Forty years on from ‘Paris, Texas’: Wim Wenders tells the story of the making of his masterpiece about the West and sadness

The German director won the Palme d’Or at Cannes for his movie—written by Sam Shepard and starring Harry Dean Stanton and Nastassja Kinski—about heartbreak and starting life over again

German director Wim Wenders is fascinated by the classic American cinema of John Ford, Nicholas Ray, Howard Hawks and Samuel Fuller, and filming in the United States was a dream come true. The 77-year-old, Düsseldorf-born director did just that at the end of the 1970s, after he had already made a name for himself as an auteur of interest in European cinema. However, dreams come true in some very strange ways: Wenders accepted Francis Ford Coppola’s proposal to direct Hammett, a screenplay in which the mystery writer Dashiell Hammett himself became the star of a noir thriller. Warner Brothers ultimately destroyed that movie in 1982, to the dismay of Coppola and Wenders--”I dedicated years of my life, I moved there just for a hellish outcome,” Wenders said. But the film was essential for the German director’s decision that he would only direct again if he had absolute freedom and without a previously closed script. Thus, in the spring of 1983, he set out to shoot a film in southwest Texas that a year later won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and struck a chord with audiences around the world. Forty years ago this spring, Wenders began filming Paris, Texas.

Two weeks ago, Wenders visited the BCN Sant Jordi festival in Barcelona. There, the director spoke about his career to a group of students from the Faculty of Communication and International Relations of the Ramon Llull-Blanquerna University. He imparted some dialectical gems, such as his suggestion to shoot without a script, if possible (”I recommend that to everyone: shoot with a friendly scriptwriter by your side, and the result will be impressive”), his view that “experience is overrated and that it is better to shoot as soon as you arrive on location (”Let your film show your discovery, your path”).

Wenders also reflected on the fame of Paris, Texas. “It’s a strange phenomenon. Sometimes there are films that are released at exactly the right time, and that happened with Paris, Texas. I don’t know if it’s luck or fate, or the combination of those who create it. In my case, Harry Dean Stanton was [there] at the perfect time; Nastassja Kinski was at the peak of her career; it was Sam Shepard’s first script, and Ry Cooder wanted to prove himself. All I could do was not screw it up,” he said.

After the disaster that was Hamnett, Wenders returned to Europe, and shot The State of Things in Portugal with Samuel Fuller, whom he admired. He now had the freedom he craved for his career, which had been stolen from him in Hollywood. “But I wanted to shoot in the West, in those immense landscapes. It was and still is clear to me that you can’t make movies by themes, that they can only come from the characters. And if anyone knew those landscapes and those characters, it was Sam Shepard. Sam was always writing about the West. His book Motel Chronicles was the essence of Paris, Texas. In the book On Location: Cities of the World in Film, Wenders himself notes that “a street, a facade, a mountain, a bridge… or a river are not just the backgrounds of the narrative. Each has its own history, its own personality, an identity that deserves to be taken into consideration.” Paris, Texas reflects that philosophy, and Wenders captured the mythology of the American West—created by Shepard—through his own European perspective (with the added bonus of cinematography by Dutchman Robby Müller) and personal admiration. “Maybe [that’s] because I’ve never been interested in the history of cinema, but [rather] in the history of the people who have made films,” the director said.

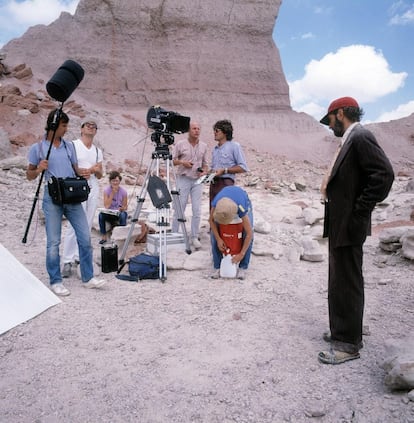

The story opens with the appearance of a man, Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), in the Texas desert. He comes out of nowhere; he hasn’t been heard from for four years. His return to civilization is also a personal resurrection and a recovery of his family. Wenders filmed the opening sequence in an area called Devil’s Graveyard, at the recommendation of an old helicopter pilot who was hired for the shoot. Curiously, producer Anatole Dauman –the film was a Franco-German co-production– decided not to shoot in the Paris of the original title, and, instead, they shot in other nearby locations such as Marathon - where Travis is picked up by his brother Walt (Dean Stockwell) – and in a score of houses in the middle of nowhere. “From there, on the way from both [places] to Los Angeles, we went through Ford Stanton, a town of about 2,000 people, and El Paso, [which is] quite a bit bigger, because we wanted to show all [the different] types and sizes of American towns,” recalls Wenders. They shot not only in Los Angeles, but in another big city, Houston, which Wenders liked better. “And we discovered the Camelot gas station, where Walt stops to refuel before meeting his brother again, by chance and filmed there because the name tickled our fancy.”

Wenders’ initial plan was geographically more ambitious: he wanted to go to California and up to Alaska. Shepard objected. “He told me, ‘Don’t bother with that zigzagging. You can find all of America in one state: Texas.” As Wenders explained, “Having the answers is very different from shooting to seek those answers; I’m all for that. Like Truffaut, who didn’t differentiate between his life and his films.” But in Paris, Texas the ending was clear. Subconsciously, Shepard, Wenders and co-screenwriter L. M. Kit Carson were on the same page; they knew how they were going to get to Travis’ dramatic speech to his wife, Jane (Nastassja Kinski), who works in a peep show.

Where did that famous monologue come from? Shepard had gone on to other pursuits, and there was no text for that moment. Years ago, L. M. Kit Carson wrote: “Wim called Sam and told him what he wanted, how they had come to this meeting. Shepard wrote it down, dictated it over the phone to the [secretary], she typed it up, and Harry Dean went nuts. Sam told him from a distance, ‘Just say the words. It’s all there.’ They shot all day, cutting nonstop, and he only did it in one go at the end of the day.”

Wenders enjoys the process of shooting films—discovering the soul of the locations when he arrives—but he believes that films are made in the editing. “Editing is like simmering; it’s my favorite part of production.” Of the Paris, Texas filming, he recalls Harry Dean Stanton’s insecurity first and foremost. “For many months, I was his therapist. He looked ugly, [he was] old and a bad actor. He was 35 years older than Nastassja. He filmed nervously, undervaluing himself every day. When we finally went to the Cannes festival, I told him that I could no longer be at his beck and call, and to take someone to accompany him. Harry paid for a young actor to go on the trip, and he stood by his side hour after hour, relentlessly supporting him. That young man was Sean Penn.”

The Paris, Texas soundtrack by Ry Cooder, who was little known at the time but is a star today, was also an enormous success. A few years ago, in an interview with EL PAÍS, Wenders explained: “I had wanted to hire him for Hamnett, but he had just released his first album and the studios turned him down. I promised him that, as soon as I could, I would sign him. I did. Paris, Texas would not have achieved the success it did without Ry’s music. Harry Dean was a good musician and a great singer. He liked to perform Mexican songs. On the set at night, he would sing them for us in the bar. One day Harry asked me if I didn’t think the film needed a song like that, and I thought it was a brilliant idea. So, he did a version of Canción Mixteca (Mixtec Song),” and we recorded it at the end of the production. Once the film was released, Ry went on tour. At his first three concerts in Europe, Harry—who had paid his own way—showed up to play with him. For the fourth one, Ry called me and asked me to do something. ‘He’s threatening to follow me around for the whole tour, and he’s an endearing guy, but he just thinks he’s part of the show.’ It finally stopped when Ry traveled all the way to Japan.”

Paris, Texas didn’t make it to the Oscars. Wenders is clear about the reason for that: “Twentieth Century Fox bought it [for circulation] in the United States. They prepared a smart release, they even thought about winning [Academy Awards]. Suddenly, the management at the top changed, and within three weeks even the receptionists were different. The new executives wanted nothing to do with the ideas of the previous ones, and they didn’t even prepare a screening for the members of the Academy or made an announcement. Harry was heartbroken. Instead, months earlier, in May 1984, he won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. “I had already been there in 1975 for Kings of the Road, [when I was] too young to enjoy it. [In] 1984, I experienced it differently. At the end of the competition, we were asked to stay because we had won something. As the ceremony went on, we still hadn’t won an award, and at the end only John Huston [for Under the Volcano] and I were left. We looked at each other and smiled, even though we didn’t know each other. They announced my name and I said, ‘Sorry, John, it’s me.’ It turned out that Huston was later awarded a Palm for his career. We had a good laugh afterwards.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.