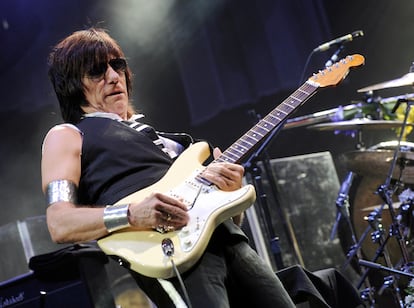

Jeff Beck, the most unusual of guitar heroes

The British musician – who passed away on January 10 – was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on two occasions, in 1992 and 2009

They called it “the Surrey Delta” – a reference to the celebrated Mississippi Delta, the birthplace of African-American blues. Indeed, in the British county of Surrey – right next to the London metropolitan area – three of the defining guitarists of English rock were born at the end of World War II: Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton.

When they grew up, the three men formed the group known as The Yardbirds. Of the band members, Beck – who died this past Tuesday, January 10 – was known as the most imaginative and, possibly, the most gifted in technical terms as a guitarist.

Beck’s original sound was astonishing: he played with the tension of the strings, approaching Indian or Arabic sounds. He integrated feedback effects and pounded the vibrato lever, all while exploring the pedals. Without looking, you could tell it was him from the moment he started playing, but it was impossible to know how his tunes would end. His fellow guitarists listened to him with their mouths open: it was a shock. He was often referred to as “a guitarist’s guitarist.”

This raises an uncomfortable question: how could Beck have only achieved a fraction of the success achieved by his two contemporaries? He had an infinitely richer musical palette than Clapton, who rarely strayed from blues. Page was almost as eclectic as the recently deceased, but he became too commercial.

Maybe his lack of wealth came from the fact that he never tried too hard. It’s not untrue to say that Beck was far more passionate about vintage cars than he was about his Fender guitars. A memorable episode from his life was in 1969, when he decided that he wouldn’t perform at the Woodstock Festival – he didn’t feel like travelling up into the mountains of New York, claiming many years that he hated “hippies.” Clearly, being in sync with the culture of the times was never his priority.

Beck’s first two LPs – Truth (1968) and Beck-Ola (1969) – were recorded very quickly and with too many fillers. His laziness was in stark contrast to Page’s iron will and shrewd adaptation to the market, which demanded long concerts and lots of calm material for FM radio. While rockers such as Led Zeppelin toured every key corner of the United States, Beck locked himself in his auto shop. He was also constantly being hospitalized, due to racing accidents.

A late-comer to the rock boom, Beck had the very bold idea of joining the Motown label headquarters with the Funk Brothers, the instrumentalists of the celebrated “Detroit sound” – something that no other rocker attempted. Unfortunately, he didn’t understand the peculiarities of those musicians. He never found his way around the studio – the recordings have never been released.

Beck’s laziness kept him tied to music producer Mickie Most, who wasn’t in tune with modern sensibilities. Most made Beck record merengues, such as Love is Blue – a Eurovision hit – modernizing the instrumental version of the orchestra by Paul Mauriat. But this kind of work didn’t have lasting power among the general public.

It is true that Beck later tried his luck with more ambitious producers, such as Steve Cropper, George Martin, Ken Scott and Jan Hammer. These collaborations worked well in the short-term, but they lacked long-term vision. Some scoffed that his prodigious gifts were being wasted.

For even the most famous musicians, Beck was considered to be quite intimidating. The members of Pink Floyd thought of him to replace Syd Barrett, but they didn’t dare propose the idea to the legend. Something similar happened with the Rolling Stones – in the end, Mick Jagger only managed to get Beck’s lightning guitar skills for his solo albums.

Little by little, though, people in the music industry understood that he wasn’t an ogre. He used to join jam sessions and attend charity concerts of all kinds as a guest.

After trying to remake the Jeff Beck Group – which he had formed after The Yardbirds split up – he leaned towards the fusion of jazz-rock. This greatly impressed his colleagues – he began to accumulate Grammy Awards in the category of instrumental rock. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on two occasions: as a member of The Yardbirds in 1992 and as a solo artist in 2009.

In time, he settled into the role of musical virtuoso: skinny as a scarecrow, coolly arrogant, hair dyed like a raven’s wing: the relentless idol of fearful musicians. Until the end of his life, he indulged the staff of music clubs by singing Nessun dorma – “Let no one sleep,” from the final act of Puccini’s opera Turandot – Over the Rainbow, or A Day in the Life by The Beatles.

This humorous side must have surely frustrated those who were expecting to see glimpses of his mid-1960s psychedelia. But when the curtains closed on Jeff Beck, Surrey was a long way away.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.