Pink snow tints the edges of Antarctica

Microscopic red algae, responsible for a phenomenon also known as watermelon snow or blood snow, are proliferating due to global warming and in turn accelerating it

In Antarctica, there is a small peak rising to 275 meters (900 feet) and named Mount Reina Sofia, after the queen emerita of Spain. On this sunny February morning, its white slopes seem as if a massacre has taken place here. “That’s the pink snow!” exclaims the biologist José Ignacio García, making himself heard amid the cries of Antarctic terns, territorial birds that attack the intruders. Also known as watermelon snow or blood snow, this phenomenon is striking, beautiful even, yet alarming: microalgae, favored by climate change, are proliferating on the snow and turning it red. The immaculate white of Antarctica reflects almost all of the sunlight and returns it to space, but the growing pink surface absorbs more heat, accelerating melting. Warming generates more pink snow. And pink snow generates more warming.

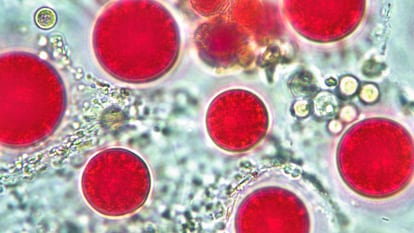

García bends down to pick up a sample, which looks like a watermelon slushie. The algae that covers Mount Reina Sofía in patches is Sanguina nivaloides, a species first described in 2019. The meaning of its scientific name in Latin is eloquent: blood in the snow. Each creature has a single cell, about 20 thousandths of a millimeter in size, with a molecule inside that gives it its characteristic red color: astaxanthin, made up of 40 carbon atoms, 52 hydrogen atoms, and 4 oxygen atoms (C₄₀H₅₂O₄). “It’s the same pigment that produces the color of salmon,” explains García, from the University of the Basque Country in northern Spain. The synthetic version is the dye E161j, used in cosmetics and the food industry. A milliliter of melted snow contains thousands of algae.

The blood snow is nothing new, as the Greek philosopher Aristotle noted more than 2,300 years ago in his History of Animals. “Even in substances that seem less corruptible, living beings are born, as, for example, in old snow. Snow turns red after a certain time,” he noted. The phenomenon, however, is now worrying the scientific community, especially in Antarctica. Mount Queen Sophia rises on remote Livingston Island, off the Antarctic Peninsula, the portion of the continent closest to South America. It is one of the regions most affected by climate change. Global temperatures have risen by an average of 1.1 degrees compared to pre-industrial levels, but here the increase has exceeded 3 degrees in just half a century.

A study by the Chilean Antarctic Institute estimated four years ago that tiny algae cause the melting of more than two million tons of snow on the Antarctic Peninsula every southern summer. Lead author Raúl Cordero, a climatologist, warns that this estimate, based on 2018 data, is already outdated. “This figure could be much higher,” he warns in an email. “Although the algae are natural, their excessive proliferation is not.”

The biologist José Ignacio García and his colleague Beatriz Fernández are leading a Spanish project that is beginning to study pink snow in this corner of Antarctica. In recent years, numerous scientific groups have turned their attention to algal blooms in polar regions and in high mountain areas. It’s not just the watermelon blood; snow patches of other colors are also emerging, caused by other types of algae. A team of Scottish researchers has just published their results on the neighboring Antarctic island of Robert: 20% of the analyzed surface was covered by various microalgae, with a dark purple hue generated by the species Ancylonema nordenskioeldii.

The phenomenon is even visible from space. In 2019, a group from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom) detected, using satellite images, nearly 1,700 green algae blooms on the Antarctic Peninsula, covering a total of two square kilometers. The statement issued at the time by the British institution was forceful: “Climate change will cause the coast of Antarctica to turn green.” Climatologist Raúl Cordero emphasizes that the study only identified intense patches visible to the naked eye. His own team was at the Chilean Yelcho base on the Antarctic Peninsula in February, perfecting a technique to use drones to detect relatively low concentrations of microalgae. “We believe their presence is much more abundant,” he warns.

The team from the University of the Basque Country, whose other members are the biochemist Irati Arzac and the chemist Enara Alday, hiked to the summit of Mount Reina Sofía to collect samples of pink snow and to set up an experiment with mosses. From the summit, the sheer size of Livingston Island, covered in colossal ice, can be sensed. This is a legendary place. A Spanish warship with a crew of 644 disappeared in 1819 while sailing around Cape Horn en route to Peru. Some artifacts found on the coast of Livingston Island in the 19th century suggest that those sailors were, unwittingly, the first people to set foot in Antarctica, although they did not live to tell the tale. At Christmas 1986, four members of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) chose this island to establish the first Spanish Antarctic base, Juan Carlos I, funded by the Ministry of Science. That’s why the neighboring mountain is called Reina Sofía.

The biologist Beatriz Fernández scans the horizon from the summit. Antarctica is larger than Europe, she explains, but there are only two native plants: the Antarctic carnation and Antarctic grass. Ancient ice covers 98% of the continent. “Antarctica is the coldest continent on the planet, but even more important for making life here difficult is the fact that it’s a desert. What little fresh water there is is almost always frozen,” says Fernández. Microalgae proliferate in the increasingly abundant coastal areas with temperatures well above zero during the southern hemisphere summer. American glaciologist Chad Greene of NASA summed it up with a resounding phrase: “The edges of Antarctica are crumbling like a cookie.”

An international team of scientists issued a call for action on February 6 in the journal Science. The researchers—led by the biogeographer Luis R. Pertierra of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid—warned that much is known about penguins and seals, but very little about the rest of Antarctic life, such as microalgae and other microorganisms, which hinders our understanding of the continent’s ecological processes. The authors, including biologist Antonio Quesada, head of the Spanish Polar Committee, urged research into these unknown creatures, capable of triggering phenomena as disturbing as blood snow.

The astrophysicist Kike Díez, from the University of Oviedo, has participated in the discovery of more than 50 exoplanets, worlds orbiting stars other than the Sun. In Antarctica, his mission is more risky. Tethered to the high-altitude guides Iñaki Zuza and Josito Fernández to avoid falling down a crevasse, he explores the glaciers of Livingston Island to precisely measure the albedo, the technical term for the percentage of sunlight reflected off a surface.

Diez carries two cumbersome radiometers in his backpack: one measures the solar radiation arriving from the sky and the other one calculates the amount of reflected light that bounces off the ground. The percentage of reflected light depends on the state of the snow and its impurities, including microalgae. The blood snow reduces albedo by 20%, according to previous studies. Green snow reduces it by up to 40%. “It’s a feedback loop effect,” the astrophysicist laments. “As the Earth’s temperature rises, expanses of ice like this one retreat. So, the Earth’s ability to reflect incident light diminishes, and the temperature rises. And these expanses keep retreating. It’s a vicious circle,” he warns.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.