Cannabis or spinach? Behind Popeye’s century-old legend

In the 1930s, as the government waged a battle on marijuana, the sailor became one of the most beloved characters in the United States

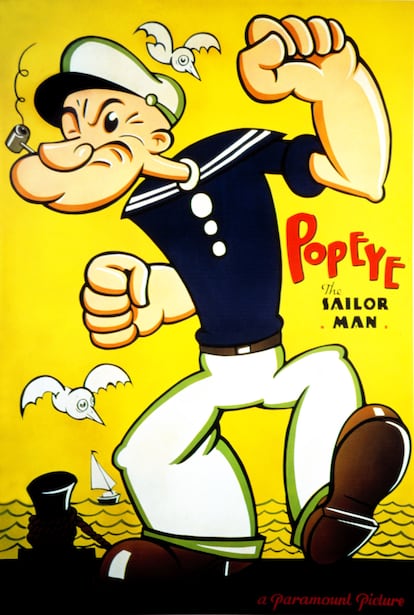

When on December 19, 1919, the first Thimble Theatre comic strip appeared in the New York Evening Journal, one of the circulars owned by William Randolph Hearst, no one, not even its author, cartoonist Elzie Crisler Segar, could have predicted what was to come. The strip focused on the humble Oyl family: Olive, her eccentric brother Castor, her fiancé Ham Gravy and her parents Nana and Cole. The melodrama-tinged satire didn’t enjoy great success at first. But everything changed on January 17, 1929, when Segar introduced a minor character who would go onto eclipse the initial cast: a mysterious sailor with hypertrophied forearms, one missing eye and a corncob pipe perpetually stuck in his mouth. His name was Popeye.

The character appeared when Castor and Ham Gravy hired him to sail a ship. His appearance was brief: the cartoonist had no qualms about killing him off. But after fans insisted, Segar resurrected the seafaring immigrant a few months later. Despite his crude, womanizing ways, the public fell in love with the character’s authenticity and his broken English. In an era marked by the absence of real-life heroes, Popeye won over working-class families immediately.

“He was born in the interwar period and at the beginning of the Great Depression, a really difficult time that has some parallels to the present. Society needed to distract itself from the miseries of everyday life. He and the rest of the characters found clever ways to keep going, with strength and courage. They were survivors,” says Andrés Pérez, who between 2013 and 2019 translated Segar’s strips, and those of his successors Bud Sagendorf and Bobby London, into Spanish. “Magical realism was invented in Latin America,” he adds, “but in my opinion, there’s a clear precedent in the comic.”

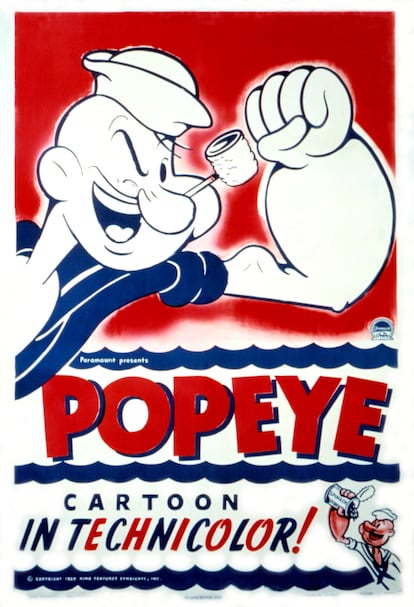

Little by little, Popeye took over Thimble Theater. Segar got rid of a few characters and incorporated new ones. Ham Gravy left the scene in May 1930 after Olive fell in love with the intrepid sailor. In addition to the daily black-and-white strips and Sunday color comics, Popeye became a pop icon thanks to the animated shorts that the Fleischer brothers began producing for movie theaters in 1933. He, Mickey Mouse and Betty Boop, in that order, became the decade’s most beloved cartoon characters.

As a result of his popularity, in the second half of the 1930s, consumption of spinach increased by 33% in the United States. By then, it was known that the German scientist Emil von Wolff had made an error when analyzing the leafy green’s iron content in 1870: he left out a comma, writing down that 100 grams contained 35 milligrams of the mineral instead of 3.5. What was confirmed in 1929, coinciding with Popeye’s debut in Thimble Theatre, is that spinach was rich in vitamin K, which helps prevent osteoporosis and reinforces muscles and joints.

Segar knew that. But contrary to popular belief, Popeye didn’t always use the vegetable to fight his opponents. “The first mention of spinach appeared in a strip published on June 26, 1931. And he doesn’t eat them to get instant strength: he consumes them in other contexts, because he’s already strong, and, as one strip says, they help him maintain a healthy diet. When the Fleischers introduced spinach in the shorts in 1933 to accelerate the action, Segar began using spinach occasionally, without giving it much importance. The same thing happened with Bluto, later known as Brutus: Segar drew him once in 1932, and the Fleischers made him Popeye’s arch-enemy,” Pérez explains.

In 1938, at the peak of Popeye’s popularity, Segar died from leukemia in Santa Monica, California. Other cartoonists took on his legacy, continuing to draw the series, bringing it all the way to today’s Sunday strips drawn by Randy Milholland

The rereading of a classic

The 1930s weren’t defined only by the depression, food shortages and unemployment. In the US, once prohibition was repealed in December 1933, the country’s political agenda found a new enemy: cannabis. “For centuries, hemp had been used to make candles, sailing ropes and sailors’ clothing. After 1930, however, the interests of various lobbies began to demonize the plant in order to prevent competition with the nylon, wood, petroleum and pharmaceutical industries. The psychotropic substance was an excuse to eliminate it,” explains Ana Rodríguez, manager of the Barcelona Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum.

Harry Anslinger, director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, led the crusade. “His discourse was tremendously racist, and he used his relationship with Hearst to spread an anti-cannabis campaign in the press,” Rodríguez says. “Everything from it giving you superpowers and making you bulletproof, to sensationalist stories that defined smokers as criminals and sexual predators. At the same time, in that context, propaganda films like Reefer Madness, in 1936, and Assassin of Youth, in 1937, appeared, seeking to teach parents about the dangers of marijuana.” Anslinger’s strategy worked: on August 2, 1937, Congress approved the Marihuana Tax Act, a law that imposed fines of up to $2,000 and prison sentences of up to five years for anyone who consumed, imported or prescribed cannabis. In practice, it meant prohibition.

What does that have to do with Popeye? For some time, a rumor has circulated online that Segar used spinach as an allegory for cannabis. In 2005, an article titled “What’s in Popeye’s Pipe?” written by Canadian cannabis activist Dana Larsen, went viral. The author argues that the character’s name gives a clear clue to his habits. The explanation is much simpler: in the 1920s, American sailors used the term to refer to people with one eye.

The Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum has on display a toy figure of the sailor from 1935. “On guided tours, we say that it’s a hypothesis, not a fact. The creator of Popeye never wrote it down, so it’s impossible to corroborate it. What’s true is that, in that period, ‘spinach’ was a common slang term for marijuana. Songs like Hooray for Spinach!, by Skinny Ennis and his Orchestra, or The Spinach Song (I Didn’t Like It The First Time) by Julia Lee and Her Boy Friends, adopted the term to avoid censorship,” Rodríguez points out. “Both refer to it because of Popeye’s success,” she adds. “There’s no record of any song before 1933 in which spinach is associated with cannabis.”

“I know Segar’s work inside out, and I can confirm that all the conjecture in the article is false,” Pérez, the translator, says. “There is one vignette, published March 29, 1931, in which Popeye himself explicitly says that he smokes tobacco. Larsen also recounts that the cartoonist signed the strips with the drawing of a cigarette or cigar, but that was his personal emblem since the beginning of Thimble Theater. And about him sucking the spinach through his pipe, he started to do that in the 1950s in the animated shorts, not in the comic, and under specific circumstances: for example, when he was tied up and only could use his head. If you analyze it well, the text is full of inconsistencies.”

“Segar wouldn’t have found the insinuations funny. Although, if he were alive, with time he would have taken it as a joke. He was a man with an excellent sense of humor,” Pérez adds. “It’s clear that the character has been twisted, so what I would say to people is to go back to the original strips. Popeye is one of the greats, like Citizen Kane was for film.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.