland border

In the turbulent 1930s, the musician Willy Geber had a good reputation in Vienna for his schlager, a light musical genre revered by the Nazi regime, except when the musician was Jewish. One of his hits was a foxtrot titled America, you have it better. After the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, he was forced to flee and chose to sneak across the Vorarlberg, on the Alpine border with Switzerland. He escaped with the help of an SS squadron, whose enthusiasm for robbery was greater than their anti-Semitic ideology — they would go out hunting for Jewish refugees, rob them, and then expel them from the country. It was August 16, 1938. As soon as he arrived in Switzerland, Geber wrote a letter to his wife with more than a hint of sarcasm: “When it got dark, we walked for about two hours and were divided into two groups. The SS told us that they would now take us to the border and deal with our conduct later. We were in an open field. At that moment, an SS man delivered a speech in which he asked us not to engage in spreading rumors about atrocities. The Führer does not approve of aggression, etc. And he told us the path we should follow....”

In the Swiss city of St. Gallen, Geber founded the KKK schlager band. Shortly thereafter he managed to emigrate to the U.S., where ironically he did not fare much better. The catchy melodies of his compositions, underscored with love lyrics in German, had little success. He had to trade the piano for work in supermarkets and died in poverty in 1969.

Thousands of refugees tried to reach Switzerland between 1938 and 1945 by crossing the border via the Alpine Rhine, as this section of the river that flows into Lake Constance is known. From Jews sentenced by Nazism like Geber, to political opponents of the Third Reich, homosexuals, deserters, prisoners of war and forced laborers from occupied Europe. Hanno Loewy, director of the Jewish Museum in Hohenems, in the Austrian state of Vorarlberg, estimates that there were about 15,000. “In the summer of 1938, Switzerland closed its borders to refugees and turned its back on the Jews fleeing Nazism: they were poor, they came with nothing, the country was not interested in supporting them. They had been robbed, like Geber, who was lucky. Paradoxically, the SS saved his life, although for them that was the least of it. They just wanted to expel him.”

Loewy began the research a decade ago. The result is the book Über die Grenze (“Crossing the border,” Bucher Verlag), which brings together 52 refugee stories. But above all it is a monumental 100-kilometer cycling route that starts on the shores of Lake Constance and follows the course of the Rhine into the heart of the Central Alps. And there is a digital element: at the exact place where each story took place, a monolith has been erected which narrates the escape attempts, thanks to a QR code. The historians’ border layout can be followed (in English and German) at crossing-the-border.

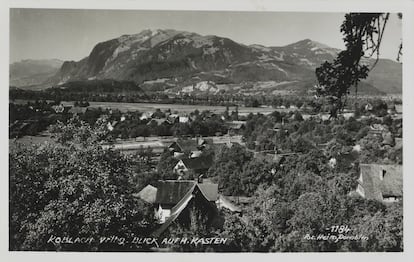

One of those responsible for the project, Raphael Einetter, highlights the case of the idealist Bohumil Snižek and his odyssey from Chrast, deep within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. He cycled 240 kilometers (149 miles) to Pilsen, continued on foot and by train to Munich, finally reached the Rhine at Koblach and swam across under fire from the border patrol. In Switzerland he could smell “freshly brewed coffee, freshly baked bread from the bakery.” He was arrested, but managed to make contact with his initial target in Geneva: the liaison in the European resistance of the Czechoslovak government in exile. He was sent to Marseilles, and from there he crossed the Pyrenees with nine other Czech resistance fighters: they all ended up in the Model Prison in Barcelona, from where they were transferred to the concentration camp of Miranda de Ebro.

As the newly inaugurated Franco dictatorship was playing the neutrality card, it handed Snižek over to the British Government in Gibraltar, which transferred him as a lieutenant of the Czechoslovak Armored Brigade to the Allied siege of Dunkirk, which began in September 1944. For three years he had traveled across Europe and through fascism in the thick of World War II. He managed to return to Prague, where the Soviet occupation awaited him.

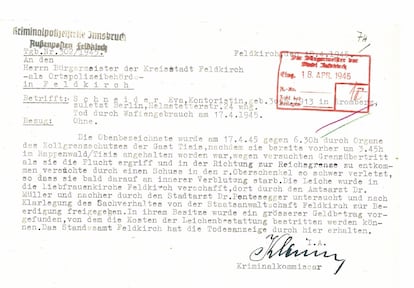

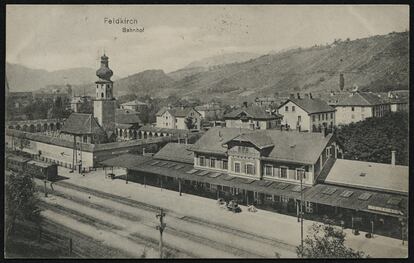

There are tragic cases such as that of the journalist Hilda Monte, pseudonym of Hilde Meisel, a Viennese Jewish socialist who fought in the resistance against the Nazi regime. On the BBC in 1942, while in exile in London, she broadcast a shocking report on the beginning of the mass extermination of Jews in occupied Poland. In April 1945 she was hunted in one of her illegal raids on the Third Reich. Held at the customs office in Feldkirch, a stone’s throw from Liechtenstein, she was fatally shot when she tried to escape in the early hours of the morning. Just two weeks later, French troops entered and World War II ended in the alpine Rhine valley.

More than stories of successful escapes, the dramatic escape attempts of ordinary people stand out. Five Jewish women from Berlin’s intellectual circle planned their escape near Hohenems, taking advantage of the proximity of the Diepoldsau natural pool to the border fence on one of the Rhine’s meanders. They chose the night of May 7, 1942. Paula Hammerschlag committed suicide by overdosing on Phanodorm after suffering a mental breakdown caused by her arrest. Marie Winter was murdered in the Maly Trostinek extermination camp in Belarus, and Gertrud and Clara Kantorowicz did not survive the Terezín concentration camp. Only Paula Korn managed to escape to Switzerland by jumping over barbed wire amid shrapnel blasts from border guards.

For Hanno Loewy, research does not only reveal the past. “Seen from the Swiss perspective, it is very topical. The treatment of refugees today is reflected in some of the stories we tell. And it reminds us of where hatred and media agitation against the foreigner takes us.”

On January 7, 1943, customs agents in Feldkirch stopped a freight train from Slovakia that looked suspicious. Fourteen Jews were hidden half-buried in the mountains of coal transported by the wagons. By that time, 58,000 Slovak Jews had already been deported to Auschwitz and Majdanek. One of the faces blackened by the coal was that of Gittel Balbirer, a 17-year-old Polish girl who had lost her parents in the Belzec extermination camp and her older sister shot to death while fleeing from the SS. She had two other siblings, Basia, 15, and Mendel, 20, who hid on the following train. Gittel was deported to Auschwitz on March 3. Basia and Mendel were transported in May and managed to survive Auschwitz and the death marches until their liberation by Allied troops, but they never saw their sister again.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.