Federico García Lorca, the musician: How the poet elevated flamenco and Spanish folklore

A less well-known side of the genius from Granada is his musical talent. He was a great pianist and connoisseur of Andalusian music, whose status he raised with his vision and poetic rhetoric

Federico García Lorca’s genius is so great that, more than a century later, he still resonates in popular culture with the force of rough seas. It doesn’t run out. On the contrary, it keeps growing. There is the genius of Lorca the poet, author of Poema del cante jondo (Poem of the Deep Song), Gypsy Ballads and Poet in New York. There is the genius of the playwright who penned Blood Wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba. However, little has been said about the genius of the musician and compiler of folklore. Or, at least, this side of Lorca does not stand out as much compared with his unbeatable and influential lyrical and theatrical work.

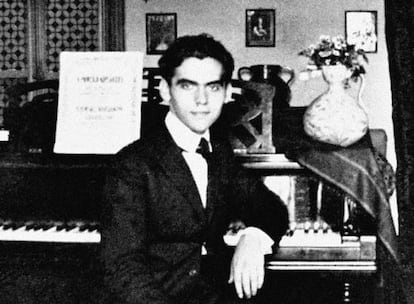

Yet it should be remembered that before being a poet, Lorca was a musician. “First of all, I am a musician,” he once said in an interview. “I’m crazy about songs,” he said in another. His musical training came before any other, but above all, his passion for music palpitated at an early age and marked his entire life, including his conception of poetry. The musicality of Lorca’s lyrics was his hallmark, as can already be seen in some of his early books, such as First Songs and Songs. These contain short compositions that correspond in many cases to poetic structures of popular songs. The elements of folk music run through his poetry and find their maximum splendor in Gypsy Ballads and Poema del cante jondo.

Lorca was always grateful to one of his great teachers, Antonio Segura. This pianist from Granada was his piano teacher when the Lorca family moved from Fuente Vaqueros to Granada. According to the poet, Segura was the one who introduced him to “folkloric science.” Lorca, who deeply admired Beethoven, had extraordinary musical skills, that is to say, a magnificent ear and a wonderful technique at the piano. Thanks to Segura and his own instinct, from a very young age he developed a love of the folklore that he imbibed from the wet nurses who were part of the household and who told him stories and sang lullabies. From all this, Lorca emerged a wonderfully musical being — to the point that at the Madrid Student Residence he captivated everyone when he played the piano, even more so than with his poems.

To talk about Lorca is, therefore, also to talk about music. These days, this link can be seen in a stupendous play, Federico García, directed and performed by Pep Tosar at Teatro Pavón in Madrid. The production evidences that the best way to explain Lorca is by using narrative elements such as flamenco guitars, singing and dancing. He was the poet of rhythm and of the duende, the spark that illuminates music. The string of musical admirers who have drawn on Lorca for their creations is long and seemingly endless: Camarón de la Isla, Paco de Lucía, Enrique Morente, Lole and Manuel, Carlos Cano, Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith, Ben Sidran, Ana Belén, Lagartija Nick, Los Planetas… And yet, the point is not to underscore that unbreakable relationship between Lorca and music, but to highlight his musical universe, his contribution to Spanish popular music.

Lorca also had another teacher and friend in Manuel de Falla. His meeting with the famous composer in 1920 marked him deeply. He was fascinated by Falla and learned more about cante jondo (regarded as a pure form of flamenco vocal style) and about Andalusian folklore in general. With Falla, he held the Cante Jondo Competition in Granada, an event that had the virtue of elevating cante jondo and, in general, all Andalusian popular music, to an indisputable cultural category far removed from the clichés. This competition is now historic and remains of incalculable value for flamenco. In the case of Falla, who was the main promoter of the competition, the influence of cante jondo began with his ballet composition El amor brujo (1914-1915) and continued in his later works, such as the Concerto, the Fantasía Bética (1919) or The Altarpiece of Maese Pedro (1923). For the competition, Falla published a brochure with his own theory of cante jondo in which he affirmed that “primitivism” and “orientalism” were cultural currents of the cante jondo and recognized their influence on contemporary composers from other nations such as Russia (Rimsky-Kórsakov, Aleksandr Borodin, Mili Balakirev and Mikhail Glinka) or France, with Claude Debussy as the standard-bearer.

Lorca took note of Falla’s wisdom and took his theories further in three fantastic lectures: Architecture of Cante Jondo, Spanish Lullabies and Game and Theory of the Duende. There is a little book containing these three conferences on music called Donde se hiela el tiempo (Where time freezes), which underscores how the artist from Granada was a great connoisseur of Andalusian music, which he elevated by developing a radically poetic prose to talk about duende and folklore. In fact, he defined duende better than anyone else. And as the poet Jorge Guillén pointed out: “The memory of Lorca is the richest treasure of Andalusian popular song.”

Lorca may have been a musical theorist and a walking repository of musical history, but he was also a respected musician who was personally in charge of many of the musical selections that accompanied his productions with the university theater group La Barraca. In fact, when he was in New York in 1929, he wowed everyone when he played the piano at parties in Harlem. His fascination for “all things Black” also came from the glorious age of jazz and because he found human ties and similar artistic impulses among two marginalized groups, that is, between Gypsies and Black people. On a personal level, the poet also felt this marginalization due to his condition as a homosexual man. In New York, Lorca went to the Cotton Club and understood that jazz had a lot to do with flamenco, that duende and swing were linked: either you have it or you don’t, and you can’t explain it.

Perhaps the most important work to emerge as a result of so much musical passion and knowledge was Canciones populares españolas, a series of Spanish folk songs. In this recording, released in 1931 by the La Voz de su Amo label, Lorca teamed up with the flamenco dancer and singer Encarnación López Júlvez known by her stage name La Argentinita. The record contains songs with arrangements by Lorca, in some cases with contributions by composer friends of his. These recordings, which include Anda jaleo, Nana de Sevilla and En el café de Chinitas, convey a glorious flavor of life on the streets, the seedier side of town and the café nightlife of the period.

If the fascists hadn’t shot him in 1936, it would have been great to see how far Lorca could have gone with his musical talent and passion. Luckily for art, the name of Federico García Lorca continues to shine today. He is a universal poet and playwright. And we must add: a universal musician.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.