Welcome to the Revolution, with all its blood, sweat and tears

Historian Enzo Traverso’s book is a cultural and intellectual examination of 19th- and 20th- century revolutions. Here is an A-Z of the highlights

Since the 1789 storming of the Bastille during the French Revolution, populist uprisings have either been mythologized or demonized. The socialist collapse in the late 20th century has relegated such revolutions to the horror section of the library. Italian author Enzo Traverso’s Revolution: An Intellectual History (2021) reinterprets and rehabilitates the history of 19th- and 20th-century revolutions by avoiding unmerited idealization and revisionism. Traverso traces the cultural impact of these violent uprisings and calls them milestones of modern history.

Traverso is a renowned scholar of European intellectual history and the author of numerous works such as Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory (2017). His book on revolutions is an eclectic constellation of dialectical images a la Walter Benjamin that is so diverse, it challenges the reader to sort through all the revolutionary chaos. We accepted that challenge and offer the following guide to his ideas and anecdotes.

Anonymous. This is the essence of revolution: anonymous masses capable of uniting, self-organizing, and becoming an unstoppable force. This is the romantic aspect of revolutions that has captivated so many intellectuals — transformation from the bottom up.

Bogdanov. The USSR dreamed of creating a new man: homo sovieticus. Nothing was impossible, and the remarkable Aleksandr Bogdanov took this literally. His utopianism soared in science fiction novels that described communist societies on Mars enjoying eternal youth thanks to regular blood transfusions. In 1926, Bogdanov even persuaded the Soviet government to set up a blood transfusion institute with him in charge. According to Enzo Traverso, Bogdanov died from a tainted blood transfusion. Bogdanov believed resurrection was possible, but so far there are no signs of his return.

Celestial. Heaven will be stormed and conquered, according to the Marxist canon. But the Winter Palace surrendered peacefully — there was nothing epic about it. That’s why Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein had to conjure up a more dramatic scene for October (1928), his film about the 1917 October Revolution. An attempt to portray the truth with a lie.

Donoso. There is a Spanish link between classic counterrevolution and modern fascism, and his name is Juan María Donoso Cortés (1809-1853). A philosopher, essayist, statesman and 19th-century apocalyptic visionary, he saw revolutions as a societal disease. It made no difference whether the cure was dictatorship or violence, the important thing was to eradicate the disease. Carl Schmidt called Donoso “the most radical of the counterrevolutionaries, an extreme reactionary and a conservative of almost medieval fanaticism.”

Excluded. They were always excluded. The Jacobin Convention outlawed all women’s clubs in 1793. Any excuse would do, including the medical community’s opinion that genital location (internal in women, external in men) determined an individual’s public role — women should stay indoors while men should lead public lives. Traverso sums up this type of thinking by saying, “Human rights were really just men’s rights.” Notable exceptions like Rosa Luxemburg, Dolores Ibárruri (La Pasionaria), Angelica Balabanoff and Ruth Fischer weren’t enough to bring the gender issue to the fore. But one woman succeeded — Claude Cahun. She was the lesbian daughter of French bourgeois parents who became a surrealist photographer, sculptor, and writer, defender of queer identity, dissident Marxist, secular Jew, and resistance activist. Traverso believes Cahun possessed a pure revolutionary spirit.

Fresco. In 1932, Mexican artist Diego Rivera was commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller to add a mural to the soaring lobby of Rockefeller Center in New York City. Before it was even finished, Rockefeller fired Rivera and destroyed Man at the Crossroads. But Rivera avenged the ignominy when the Mexican government gave him free hand to create another fresco for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. And so the Sistine Chapel of the Mexican Revolution was illuminated by Man, Controller of the Universe. The revolution is on full display in IMAX format: the epic battles, the masses, the conflict, the repression and the future.

Guillotine. Surrounded by a frenzied mob, the guillotine awaited Louis XVI. Drums rolled and the blade dropped, severing the royal head. The executioner held it up for all to see, and the crowd shouted, “Long live the Republic!”

H-hour. Revolution is the locomotive of history, said Karl Marx. The metaphor came to represent the crucial role of the railroad in the expansion of capitalism and the proletarianization of the peasantry. But something was missing. For the trains to run properly, schedules had to be synchronized because clocks fluctuated from one area to another. As railways expanded, Greenwich Mean Time was established in 1884 and became the planet’s official clock. The capitalist economy demanded punctuality. Perhaps that is why Joseph Conrad wrote The Secret Agent (1907), a novel about an anarchist plot to bomb the Greenwich Observatory (UK) and blow up time.

Iconoclasm. Vladimir Lenin was emphatic — the bourgeois state could not be transformed. It had to be vanquished with violence and then reinvented. But only the first part of Lenin’s formula is remembered — destructive rage — just like the firing squads that shot up religious icons in churches during the Spanish Civil War. Sometimes fear is the message.

Juvenile. This is the undercurrent that runs throughout the Traverso’s book and almost all of its protagonists: revolution is for the young.

Karakozov. Dmitry Karakozov specialized in killing kings and statesmen, a type of “propaganda in action.” His bloodthirsty revolutionary deed was truly anarchist reductionism.

Lukács. The role of intellectuals in the vanguard of revolutions is a prominent theme in Traverso’s book. One anecdote, true or not, will suffice. In 1956, when Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to put down the uprising, a Red Army officer asked Georg Lukács to hand over his gun. The old revolutionary-philosopher held out his pen.

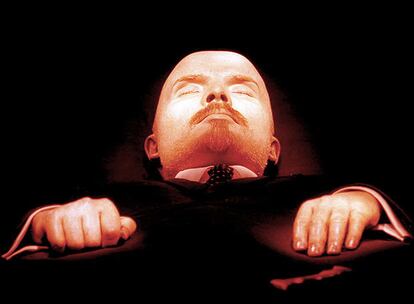

Mummy. Lenin’s widow said no, and Trotsky and Bukharin were appalled at the idea. Mummify Lenin like some sort of Orthodox saint? They were atheists, after all. Nonetheless, a physical body made up of 23% of Lenin’s actual corpse was fabricated and placed on permanent display. As it says in “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,” the epic poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky, “Lenin and life are comrades / Lenin lived / Lenin lives / Lenin will live.”

Nechayev. The author of the radical manifesto Catechism of a Revolutionary (1869), Sergey Nechayev believed every revolutionary had a moral and political responsibility to destroy the civilized order in its entirety. Leave nothing intact. For the revolutionary, there is only one joy — the success of the revolution. “Day and night, he must have only one thought, one goal: merciless destruction.”

Ñangotarse. In Central America, the word means humiliation, submission, and it seemed to be the destiny of the colonized. For Frantz Fanon, the revolutionary author of The Wretched of the Earth (1961), the oppressed had to rise up at all costs and free themselves from violence using violence.

Orgasm. In 1917, the Great October Socialist Revolution in the Soviet Union changed everything. Even in the bedroom, said revolutionary women like Alexandra Kollontai, a Soviet ideologue who espoused a new ideal for women and denounced the unequal sexual morality of the times. Social liberation meant sexual liberation for all, including women. Socialist happiness meant “satisfying orgasms.”

Pariahs. This is how high society viewed the revolutionary intellectuals of the 19th century. Alexis de Tocqueville, the paradigm of the counterrevolutionary aristocracy, describes the first time he saw Auguste Blanqui, leader of the Paris Commune’s far-left faction. “He had bloodless and emaciated cheeks, white lips, a sickly, wicked and repulsive expression, a dirty pallor, the appearance of a moldy corpse… He seemed to have spent his life in a sewer from which he had just emerged.”

Quid. “Revolutions tell us about the past, but perhaps they also foretell the future,” writes Traverso. This is the central thesis of his book.

Razor. Hundreds of thousands of Spanish women aligned with the losing Republican side during the Spanish Civil War had their heads forcibly shaved. Their Republican sins were inscribed on their heads, a visible symbol of the new Francoist order. But this crude insult was also used by the other side. Traverso describes how in newly liberated Italian and French cities after 1945, women accused of “horizontal collaboration” with the Nazis and Fascists were taken to the central square and had their heads shaved in front of jeering crowds.

Symbol. La Marseillaise is an epic revolutionary anthem, written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle while he was in hiding after fighting for the Paris Commune. Traverso describes the lyrics as messianic, finding a fair dose of religion in the revolutionary sentiment of France’s national anthem.

Tatter. A red tattered cloth, a rag — nothing more. It was used by royal authorities to execute the sans-culottes — the lower classes during the French Revolution. But the common people appropriated the red rag, and it came to symbolize the color of revolutions since 1848.

Utopia. It has a cruel ending: disappointment. Emma Goldman and her companion, anarchist Alexander Berkman experienced it while living in the USSR. In The Bolshevik Myth (1922), Berkman bitterly wrote, “One by one, the embers of hope have been extinguished. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the revolution have been renounced… The revolution is dead, its spirit weeps in the desert.”

Violence. Mao summed it up: “A revolution is not a dinner party.” Traverso explicitly acknowledges this stark fact: “Violence is in its genes.”

Walter Benjamin. The German philosopher is the leading light of Traverso’s book who illuminates everything with one idea — revolutions are leaps into the future in which the past reappears, in which memory flashes.

X. An X marks a crossroads. It was 1968, when a constellation of revolutionary events shook the world. Traverso writes about those events: “The revolution had to be anti-capitalist in the West, anti-Stalinist in the East and anti-imperialist in the South.” Everything came together in 1968: the barricades in Paris, the Prague Spring and the Tet offensive in Vietnam.

Yearning. Revolutions usually begin momentously and end in tragedy. That is why Traverso writes, “Their memory is steeped in mourning” for their martyrs, a yearning counterweight to the narrative of power.

Zombies. The fall of the Berlin Wall shattered the socialist utopia. But because Traverso refuses to let it die, he writes, “The left of the 21st century must reinvent and distance itself from previous patterns. It must create new models, new ideas and a new utopian imagination.” This is how revolutions are born.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.